Abstract

Algae constitute a diverse group that is useful in many biotechnological areas. In this paper, the usefulness of Caulerpa sertularioides methanol extract in the synthesis of ZnO and Zn(OH)2 nanoparticles was explored. This work had two main objectives: (1) to use the extract in the synthesis as an organic harmless complexing agent, and (2) to enhance a photocatalytic effect over AZO dyes in wastewater from fabric industries without adding nanomaterial to the environment due to its toxicity. Caulerpa extract performed the expected complexing action, and nanoparticles were formed in a size range from 45 to 69 nm. X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and UV-Vis spectroscopy were used to characterize the system. It was demonstrated that the nanoparticles were useful to photocatalyst AZO dyes in the water, while contained in tetraethylorthosilicate composites. These could be used in industrial wastewater and are expected to have no environmental consequences because the composites do not add nanoparticles to the water.

Download PDF

Full Article

Caulerpa sertularioides Extract as a Complexing Agent in the Synthesis of ZnO and Zn(OH)2 Nanoparticles and its Effect in the Azo Dye’s Photocatalysis in Water

Daniel Garcia-Bedoya,a,d Luis P. Ramírez-Rodríguez,b Jesús M. Quiroz-Castillo,c Edgard Esquer-Miranda,d and Arnulfo Castellanos-Moreno b,*

Algae constitute a diverse group that is useful in many biotechnological areas. In this paper, the usefulness of Caulerpa sertularioides methanol extract in the synthesis of ZnO and Zn(OH)2 nanoparticles was explored. This work had two main objectives: (1) to use the extract in the synthesis as an organic harmless complexing agent, and (2) to enhance a photocatalytic effect over AZO dyes in wastewater from fabric industries without adding nanomaterial to the environment due to its toxicity. Caulerpa extract performed the expected complexing action, and nanoparticles were formed in a size range from 45 to 69 nm. X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and UV-Vis spectroscopy were used to characterize the system. It was demonstrated that the nanoparticles were useful to photocatalyst AZO dyes in the water, while contained in tetraethylorthosilicate composites. These could be used in industrial wastewater and are expected to have no environmental consequences because the composites do not add nanoparticles to the water.

Keywords: Nanotechnology; Nanoparticles; ZnO; Zn(OH)2; Caulerpa sertularioides.

Contact information: a: Posgrado en Nanotecnología, Universidad de Sonora, Apdo. Postal 1626 Col. Centro Hermosillo, Sonora C.P. 83000 MEXICO; b: Departamento de Física, Universidad de Sonora, Apdo. Postal 1626 Col. Centro Hermosillo, Sonora C.P. 83000 MEXICO; c: Departamento de Investigación en Polímeros, Universidad de Sonora, Apdo. Postal 1626 Col. Centro Hermosillo, Sonora C.P. 83000 MEXICO; d: Universidad Estatal de Sonora, Ley Federal del Trabajo S/N. Hermosillo, México;

