Abstract

The residual peels of andiroba seeds were submitted to alkaline pretreatment that aimed to maximize the recovery of fermented sugar. Evaluation of the best operation performance via the reaction time variables (20, 60, and 100 min), NaOH concentration (2, 3, and 4% (m/v)), and temperature (60, 90, and 120 °C) at a fixed solids concentration of 5% (m/v) was performed. A Box-Behnken experimental design was used. Lignocellulosic material was characterized by cellulose (30.57 ± 1.00%), hemicellulose (15.08 ± 0.65%), lignin (36.02 ± 1.05%), extractives (7.49 ± 0.03%), and ash (1.53 ± 0.28%). The optimization was performed using the response surface methodology approach. The model provided a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.95. The predicted optimal conditions for the process were a reaction time of 100 min, NaOH concentration of 4% (m/v), and temperature of 120 °C, which allowed the authors to obtain a saccharification of approximately 47.9%.

Download PDF

Full Article

Valorization of Andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aubl.) Residues through Optimization of Alkaline Pretreatment to Obtain Fermentable Sugars

Leiliane do Socorro Sodré Souza,a,* Anderson Mathias Pereira,b Marco Antônio dos Santos Farias,c Rafael Lopes e Oliveira,d Sérgio Duvoisin, Jr.,d and João Nazareno Nonato Quaresma a

The residual peels of andiroba seeds were submitted to alkaline pretreatment that aimed to maximize the recovery of fermented sugar. Evaluation of the best operation performance via the reaction time variables (20, 60, and 100 min), NaOH concentration (2, 3, and 4% (m/v)), and temperature (60, 90, and 120 °C) at a fixed solids concentration of 5% (m/v) was performed. A Box-Behnken experimental design was used. Lignocellulosic material was characterized by cellulose (30.57 ± 1.00%), hemicellulose (15.08 ± 0.65%), lignin (36.02 ± 1.05%), extractives (7.49 ± 0.03%), and ash (1.53 ± 0.28%). The optimization was performed using the response surface methodology approach. The model provided a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.95. The predicted optimal conditions for the process were a reaction time of 100 min, NaOH concentration of 4% (m/v), and temperature of 120 °C, which allowed the authors to obtain a saccharification of approximately 47.9%.

Keywords: Optimization; Hydrolysis; Andiroba; Alkaline pretreatment

Contact information: a: Natural Resources Engineering of the Amazon (PRODERNA/ITEC), Federal University of Pará (UFPA), Rua Augusto Corrêa, CEP 66075-110, Belém, Pará, Brazil; b: Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), Av. General Rodrigo Octavio Jordão Ramos, CEP 69067-005, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil; c: Institute of Exact Sciences, Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), Av. General Rodrigo Octavio Jordão Ramos, CEP 69067-005, Manaus, Amazonas; d: School of Technology, State University of Amazonas (UEA), Av. Darcy Vargas, CEP 69058-807, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil; *Corresponding author: leilianesodre@gmail.com

INTRODUCTION

The sustainable development of the Amazon region is fundamental for the preservation of various species of fauna and flora. A great many plant species have potential in the production of medicines and cosmetics, among which is Andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aubl.) belonging to the Meliaceae family. These species usually produce 180 to 200 kg of seeds per plant/year, where approximately 60% of their weight is oil (Rizzini and Mors 1976); the seeds possess approximately 20% peel. Andiroba seed oil already has an established use in the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industry because of its analgesic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antitumor, antifungal ability, and anti-allergic properties, so associating applications with the residues of these processes completes the economic development and sustainability cycle for this raw material (Miranda, Jr. et al. 2012; Tanaka et al. 2012; Inoue et al. 2015; De Moraes et al. 2018; Oliveira et al. 2018). The seeds contain protein (40%), glycides (33.9%), fiber (6.1%), minerals (1.8%), and lipids (6.2%). The oil contained in the seeds is light yellow and extremely bitter. When subjected to a temperature below 25 °C, it solidifies. It includes substances such as olein, palmitin, and glycerin (Revilla 2001).

Processing these seeds generates important products and co-products. Among the co-products, andiroba peel deserves more attention, as it has the potential to become an alternative base product for the production of second-generation ethanol from the breakdown of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose of which it is composed. Lignocellulosic biomass from agriculture and forestry, which includes agro-industrial waste, industrial forestry waste, energy crops, solid urban waste, and other materials, is the most abundant fuel source available to be used as a raw material for biorefineries that complements oil refineries, as well as for platform chemicals (Jönsson and Martín 2016).

Converting lignocellulosic biomass to biofuels represents a viable option for improving energy security and potentially reducing greenhouse gas emissions (Wang et al. 2007). In countries such as Brazil, with the main economic focus on agricultural production, waste generation is inevitable, and this creates interest in second-generation renewable fuels (De Carvalho and Ferreira 2014). However, the cost of producing second-generation (2G) ethanol is highly sensitive to the cost of the raw material, process parameters, and conditions (Mishra and Ghosh 2020).