* Corresponding author: acastellster@gmail.com

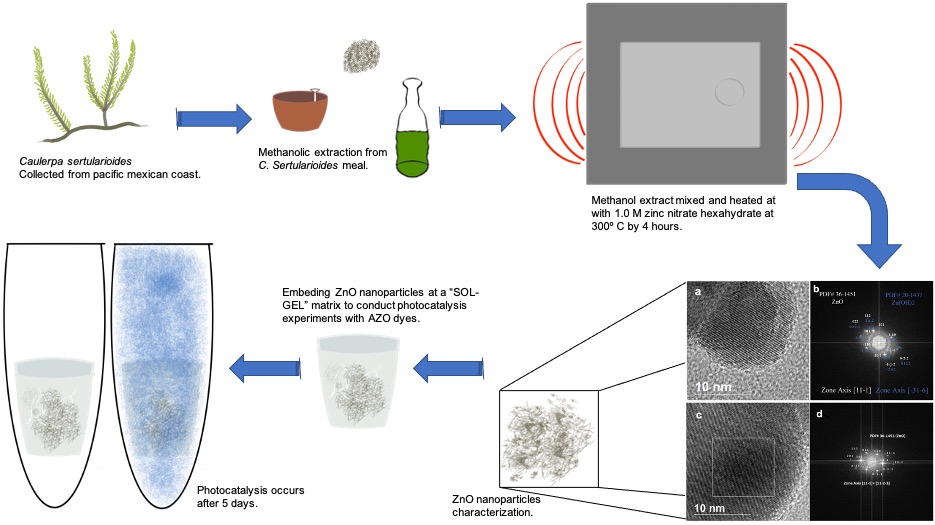

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Historically, the fabric industries have used dyes with toxicity issues, i.e., heavy metals such as Hg and Pb, and modern AZO dyes seem to be mutagenic and carcinogenic (Talaiekhozani et al. 2020; Eskandari et al. 2019). At first, this problem was manifested in the people who worked with the dyed materials, and now the problem has been transferred to the water used to pre-wash the fabrics or the clothes made with them (Daneshvar et al. 2008). The water used for dyes and the prewashed discharges must be treated to remove the colorants and leave the water dye-free before sending it to drainage systems or natural environments (Ventura-Camargo and Marin-Morales 2013).

As an option to deal with the colorants problem, ZnO and Zn(OH)2 nanostructured materials have been used to precipitate textile colorants or degrade them by photocatalysis (Xuejing et al. 2009; Bagheri et al. 2020). As some nanoparticles have a negative environmental impact due to possible toxicity, it is also important that nanotechnology proposals offer a way to introduce them to natural systems with the certainty that they will not harm any organism (Simeonidis et al. 2018). A particular trouble with the synthesis of nanoparticles is the use of precursors such as surfactants and complexing agents, which may be hazardous due to their organic origin, for example, thiourea, polyethyleneimine, thioacetamide, and triethanolamine (Knaak et al. 1997; Hajovsky et al. 2012; Oskuee et al. 2018; Chmielewska et al. 2018; Sen et al. 2020). The function of these products is to reduce and complex the metal ions in order to form the particles; these substances donate electrons and form bonds with the metals atoms (Peters 1999).

Some organic substances that offer these characteristics are extracted from the tissues of biological organisms (Sadeghi et al. 2015). Animals, plants, algae, and fungi tissues have metabolites that are reductive, can serve as complexing agents, but are harmless by oral, cutaneous, and respiratory exposure, which are the most frequent routes of intoxication (Gupta and Xie 2018). These metabolites may provide other characteristics to the nanoparticles by adding organic compounds that have many uses (disease treatments, antibiotic functions, etc.) to the nanoparticle surface (Virkutyte and Varma 2013). Algae are an excellent source of metabolites; this taxon is diverse, ranging from unicellular to multicellular forms. The marine group includes Caulerpa sertularioides (S. G. Gmelin), which is an abundant and resistant species that grows in coastal lagoons. With respect to the nanotechnology field, C. sertularioides contains sterols and metabolites that may be useful as reductive and complexing agents (Batley et al. 2013; Esquer-Miranda et al. 2016). In this study we use the C. sertularioides extract as a complexing agent to synthetize Zno and Zn(OH)2 nanoparticles and test its effect in the photocatalysis of an AZO commercial use dye.

EXPERIMENTAL

Methanol Extracts from Macroalgae C. sertularioides

The methodology for the algal extraction followed the one proposed in Coronado-Aceves et al. (2016), even in the collection sites provided. Macroalgae meal C. sertularioides was collected in Agiabampo Bay, Sonora (Mexico north-west coast). It was dried in a convection oven at 45 °C for 24 h, milled in a pulverizer, sifted through a 250 mm mesh sieve, and stored at 4 °C until use. Methanol extracts were obtained from 200 g of dried macroalgae meal in 2000 mL of 99.8% methanol. The extractions were performed at room temperature and stirred three times daily for seven days. The extracts were used to prepare nanoparticles.

Meal Analysis

The chemical analysis of the meals was made on an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer model 3110, Waltham, MA, USA).

Nanoparticles Synthesis

Nanoparticles were synthesized by methods adapted from Dobrucka and Dugaszewska (2016) and Sundrarajan et al. (2015). The formulation was performed as follows. 2.5 g of 1.0 M zinc nitrate hexahydrate were mixed with 25 mL of the C. sertularioides’s extract under vigorous stirring for 2 h, maintaining the temperature at 90 °C. After this time, the temperature was reduced to 30 °C until all the liquid (water plus methanol) was evaporated. It formed a green paste. This mass was burned in a muffle furnace at 300 °C for 4 h, producing a white powder.

Nanoparticles Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed to determine whether ZnO and Zn(OH)2 were present in the nanoparticles. The nanoparticles’ optical transmission spectrum was measured with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (model Lambda 20, Perkin Elmer). Structural properties were obtained through a transmission electronic microscope (TEM; model JEM-2010F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Other ions were identified by atomic absorption spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer model 3110).

Encapsulation

Due to ZnO nanomaterial’s toxicity, it was necessary to provide a method to maintain nanoparticles away from organisms when used in natural systems. Nanoparticles were encapsulated in a sol-gel matrix constructed with the following method. First, 0.5 g of of ZnO and Zn(OH)2 nanoparticles were suspended in 5 mL of water. The composites were made by mixing with 5 mL of ethanol and 5 mL of Si(OC2H5)4 (tetraethyl orthosilicate, reagent grade, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA ). Then, 1 mL of nitric acid (HNO3) (0.0974 mol) was added to homogenate the mix, in order to accelerate gelation 3 mL of NH4OH (0.0974 mol). The mix was stirred with a vortex (Greish and Brown 2001; Encinas-Romero et al. 2013) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Diagram for the sol-gel embedding method for nanoparticles encapsulation

Dyes Photocatalysis Experiments

There were two set of photocatalysis experiments with solar light. These experiments were contained in five 50-mL plastic centrifuge tubes per treatment. The control was deionized water with a commercial dye prepared as recommended by the retailer (1 g/L) (PUTNAM deep blue, “El Caballito”, Mexico, Mexico also known as Naphthol Blue Black). Treatment 1 was Sol Gel without ZnO encapsulation, and treatment 2 was ZnO encapsulated in a Sol-Gel matrix. All were placed on the roof of the Environmental Engineering building at Sonora State University for five days, and they were removed once a day for measurement. Transmittance were measured with a Konica Minolta spectrophotometer (Tokyo, Japan) for aliquots of each experiment treatment tube.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

X-ray diffraction results showed that after two independent processes, the synthesis of ZnO and Zn(OH)2 were reproduced by the PDF#36-1451 and PDF#20-1437, respectively, where the ZnO preference directions are (100), (002), (101), (103), (112), and (201). The XRD spectra had a somewhat disarranged appearance. This is a characteristic of an impure material, the material is not pure due to the elements bioaccumulated by the algae and because of the Zn(OH)2 formation, it is important to mention that these impurities were identified (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2015). The results suggested a mainly wurtzite hexagonal arrangement, and this material was consistent with the P63mc space group (Fig. 2).

Deionized water and ethylene glycol were used to suspend the material and measure the UV-Vis spectra and for the TEM; in both cases the results showed that the bandgap was lower than expected. ZnO and Zn(OH)2 must present around 3.37 eV (Hassan and Hashim 2012; Kumar et al. 2012). Using the Tauc method, the bandgap observed was 2.71 eV for the water suspension and 2.77 eV for water and ethylene glycol (Fig. 3). Both fluids were used to suspend the particles because ethylene glycol promotes the nanoparticles formation and could be useful to characterized the material with the TEM.