Generally, lignocellulosic biomass is mainly composed of cellulose (38 to 50%), hemicelluloses (23 to 32%), and lignin (15 to 25%), as well as small amounts of extractives (McKendry 2002). These components are strongly cross-linked, as well as linked through covalent or non-covalent bonds and form the lignocellulosic matrix. To date, several pretreatment processes have been developed that can be categorized into physical, chemical, physicochemical, biological processes, and some combinations of these processes. As each pretreatment process has advantages and disadvantages, some combinations of pretreatment processes not only can increase the accessibility of enzymes to cellulose, but also can facilitate the recovery of associated lignin and hemicelluloses to produce high-value products (Sun et al. 2016). Alkaline pretreatment is the most commonly used method for removing lignin and hemicelluloses from lignocellulosic materials. In this method, biomass is soaked in alkaline solutions, such as calcium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, sodium hydroxide, or ammonium, and then mixed at a suitable temperature over a certain period of time (Ibrahim et al. 2011). Sodium hydroxide is one of the strongest base catalysts, and its effectiveness of pretreatment is evidenced by a higher degree of enzymatic hydrolysis than that with other alkaline pretreatments (Kim et al. 2016). An efficient biomass pretreatment process often involves a combination of several factors, therefore modeling and optimization techniques may be employed to improve process efficiency (Betiku and Taiwo 2015). To overcome current energy problems, lignocellulosic biomass, in addition to green biotechnology, is expected to be the main focus of future research (Anwar et al. 2014).

Within this context, finding ways of obtaining energy from biomass sources, without these crops being associated as environmentally aggressive, as well as fuels from petroleum, is the basis for sustainable development.

Andiroba residues are a source of carbohydrates that can be used in biorefineries in the production of organic acids and ethanol. In this sense, this study deals with the evaluation of alkaline pretreatment through Box-Behnken experimental design to maximize the amount of reducing sugars released from andiroba peels via adjusting the variables of time, NaOH concentration, and temperature, using response surface methodology to assess the response in output in terms of saccharification.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Raw materials

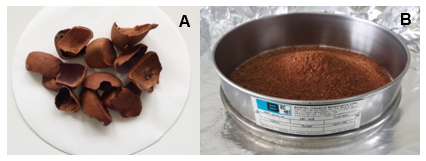

Andiroba seeds were collected in the municipality of Novo Airão, in the state of Amazonas, Brazil. The seeds were washed and subsequently subjected to drying in a circulating oven for 48 h at 50 °C. The seeds were peeled, and the peels were then milled in a laboratory knife mill (model TE-650; Tecnal, Piracicaba, Brazil) and after pass through a 1 mm sieve. Figure 1 shows the andiroba peels. The lignocellulosic material was subjected to preliminary characterization by elemental analysis (model 2400 Series II; PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Fig. 1. Andiroba peels: a) dried peels and b) the ground peels

Pretreatment

The andiroba peels were subjected to alkaline pretreatment with NaOH. These peels (5 g) were added to 100 mL (5% solids concentration) of NaOH solutions with different concentrations (2, 3, and 4%), and subjected to a heat treatment with varying temperatures (60, 90, and 120 °C) for different periods of time (20, 60, and 100 min). At the end of the process, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the pH was corrected to 5.0 ± 0.1 with H2SO4 in the enzymatic hydrolysis step. Thereafter, the treated peels were vacuum filtered (28 μm average pore size filter paper), and the collected solid was washed with 100 mL of distilled water, acid, or free alkali. Free acid or alkali may change the pH of the solution to values outside the range of enzymatic activity and the hydrolysate may contain inhibitory degradation products. The solid fraction was collected. The effects of time, NaOH concentration, and temperature on the saccharification were studied according to a statistical experimental design. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Methods

Enzymatic hydrolysis

After pretreatment, the obtained material was submitted to enzymatic hydrolysis for production and quantification of reducing sugars. Enzymatic hydrolysis was performed using a solids concentration of 5% (m/v) and enzymatic loading of 15 FPU/g of cellulose. The pH of the samples was adjusted to 4.8 ± 0.1 with 0.05 M citrate buffer, and the 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks with 100 mL reaction volume were maintained at 50 °C. The commercial enzyme Celluclast® 1.5 L (Novozymes, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used. Enzyme activity (47 FPU/mL) was determined according to the method described by Ghose (1987). Saccharification was calculated using Eq. 1:

Saccharification (%) =(g reducing sugars) / (g cellulose in pretreated biomass) × 100 (1)

Analysis

The quantification of cellulose and hemicellulose was performed using the Van Soest method (Van Soest 1963). Acid-insoluble lignin, ash, and extractives were determined according to the Sluiter et al. (2010) procedure. The lipid content of andiroba peel was determined following the American Oil Chemist’s Society methodology (AOCS 2004). Fermentable sugar (g/L) was quantified as the total amount of reducing sugars released into the pretreated sample using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid method (Miller 1959). Analyses were performed in triplicate and mean values are shown.