This variation must be obeyed by other ions impurities such as Pb, Cu, Cd, and Fe, which had been registered in the atomic spectroscopy performed for the meals (Table 1) and in the EDS analysis provided with the TEM micrographics. ZnO nanostructures doped with cooper showed exactly a 2.7 eV bandgap (Tyona et al. 2017). This result is consistent with the Uv-Vis optical resonance (367 nm) for ZnO nanoparticles (Bajpai et al. 2016).

Atomic absorption results showed that meal contained some metals (Table 1) including Cu. This analysis was performed because it is known that Cu and Fe interacts at quantic levels, changing the normal bandgap for the ZnO (Tyona et al. 2017). Copper concentrations were consistent with other Caulerpa species (Huili et al. 2019).

Table 1. Metallic Bioabsorption of C. sertularioides

Fig. 2. XRD diffraction spectra for the ZnO synthesized material measured in to separate occasions at two research institutions, CINVESTAV (Advanced Research Center) and UNISON (Universidad de Sonora)

Fig. 3. Uv-Vis spectra and curve used by the Kubelka–Munk model to determine the bandgap energy value

Observations by transmission electron microscopy showed that the nanoparticles ranged in size from 45 to 69 nm (Fig. 4) (Kisielowski et al. 2008; Haider et al. 2010; Smith 2012; Li and Ge 2019).

Fig. 4. HRTEM micrographs image for both suspensions). A, B, and C correspond to ZnO in water; D, E, and F correspond to Zn(OH)2 in ethylene glycol

Without encapsulation, all nanoparticles are hazardous to use in environmental matrixes. The size might be small enough to get through membranes and pores of tissues and even cells to show toxicity (Seaton et al. 2010; Maurer-Jones et al. 2013). The “rod” morphology of ZnO it consistent with a polarized growth of the crystal. ZnO is composed of two crystalline planes that form a dipole moment and whose orientation is along the c axis; therefore, ZnO is a polar semiconductor and, due to this property, growth is along the c axis (Xian-Luo et al. 2004), to corroborate this a fast Fourier transformed (FFT) image analysis was performed in water and ethylene glycol samples (Fig. 5).

To corroborate that nanoparticles are not able to enter aquatic life forms, they were encapsulated in tetraethilortosilicate (TEOS) composites, and the UV-Vis spectra were measured in water samples containing composites with and without nanoparticles. As shown in Fig. 6, no particles were added to water during the experiment; the UV-Vis absorption spectra of ZnO and Zn(OH)2 must have sharp peaks from 390 to 494 nm (Zak et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2015). Furthermore, this analysis confirms that TEOS composites are a good method to encapsulate the nanoparticles.

A difference in efficiency was observed between composites with or without nanoparticles. While both treatments end with a 96% of transparency, the composites doped with ZnO nanoparticles cleaned the water a day faster. This may not develop a new cleaning water technology, but it demonstrates that nanoparticles have a positive effect on the treatment of fabric dyes from water. The effect of ZnO nanoparticles coated by SiO2 was already tested to observe their photocatalytic properties with positive results (Zhai et al. 2010). The SiO2 powers the photocatalytic effects due to the Si electronegativity (Wang et al. 2009, 2010). The experiment also reveals that the synthetized materials were both a nanoscale material and a semiconductor, the last due to its photocatalytic effect (Hoffmann et al. 1995).

Fig. 5. HRTEM micrographs image for both suspensions. Micrographs a) and b) show ZnO and ZnOH identified by FFT analysis in waters samples. Micrographs c) and d) show ZnO identified by FFT analysis in ethylene glycol.

Fig. 6. UV-Vis spectra from water containing TEOS composites with and without nanoparticles

Finally, photocatalysis experiments showed that in 8 days approximately 96% of transparency can be achieved using the encapsulated nanoparticles or just the sol-gel composite (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Transmittance of the DYE dissolved in water and the synthesized nanomaterials’ photocatalytic effect: Control (Ctrl), SolGel without nanoparticles (sg), and Nanoparticles embedded in a sol gel composite (sgZnO)

When comparing the obtained results with previous articles, two different things were apparent. When using ZnO materials (nanoparticles or bulk), the used dye was methylene blue which has a weak chemical structure and can be oxidized in minutes or hours (Chen 2009), and when AZO dyes are used, the oxidant material is TiO2 or gold and the colorants frequently used are red or orange (Mrowetz et al. 2007). This study considered one of the most persistent dyes, which is the Naphthol Blue Black. This is photocatalyzed by TiO2 conventional nanoparticles (not a “green synthesis”) in about 2 days with an UV source (Nars et al. 1996; Saleh 2019) or other kind of blue that can be photocatalyzed in hours but using toxic precursors (Sasikala et al. 2016). Some other studies have achieved better results and are also based on “green synthesis”, but they use bacteria, which has to be isolated and doped by the ions of interest in order to grow nanoparticles in the colony, but the amount of obtained material is low in comparison with the algae or plant extracts (Noman et al. 2019)

This demonstrates that the technology from natural extracts can be useful even when the synthesized materials are not pure.

CONCLUSIONS

- ZnO nanoparticles were effectively present in the prepared composites, and this was supported by the UV-Vis optical resonance at 364 nm and the TEM (PDF#36-1451).

- ZnO nanoparticles were shown to be effective in removing AZO dyes from water.

- The embedding with a SiO2 sol-gel matrix embedding was shown to be a good way to avoid the nanoparticles and their dissemination to the aquatic environment without decreasing its photocatalytic effect but enhancing it.

- This material would be very effective in wastewater treatments in fabric industries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the personal in the “Semiconductores” lab at DIFUS-UNISON for their support and the training in the Sol-Gel method, and the “Departamento de Investigación en Polímeros y Materiales” for the TEM micrographs. The authors thank UES’s CA-Ingeniería Ambiental and the “Laboratorio de Calidad y Restauración del Agua” for their support and Ana Lourdes Partida Gámez for her revision to this manuscript. We also thank R.A. Rosas-Burgos, A. Corella-Madueño, R.P. Duarte-Zamorano, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions to improve this paper.

REFERENCES CITED

Bagheri, M., Najafabadi, N. R., and Borna, E. (2020). “Removal of Reactive Blue 203 dye photocatalytic using ZnO nanoparticles stabilized on functionalized MWCNTs,” Journal of King Saud University – Science 32, 799-804. DOI: 10.1016/j.jksus.2019.02.012.

Batley, G. E, Kirby, J. K, and McLaughlin, M. J. (2013). “Fate and risks of nanomaterials in aquatic and terrestrial environments,” Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 854-862. DOI: 10.1021/ar2003368

Chen, C.-Y. (2009). “Photocatalytic degradation of azo dye reactive orange 16 by TiO2,” Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 202(1-4), 335-342. DOI: 10.1007/s11270-009-9980-4

Chmielewska, R., Gawlak, M., Bamburowicz-Klimkowska, M., Popławska, M., and Grudziński, I. (2018). “Distribution of polyethylenimine in zebrafish embryos,” Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 69(3), 315-318.