Experimental design

The optimization was based on the Box-Behnken experimental design, and applied to optimization procedures. The model consists of repeating the central points to measure experimental variability plus a set of factor points anchored at the central point defining the region of interest (Box and Behnken 1960). The selection of factor levels (Table 1) was based on the work with similarly constituted materials (Kim and Han 2012; Zulkefli et al. 2017; Buratti et al. 2018; González-Llanes et al. 2018).

Table 1. Independent Variables and Their Coded Values

The three pretreatment factors were chosen as X1, X2, and X3, which were defined at three levels coded as -1, 0, and +1. The experimental design consisted of 15 runs, as shown in Table 2, and these experiments allowed us to determine the effect of each independent process variable (reaction time, NaOH concentration, and temperature) and the interaction between these variables with the dependent variable (saccharification).

Statistical software (StatSoft Inc., STATISTICA 7, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to perform analysis of variance (ANOVA), with a significance level of 95% (p = 0.05), and generated response surfaces. Experimental data were evaluated using the response surface regression, which was given by the following polynomial Eq. 2,

y = β0 + β1X1 + β2X2 + β3X3 + β12X1X2+ β13X1X3 + β23X2X3 + β11X21 + β22X22 + β33X23 (2)

where y is the dependent variable, X1, X2, and X3 are the independent variables, β1, β2, and β3 are the linear coefficients, β12, β13, and β23 are interaction coefficients, and β11, β22, and β33 are the second order or quadratic coefficients. The response surface and contour plots were drawn using the quadratic polynomial equation obtained from the regression equation.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analyses

The dried samples were fixed with carbon tape onto the stubs. Subsequently, they were metallized via the BAL-TEC SCD 050 sputter coater equipment (Bal-Tec, Balzers, Liechtenstein) with a thin layer of gold, which left them electrically conductive and permitted their visualization. Afterwards, the evaluation was performed by observation through the SEM; the instrument used was the TESCAN-MEV VEGA 3 (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic). The FTIR analysis was performed using the Shimadzu model FTIR spectrophotometer IRAffinity-1S (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) with an ATR-8000 attachment (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The spectrum was obtained by attenuating horizontal reflection of ZnSe prism with 64 scans. The spectra were obtained in transmittance mode, with a measuring range from 500 to 4000 cm-1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemical Characteristics of Lignocellulosic Material

The results of chemical characterization, expressed as a percentage of weight in the dry base, showed that the andiroba peel presented a large amount of cellulose with a content of 36.96 ± 1.00%, followed by acid insoluble lignin, with approximately 36.02 ± 1.05%, hemicellulose 16.74 ± 0.65%, ash 1.53 ± 0.28%, and the extractives 7.49 ± 0.03%. The sample obtained after pretreatment under the best conditions presented 54.77 ± 0.67% cellulose, 12.38 ± 0.34% hemicellulose, and 23.52 ± 0.12% acid insoluble lignin. The amount of lignin was reduced by 34.7%, which justified the increase in the percentage of cellulose. The hemicellulose fraction had its quantity reduced approximately 26%.

The moisture of the raw material was 9.21 ± 0.08%. Because it is the peel of an oily seed, the amount of lipids within the chemical composition was investigated, and the determined value was 1.93 ± 0.03%, which was included in the percentage of the extractives. Similar results for chemical characterization were found for other materials used in lignocellulosic biomass conversion studies of fermentable sugars (Buratti et al. 2018; Bukhari et al. 2019; Li et al. 2019). The percentage of carbon (48.64 ± 0.09%), hydrogen (6.08 ± 0.15%), and nitrogen (0.52 ± 0.03%) in the composition of the andiroba peel are in agreement with the values found by López-González et al. (2013) for eucalyptus wood and pine bark.

Experimental optimization

In this study, the relationship between the saccharification and three process variables (reaction time, NaOH concentration, and temperature) was developed via response surface methodology. The experiments were based on the Box-Behnken matrix of experiments, and the experimental and predicted values of reducing sugars are presented in Table 2. In each experiment the amount of recovered solids was determined, and the results are also presented in Table 2.

The recovery of solids ranged from 61.9% to 81.5%; the lowest values were associated with higher temperature degrees under pretreatment conditions. Pretreatment with sodium hydroxide resulted in several structural modifications to lignocellulose, which were beneficial for enzymatic hydrolysis. Chemical bonds between the protective barrier of lignin and hemicellulose were broken.

Depending on the pretreatment conditions, lignin is partially or fully solubilized, and the degradation of the hemicellulosic fraction may occur because hemicellulose has an amorphous, heterogeneous, branched structure with little resistance, which makes it more susceptible to solubilization than cellulose under the alkaline conditions (Xu and Cheng 2011; Modenbach 2013). Test runs 8 and 11 showed that lower solids recovery and higher values of saccharification were obtained after enzymatic hydrolysis.

Table 2. Box-Behnken Factorial Design Results of Recovery of Solids after Alkaline Pretreatment, and Obtained/Predicted Saccharification

These findings corroborate the theory of cellulosic fraction accessibility to cellulases due to the removal of the protection structures of the plant material. To evaluate the efficiency of alkaline pretreatment in andiroba peel, the resulting pretreated solids were enzymatically hydrolyzed under identical conditions. In general, the highest temperature, NaOH concentration, and time values of the pretreatment positively favored the enzymatic digestibility of biomass. Thus, the worst performance of enzymatic hydrolysis was determined in run 10 (60 min, 2%, and 60 °C), with approximately 9.9% of saccharification obtained, and in run 5 (20 min, 3%, and 60 °C) with 11.5% obtained, which suggested that the pretreatment conditions were not sufficient to make cellulose accessible to enzymes. The solutions with the highest concentration of reducing sugars were accomplished in runs 8 and 11, with 46.1% and 39.7%, respectively. Both runs were performed at a temperature of 120 °C.

Table 3. Estimation of Effects and Coefficients

X1, X2, and X3 correspond to reaction time (min), NaOH (%), and temperature (°C), respectively; (L): linear; (Q): quadratic

In the first analysis, it was observed that the individual variables X1(L), X2(L), and X3(L) had statistical significance. The statistical variable p indicates the probability that each variable must not be considered statistically significant for the response variable, i.e., that it is within the null hypothesis acceptance region, in which case the effects are considered only as random errors and statistically not significant.

This confirmed that the operational variables for reaction time, NaOH concentration, and temperature have an influence on the process of production of fermentable sugars, because the p values for X1, X2, and X3 were 0.032307, 0.024097, and 0.000250, respectively, all below the significance level of 0.05. Regarding the effects of statistically significant variables, they have a (+) sign, i.e., a higher value resulted in a better response, for this study, which corresponds to the saccharification in the enzymatic hydrolysis (Montgomery 2001; Rodrigues and Iemma 2014). The significance of the equation was evaluated by ANOVA and the results showed that the model was highly significant where p = 0.000003. Similarly in Table 3, the t-test was performed to determine the importance of the regression coefficient.

Table 4. Analysis of Variance

The obtained results showed that the whole linear coefficient (time, concentration, and temperature) influenced the saccharification resulting from enzymatic hydrolysis. However, the interaction coefficients, which consist of three variables, X1X2 (L) (p = 0.874988), X1X3 (L) (p = 0.111381), and X2X3 (L) (p = 0.103909), were insignificant for statistical evaluation. Regarding the analysis of the t-test, a greater magnitude of “t” and a smaller value of “p” led to a more significant corresponding coefficient. The value of the coefficient of determination R2 was 0.9585 and the adjusted coefficient (Adj. R2) was 0.8838, which suggested that the model was highly predictive (Montgomery 2001). The Pareto chart in Fig. 2 is a tool that allows visual comparison between the effects linear, quadratic and the interactions, generated by the independent variables, time (X1), % NaOH (X2) and temperature (X3). Variables with statistical significance are presented as those that reach the right side of the graph. The columns represent the magnitude of the effects.

The efficiency of different operational factors in saccharification of Andiroba peel occurred in the following order: reaction temperature > sodium hydroxide concentration > reaction time. Thus, the reaction temperature, sodium hydroxide concentration, and reaction time had a significant effect on the saccharification. The polynomial model developed for the optimization of fermentable sugar production is presented in Eq. 3, via the relationship between saccharification and time, NaOH concentration, and temperature:

Saccharification = 23.7462 + 3.75814X1 + 4.08753X2 + 11.80954X3 (3)

This equation can be used to predict the saccharification. In addition to explaining the linear effects of time, NaOH concentration, and temperature on the production of fermentable sugars, the analysis also described the quadratic and interaction effects of the parameters.

Fig. 2. Pareto chart for time (X1), % NaOH (X2) and temperature (X3)

The experimental results were visualized in the three-dimensional response surface graphs that indicated the correlation between two variables with one variable being kept constant in its ideal condition and they are presented in Fig. 3.

In Fig. 3(a), it was observed that to reach the region with the highest values of saccharification, a reaction time greater than 90 min was required, even in NaOH concentration ranges at the intermediate level (3%). The effect of temperature was evident because the independent variable of greatest effect on the response variable of this study improved the efficiency of pretreatment at its highest level (120 °C). This range of higher amount of reducing sugars was observed mainly in reaction times between 60 and 100 min. Literature data confirmed the importance of temperature during alkaline pretreatment; values between 100 and 120 °C correlated with different concentrations and reaction times generally led to higher yields of reducing sugars (Kim et al. 2016; Buratti et al. 2018; Qing and Wyman 2011). The importance of assessing how temperature influenced the saccharification process lies in determining at which values it may have a negative effect on the response. Higher pretreatment temperature values may cause an increase in Klason lignin content and consequently a reduction in the efficiency of the enzymatic hydrolysis process, a fact that is associated with lignin recondensation, which results in a lower accessibility to the enzyme (Kim and Han 2012; Tye et al. 2017). Because temperature had a greater influence on the process, higher values of saccharification were only obtained at higher temperature values, as shown in the Fig. (b). In Fig. (c) it can be observed that the region with the highest saccharification was the region of 3 to 4% concentration of NaOH solution associated with higher temperatures values. In general, the alkaline pretreatment of biomass was highly effective for removing hemicellulose and lignin, but the outcome depends on catalyst concentration (Kang et al. 2013).