Coronado-Aceves, E. W., Sánchez-Escalante, J. J., López-Cervantes, J., Robles-Zepeda, R. E., Velázquez, C., Sánchez-Machado, D. I., and Garibay-Escobar, A. (2016). “Antimycobacterial activity of medicinal plants used by the Mayo people of Sonora, Mexico,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 190, 106-115. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.05.064

Daneshvar, N., Aber, S., Vatanpour, V., and Rasoulifard, M. H. (2008). “Electro-Fenton treatment of dye solution containing Orange II: Influence of operational parameters,” Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 615(2), 165-174. DOI: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2007.12.005

Dobrucka, R., and Dugaszewska, J. (2016). “Biosynthesis and antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles using Trifolium pratense flower extract,” Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 23, 517-523. DOI: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.05.016

Encinas-Romero, M., Peralta-Haley, J., Valenzuela-García, J., and Castillón-Barraza, F. (2013). “Synthesis and structural characterization of hydroxyapatite-wollastonite biocomposites, produced by an alternative sol-gel route,” Journal of Biomaterials and Nanobiotechnology 4, 327-333. DOI: 10.4236/jbnb.2013.44041

Esquer-Miranda, E., Nieves-Soto, M., Rivas-Vega, M. E., Miranda-Baeza, A., and Pi, P. (2016). “Effects of methanolic macroalgae extracts from Caulerpa sertularioides and Ulva lactuca on Litopenaeus vannamei survival in the presence of Vibrio bactéria,” Fish Shellfish Immunol. 51, 346-350. DOI: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.02.028

Eskandari, Z., Talaiekhozani, A., Talaie, M. R., and Banisharif, F. (2019). “Enhancing ferrate(VI) oxidation process to remove blue 203 from wastewater utilizing MgO nanoparticles,” Journal of Environmental Management 231, 297-302. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.10.056

Greish, Y. E., and Brown, P.W. (2001). “Characterization of wollastonite-reinforced HAp-Ca polycarboxylate composites,” Journal of Biomedical Materials Research 55 4, 618-28. DOI: 10.1002/1097-4636%2820010615%2955%3A4%3C618%3A%3AAID-JBM1056%3E3.0.CO%3B2-9

Gupta, R., and Xie, H. (2018). “Nanoparticles in daily life: Applications, toxicity and regulations,” J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2018; 37(3), 209-230. DOI: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.2018026009

Haider, M., Hartel, P., Müller, H., Uhlemann, S., and Zach, J. (2010). “Information transfer in a TEM corrected for spherical and chromatic aberration,” Microscopy and Microanalysis 16(4), 393-408. DOI: 10.1017/S1431927610013498

Hajovsky, H., Hu, G., Koen, Y., Sarma, D., Cui, W., Moore, D. S., Staudinger, J. L., and Hanzlik, R. P. (2012). “Metabolism and toxicity of thioacetamide and thioacetamide S-oxide in rat hepatocytes,” Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25(9), 1955-63. DOI: 10.1021/tx3002719

Hassan, N. K., and Hashim, M. R. (2012). “Structural and optical properties of ZnO thin film prepared by oxidation of Zn metal powders,” International Conference on Enabling Science and Nanotechnology 1-2. DOI: 10.1109/ESciNano.2012.6149685

Hao, H., Fu, M., Yan, R., He, B., Li, M., Liu, Q., Cai, Y., Zhang, X., and Huang, R. (2019). “Chemical composition and immunostimulatory properties of green alga Caulerpa racemosa var peltata,” Food and Agricultural Immunology 30(1), 937-954. DOI: 10.1080/09540105.2019.1646216

Hoffmann, M. R., Martin, S. T., Choi, W., and Bahnemann, D. W. (1995). “Environmental applications of semiconductor photocatalysis,” Chemical Reviews 95(1), 69-96. DOI:10.1021/cr00033a004

Hu, X.-L., Zhu, Y.-J., and Wang, S.-W. (2004). “Sonochemical and microwave-assisted synthesis of linked single-crystalline ZnO rods,” Materials Chemistry and Physics 88(2-3), 421-426. DOI:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2004.08.010

Knaak, J. B., Leung, H. W., Stott, W. T., Busch, J., and Bilsky, J. (1997). “Toxicology of mono-, di-, and triethanolamine,” in: G.W. Ware (ed.), Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology (Continuation of Residue Reviews), Springer, New York. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2272-9_1