Fig. 3. Response surfaces for saccharification: a) Time vs. % NaOH (Temperature = 90ºC), b) Time vs. Temperature (NaOH = 3%), and c) % NaOH vs. Temperature (Time = 60 min)

According to the analysis of the independent variable effects on the answer variable, only linear effects were statistically significant. As these were positive, there were higher conversion values associated with higher independent variables values. Therefore, because of the maximization of saccharification used as optimization criterion, the model showed the best results related to a pretreatment condition of 100 min, 4% (m/v) NaOH, and 120 ºC, using a solids concentration of 5%.

The best conditions for saccharification of andiroba peel occurred under conditions that the Box-Behnken experimental design was not able to test. In this sense, another experiment was performed to test these conditions, and the model predictions were confirmed. The saccharification of the raw material and the sample treated under the best conditions of alkaline process were compared using solids concentration of 5%, enzymatic load of 15 FPU/g of cellulose, and time of 48 h ranged from 47.89 ± 0.82% (treated) to 4.14 ± 0.05% (raw material). The pretreatment was decisive for increasing the efficiency of enzymatic hydrolysis.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

The FTIR analysis was performed to determine the structural changes in lignocellulosic material after pretreatment with NaOH. The FTIR results can provide quantitative and qualitative data for compositional analysis of lignocellulosic biomass. The reduction in peak intensity indicates that the functional groups are altered or disturbed (Zulkefli et al. 2017). The FTIR spectroscopy data showed the occurrence of lignocellulosic structures including lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, for the untreated and treated in the best conditions biomass, according to Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. The FTIR spectra of untreated and pretreated lignocellulosic material under optimal conditions

The observed band at 1028 cm-1 was related to the vibration of C-O stretch in cellulose, and this peak became more pronounced in the treated sample, which indicated that the hemicellulose was removed and the characteristic cellulose peak was improved after alkaline pretreatment (Chen et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2016). The band detected at 3342 cm-1 was related to the stretching of O-H bonds in cellulose structures (Aruwajoye et al. 2019). Peaks observed at 1506 cm-1 in the treated and untreated samples corresponded to the absorption bands of the lignin functional groups (hydroxyl (OH), methoxyl, carbonyl group (C=O), and aromatic rings); the lignin was confirmed by the diagnostic aromatic skeletal absorbance between 1500 and 1560 cm−1 (Watkins et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2019). At 1604 cm-1 there was a reduction in the peak height from the untreated sample to the treated sample, indicating the removal of lignin (Zhu et al. 2016). The peak at 2921cm-1 was close to the spectral region attributed to C-H (asymmetric) deformation in methoxyl and methylene groups, which also indicates a slight change in lignin aromatic structures during the delignification process (Yiin et al. 2018).

Regarding the band observed at 1743 cm-1, the absence of the absorption band in the region between 1750 and 1700 cm-1 indicates that lignin was removed during the alkaline process; however, the peak at 1422 cm-1 was related to the aromatic skeletal vibrations; this implies that the core of the lignin structure was not significantly altered during the process, and it was not possible to remove all the lignin present in the biomass (Muñoz et al. 2019; Ying et al. 2018).

The absorption peak at 895 cm-1 may be related to the damaged β-glycosidic bonds within cellulosic structures. According to literature data, this absorption band indicates the presence of amorphous cellulose, and in Fig. 4 it is observed that this peak was more pronounced in the pretreated sample; thus the amorphous cellulose increased and the material was more easily hydrolyzed (Ebrahimi et al. 2017).

Scanning electron microscopy

The SEM allowed the evaluation of morphological changes resulting from alkaline pretreatment. In Fig. 5, the images of the lignocellulosic biomass treated with NaOH under the optimal conditions (5b and 5d) were compared with that of the untreated peel (5a and 5c) in the magnification of 1000× and 5000×, respectively.