Kisielowski, C., Freitag, B., Bischoff, M., Van Lin, H., Lazar, S., Knippels, G., and Haider, M. (2008). “Detection of single atoms and buried defects in three dimensions by aberration-corrected electron microscope with 0.5-Å information limit,” Microscopy and Microanalysis 14(5), 469-477. DOI: 10.1017/S1431927608080902

Kumar, D., Jat, S. K., Khanna, P. K., Vijayan, N., and Banerjee, S. (2012). “Synthesis, characterization, and studies of PVA/Co-doped ZnO nanocomposite films,” International Journal of Green Nanotechnology 4(3), 408-416. DOI: 10.1080/19430892.2012.738509

Li, S., and Ge, B. (2020). “A review of sample thickness effects on high-resolution transmission electron microscopy imaging,” Micron 130, 102813. DOI: 10.1016/j.micron.2019.102813

Maurer-Jones, M. A, Gunsolus, I. L., Murphy, C. J., and Haynes, C. L. (2013). “Toxicity of engineered nanoparticles in the environment,” Anal Chem. 85(6), 3036-3049. DOI: 10.1021/ac303636s

Mrowetz, M., Villa, A., Prati, L., and Selli, E. (2007). “Effects of Au nanoparticles on TiO2 in the photocatalytic degradation of an azo dye,” Gold Bulletin 40(2), 154-160. DOI:10.1007/bf03215573

Mukhopadhyay, S., Das, P. P., Maity, S., Ghosh, P., and Devi, P. S. (2015). “Solution grown ZnO rods: Synthesis, characterization and defect mediated photocatalytic activity,” Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 165, 128-138. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.09.045

Nasr, C., Vinodgopal, K., Fisher, L., Hotchandani, S., Chattopadhyay, A. K., and Kamat, P. V. (1996). “Environmental photochemistry on semiconductor surfaces. Visible light induced degradation of a textile diazo dye, naphthol blue black, on TiO2 nanoparticles,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry 100(20), 8436-8442. DOI:10.1021/jp953556v

Noman, M., Shahid, M., Ahmed, T., Khan Niazi, M. B., Hussain, S., Song, F., and Manzoor, I. (2019). “Use of biogenic copper nanoparticles synthesized from a native Escherichia sp. as photocatalysts for azo dye degradation and treatment of textile effluents,” Environmental Pollution 113514. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113514

Oskuee, R. K., Dabbaghi, M., Gholami, L., Taheri‐Bojd, S., Balali-Mood, M., Mousavi, S. H., and Malaekeh-Nikouei, B. (2018). “Investigating the influence of polyplex size on toxicity properties of polyethylenimine mediated gene delivery,” Life Sciences 197, 101-108. DOI: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.02.008

Peters, R. W. (1999). “Chelant extraction of heavy metals from contaminated soils,” J. Hazard. Mater. 66, 151-210. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3894%2899%2900010-2

Sadeghi, B., Rostami, A., and Momeni, S. S. (2015). “Facile green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using seed aqueous extract of Pistacia atlantica and its antibacterial activity,” Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 134, 326-332. DOI: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.05.078

Saleh, S. M. (2019). “ZnO nanospheres based simple hydrothermal route for photocatalytic degradation of azo dye,” Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 211, 141-147. DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2018.11.065

Sasikala, R., Karthikeyan, K., Easwaramoorthy, D., Bilal, I. M., and Rani, S. K. (2016). “Photocatalytic degradation of trypan blue and methyl orange azo dyes by cerium loaded CuO nanoparticles 2,” Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management 6, 45-53. DOI:10.1016/j.enmm.2016.07.001

Seaton, A., Tran, L., Aitken, R., and Donaldson, K. (2010). “Nanoparticles, human health hazard and regulation,” Journal of the Royal Society, Interface 7(1), 119-129. DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0252.focus