The untreated peel of Andiroba had a compact, smooth surface with no trace of erosion or peeling. After pretreatment with sodium hydroxide, the sample surface showed irregular traces of erosion and pores. This erosion increased the accessible surface area of cellulose, which is important for the improvement of enzymatic hydrolysis. The pores became visible due to the removal of other cell wall components, leaving an exposed cellulose network (Lima et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2016). In Fig. 5b, it is possible to observe that in addition to the delaminated fibers, there were droplets present, and these possibly originated from the cellulosic matrix and were deposited back on the cell wall surface. These are probably aggregates of lignin, formed by lignin extraction from the inner regions of the cell wall, followed by condensation due to surface pH and redeposition conditions (Selig et al. 2007). Peeling residues were also observed in pretreated sugarcane bagasse SEM analysis (Chen et al. 2012). The presence of pores in the pretreated material can be seen in Fig. 5b and 5d, and this increase in porosity and external surface area is due to the rupture of the carbohydrate-lignin matrix as well as depolymerization and the solubilization of hemicellulosic polymers (Ramos 2003; Kamalini et al. 2018). Thus, delignification of lignocellulosic biomass with NaOH by forming voids on the material surface, increases the accessibility of cellulose and promotes an efficient enzymatic saccharification process.

Fig. 5. SEM images of untreated and pretreated andiroba peel prior to enzymatic hydrolysis: a, c: untreated raw material (1000×, 5000× magnification, respectively); b, d: pretreated under optimal conditions (1000×, 5000× magnification, respectively)

CONCLUSIONS

- The production of fermentable sugars from Andiroba seed peel was optimized for alkaline pretreatment. Reaction time, NaOH concentration, and temperature exerted linear effects on the response variable, saccharification (%).

- In the investigated experimental region, the highest concentration of reducing sugars was obtained at 100 min reaction time, 4% (m/v) NaOH concentration, and 120 °C temperature.

- The results obtained in the present study allow this biomass to be considered as a promising material for the production of fermentable sugars.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes, Brazil) for their financial support.

REFERENCES CITED

American Oil Chemist’s Society (AOCS) (2004). Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemist’s Society, AOAC Press, Champaign, IL, USA.

Anwar, Z., Gulfrazb, M., and Irshad, M. (2014). “Agro-industrial lignocellulosic biomass a key tounlock the future bio-energy: A brief review,” Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 7(2), 163-173. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrras.2014.02.003

Aruwajoye, G. S., Faloye, F. D., and Kana, E. G. (2019). “Process optimisation of enzymatic saccharification of soaking assisted and thermal pretreated cassava peels waste for bioethanol production,” Waste and Biomass Valorization (Online). DOI: 10.1007/s12649-018-00562-0

Betiku, E., and Taiwo, A. E. (2015). “Modeling and optimization of bioethanol production from breadfruit starch hydrolyzate vis-à-vis response surface methodology and artificial neural network,” Renewable Energy 74, 87-94. DOI: 10.1016/j.renene.2014.07.054

Box, G. E. P., and Behnken, D. W. (1960). “Some new three level designs for the study of quantitative variables,” Technometrics 2(4), 455-475. DOI: 10.2307/1266454

Bukhari, N. A., Jahim, J. M., Loh, S. K., Nasrin, A. B., and Luthfi, A. A. I. (2019). “Response surface optimisation of enzymatically hydrolysed and dilute acid pretreated oil palm trunk bagasse for succinic acid production,” BioResources 14(1), 1679-1693. DOI: 10.15376/biores.14.1.1679-1693

Buratti, C., Foschini, D., Barbanera, M., and Fantozzi, F. (2018). “Fermentable sugars production from peach tree prunings: Response surface model optimization of NaOH alkaline pretreatment,” Biomass and Bioenergy 112, 128-137. DOI: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2017.12.032

Chen, W. H., Ye, S. C., and Sheen, H. K. (2012). “Hydrolysis characteristics of sugarcane bagasse pretreated by dilute acid solution in a microwave irradiation environment,” Applied Energy 93, 237-244. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.12.014

De Carvalho, A. P. C., and Ferreira, R. L. (2014). “A utilização do biocombustível como alternativa sustentável na matriz energética brasileira [The use of biofuel as a sustainable alternative within the Brazilian energy matrix],” Caderno Meio Ambiente e Sustentabilidade [Notebook Environment and Sustainability 5(3), 139-157.

De Moraes, A. R. D. P., Tavares, G. D., Rocha, F. J. S., De Paula, E., and Giorgio, S. (2018). “Effects of nanoemulsions prepared with essential oils of copaiba- and andiroba against Leishmania infantum and Leishmania amazonensis infections,” Experimental Parasitology 187, 12-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.exppara.2018.03.005

Ghose, T. K. (1987). “Measurement of cellulose activities,” Pure and Applied Chemistry 59(2), 257-268. DOI: 10.1351/pac198759020257

González-Llanes, M. D., Hernandez-Calderon, O. M., Rios-Iribe, E. Y., Alarid-Garcıa, C., Montoya, A. J. M., and Escamilla-Silva, E. M. (2018). “Fermentable sugars production by enzymatic processing of agave leaf juice,” The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 96(3), 639-650. DOI: 10.1002/cjce.22959

Ibrahim, M. M., El-Zawawy, W. K., Abdel-Fattah, Y. R., Soliman, N. A., and Agblevor, F. A. (2011). “Comparison of alkaline pulpine with steam explosion for glucose production from rice straw,” Carbohydrate Polymers 83(2), 720-726. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.08.046

Inoue, T., Matsui, Y., Kikuchi, T., Yamada, T., In, Y., Muraoka, O., Sakai, C., Ninomiya, K., Morikawa, T., and Tanaka, R. (2015). “Carapanolides M-S from seeds of andiroba (Carapa guianensis, Meliaceae) and triglyceride metabolism-promoting activity in high glucose-pretreated HepG2 cells,” Tetrahedron 71(18), 2753-2760. DOI: 10.1016/j.tet.2015.03.017

Jönsson, L. J., and Martín, C. (2016). “Pretreatment of lignocellulose: Formation of inhibitory by-products and strategies for minimizing their effects,” Bioresource Technology 199, 103-112. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.009

Kamalini, A., Muthusamy, S., Ramapriya, R., Muthusamy, B., and Pugazhendhi, A. (2018). “Optimization of sugar recovery efficiency using microwave assisted alkaline pretreatment of cassava stem using response surface methodology and its structural characterization,” Journal of Molecular Liquids 254(15), 55-63. DOI: 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.091

Kang, K. E., Han, M. H., Moon, S. K., Kang, H. W., Kim, Y., Cha, Y. L., and Choi, G. W. (2013). “Optimization of alkali-extrusion pretreatment with twin-screw for bioethanol production from Miscanthus,” Fuel 109, 520-526. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.03.026

Kim, I., and Han, J. I. (2012). “Optimization of alkaline pretreatment conditions for enhancing glucose yield of rice straw by response surface methodology,” Biomass and Bioenergy 46, 210-217. DOI: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.08.024

Kim, J. S., Lee, Y. Y., and Kim, T. H. (2016). “A review on alkaline pretreatment technology for bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass,” Bioresource Technology 199, 42-48. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.085

Li, H., Chen, X., Xiong, L., Luo, M., Chen, X., Wang, C., Huang, C., and Chen, X. (2019). “Stepwise enzymatic hydrolysis of alkaline oxidation treated sugarcane bagasse for the co-production of functional xylo-oligosaccharides and fermentable sugars,” Bioresource Technology 275, 345-351. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.12.063

Lima, M. A., Lavorente, G. B., Da Silva, H. K. P., Bragatto, J., Rezende, C. A., Bernardinelli, O. D., Azevedo, E. R., Gomez, L. D., McQueen-Mason, S. J., Labate, C. A., et al. (2013). “Effects of pretreatment on morphology, chemical composition and enzymatic digestibility of eucalyptus bark: A potentially valuable source of fermentable sugars for biofuel production – Part 1,” Biotechnology for Biofuels 6, Article Number 75. DOI: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-75

López-González, D., Fernandez-Lopez, M., Valverde, J. L., and Sanchez-Silva, L. (2013). “Thermogravimetric-mass spectrometric analysis on combustion of lignocellulosic biomass,” Bioresource Technology 143, 562-574. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.06.052

McKendry, P. (2002). “Energy production from biomass (part 1): Overview of biomass,” Bioresource Technology 83(1), 37-46. DOI: 10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00118-3

Miller, G. L. (1959). “Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugars,” Analytical Chemistry 31(3), 426-428. DOI: 10.1021/ac60147a030

Miranda, Jr., R. N. C., Dolabela, M. F., Da Silva, M. N., Póvoa, M. M., and Maia, J. G. S. (2012). “Antiplasmodial activity of the andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aubl., Meliaceae) oil and its limonoid-rich fraction,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 142(3), 679-683. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.037

Mishra, A., and Ghosh, S. (2020). “Saccharification of kans grass biomass by a novel fractional hydrolysis method followed by co-culture fermentation for bioethanol production,” Renewable Energy 146, 750-759. DOI: 10.1016/j.renene.2019.07.016

Modenbach, A. (2013). Sodium Hydroxide Pretreatment of Corn Stover and Subsequent Enzymatic Hydrolysis: An Investigation of Yields, Kinetic Modeling and Glucose Recovery, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

Montgomery, D. C. (2001). Design and Analysis of Experiments, 5th Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Muñoz, A. H. S., Guerrero, C. E. M., Ortega, N. L. G., Vaca, J. C. L., Vargas, A. A., and Canchola, C. C. (2019). “Characterization and integrated process of pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of corn straw,” Waste and Biomass Valorization 10, 1857-1871. DOI:10.1007/s12649-018-0218-9

Oliveira, I. S. S., Tellis, C. J. M., Chagas, M. S. S., Behrens, M. D., Calabrese, K. S., Abreu-Silva, A. L., and Almeida-Souza, F. (2018). “Carapa guianensis aublet (andiroba) seed oil: Chemical composition and antileishmanial activity of limonoid-rich fractions,” BioMed Research International 2018, Article ID 5032816. DOI: 10.1155/2018/5032816

Qing, Q., and Wyman, C. E. (2011). “Supplementation with xylanase and b-xylosidase to reduce xylo-oligomer and xylan inhibition of enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose and pretreated corn stover,” Biotechnology for Biofuels 4, 1-12. DOI: 10.1186/1754-6834-4-18

Ramos, L. P. (2003). “The chemistry involved in the steam treatment of lignocellulosic materials,” Química Nova 26(6), 863-871. DOI: 10.1590/S0100-40422003000600015

Revilla, J. (2001). “Amazonian Plants: Economic and Sustainable Opportunities,” Manaus: Inpa: Sebrae.

Rizzini, C. T., and Mors, W. B. (1976). Brazilian Economic Botany, Escola Politécnica of the University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Rodrigues, M. I., and Iemma, A. F. (2014). Planejamento de Experimentos e Optimização de Processos [Experiment Planning and Process Optimization], 3rd Edition, Casa do Pão Editora, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil.

Selig, M. J., Viamajala, S., Decker, S. R., Tucker, M. P., Himmel, M. E., and Vinzant, T. B. (2007). “Deposition of lignin droplets produced during dilute acid pretreatment of maize stems retards enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose,” Biotechnology Progress 23(6), 1333-1339. DOI: 10.1021/bp0702018

Sluiter, J. B., Ruiz, R. O., Scarlata, C. J., Sluiter, A. D., and Templeton, D. W. (2010). “Compositional analysis of lignocellulosic feedstocks. 1. Review and description of methods,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 58(16), 9043-9053. DOI: 10.1021/jf1008023

Sun, S., Sun, S., Cao, X., and Sun, R. (2016). “The role of pretreatment in improving the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic materials,” Bioresource Technology 199, 49-58. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.061

Tanaka, Y., Sakamoto, A., Inoue, T., Yamada, T., Kikuchi, T., Kajimoto, T., Muraoka, O., Sato, A., Wataya, Y., Kim, H. S., et al. (2012). “Andirolides H-P from the flower of andiroba (Carapa guianensis, Meliaceae),” Tetrahedron 68(18), 3669-3677. DOI: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.12.076

Tye, Y. Y., Leh, C. P., and Abdullah, W. N. W. (2017). “Total glucose yield as the single response in optimizing pretreatments for Elaeis guineensis fibre enzymatic hydrolysis and its relationship with chemical composition of fibre,” Renewable Energy 114(B), 383-393. DOI: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.07.040

Van Soest, P. J. (1963). “Use of detergents in the analysis of fibrous feeds. II. A rapid method for the determination of fibre and lignin,” Journal of the Association of the Official Agricultural Chemists 46, 829-835.

Wang, H., Pu, Y., Ragauskas, A., and Yang, B. (2019). “From lignin to valuable products–strategies, challenges, and prospects,” Bioresource Technology 271, 449-461. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.09.072

Wang, M., Wu, M., and Huo, H. (2007). “Life-cycle energy and greenhouse gas emission impacts of different corn ethanol plant types,” Environmental Research Letters 2(2), 1-14. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/2/2/024001

Watkins, D., Nuruddin, M., Hosur, M., Tcherbi-Narteh, A., and Jeelani, S. (2015). “Extraction and characterization of lignin from different biomass resources,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology 4(1), 26-32. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2014.10.009

Xu, J., and Cheng, J. J. (2011). “Pretreatment of switchgrass for sugar production with the combination of sodium hydroxide and lime,” Bioresource Technology 102(4), 3861-3868. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.12.038

Yiin, C. L., Yusup, S., Quitain, A. T., Uemura, Y., Sasaki, M., and Kida, T. (2018). “Delignification kinetics of empty fruit bunch (EFB): A sustainable and green pretreatment approach using malic acid‑based solvents,” Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 20(9), 1987-2000. DOI: 10.1007/s10098-018-1592-5

Ying, W., Shi, Z, Yang, H., Xu, G., Zheng, Z., Yang, J. (2018). “Effect of alkaline lignin modification on cellulase–lignin interactions and enzymatic saccharification yield.” Biotechnology for Biofuels 11, 214. DOI: 10.1186/s13068-018-1217-6

Zhu, Z., Rezende, C. A., Simister, R., McQueen-Mason, S. J., Macquarrie, D. J., Polikarpov, I., and Gomez, L. D. (2016). “Efficient sugar production from sugarcane bagasse by microwave assisted acid and alkali pretreatment,” Biomass and Bioenergy 93, 269-278. DOI: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2016.06.017

Zulkefli, S., Abdulmalek, E., and Rahman, M. B. A. (2017). “Pretreatment of oil palm trunk in deep eutectic solvent and optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated oil palm trunk,” Renewable Energy 107, 36-41. DOI: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.01.037

Article submitted: September 12, 2019; Peer review completed: November 17, 2019; Revised version received: December 10, 2019; Accepted: December 12, 2019; Published: December 17, 2019.

DOI: 10.15376/biores.15.1.894-909