Sen, G. T., Ozkemahli, G., Shahbazi, R., Erkekoglu, P., Ulubayram, K., and Kocer-Gumusel, B. (2020). “The effects of polymer coating of gold nanoparticles on oxidative stress and DNA damage,” International Journal of Toxicology 39(4), 1-13. DOI: 1091581820927646

Simeonidis, K., Martinez-Boubeta, C., Zamora-Perez, P., Rivera-Gil, P., Kaprara, E., Kokkinos, E., and Mitrakas, M. (2018). “Nanoparticles for heavy metal removal from drinking water,” In: Environmental Nanotechnology, N. Dasgupta, S. Ranjan, and E. Lichtfouse (eds.), Springer, Berlin. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-76090-2_3

Smith, D. K. (2012). “Progress and problems for atomic-resolution electron microscopy,” Micron 43(4), 504-508. DOI: 10.1016/j.micron.2011.09.012

Talaiekhozani, A., Banisharif, F., Eskandari, Z., Talaei, M. R., Park, J., and Rezania, S. (2020). “Kinetic investigation of 1,9-dimethyl-methylene blue zinc chloride double salt removal from wastewater using ferrate (VI) and ultraviolet radiation,” Journal of King Saud University – Science 32, 213-222. DOI: 10.1016/J.JKSUS.2018.04.010

Tyona, M. D., Osuji, R. U., Asogwa, P. U., Jambure, S. B., and Ezema, F. I. (2017). “Structural modification and band gap tailoring of zinc oxide thin films using copper impurities,” Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 21, 2629-2638. DOI: 10.1007/s10008-017-3533-3

Ventura-Camargo, B., and Marin-Morales M. (2013). “Azo dyes: Characterization and toxicity- A review,” Textiles and Light Industrial Science and Technology (TLIST) 2(2), 85-103.

Virkutyte, J., and Varma, R. S. (2013). “Environmentally friendly preparation of metal nanoparticles,” In: Sustainable Preparation of Metal Nanoparticles, Methods and Applications, R. Luque and R. S. Varma (eds.), Royal Society of Chemistry, London. DOI: 10.1007/s10311-017-0618-2

Wang, M., Jiang, L., Kim, E. J., and Hahn, S. H. (2015). “Electronic structure and optical properties of Zn(OH)2: LDA+U calculations and intense yellow luminescence,” RSC Advances 5(106), 87496-87503. DOI: 10.1039/c5ra17024a

Wang, J., Tsuzuki, T., Sun, L., and Wang, X. (2009). “Reducing the photocatalytic activity of zinc oxide quantum dots by surface modification,” J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 92 2083-2088. DOI: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03142.x

Wang, J., Tsuzuki, T., Sun, L., and Wang, X. (2010). “Reverse microemulsion-mediated synthesis of SiO(2)-coated ZnO composite nanoparticles: Multiple cores with tunable shell thickness,” ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2(4), 957-60. DOI: 10.1021/am100051z

Wijesinghe, W., and Jeon, Y. (2012). “Enzyme-assistant extraction (EAE) of bioactive components: A useful approach for recovery of industrially important metabolites from seaweeds: A review,” Fitoterapia 83(1), 6-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.10.016

Xuejing, W., Shuwen, Y., and Xiaobo, L. (2009). “Sol-gel preparation of CNT/ZnO nanocomposite and its photocatalytic property,” Chin. J. Chem. 27, 1317-1320. DOI: 10.1002/cjoc.200990220

Zak, A. K., Razali, R. M., Majid, W. A., and Darroudi, M. (2011). “Synthesis and characterization of a narrow size distribution of zinc oxide nanoparticles,” International Journal of Nanomedicine 6, 1399-1403. DOI: 10.2147/IJN.S19693

Zhai, J., Tao, X., Pu, Y., Zeng, X-F., and Chen, J-F. (2010). “Core/shell structured ZnO/SiO2 nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization and photocatalytic property,” Appl. Surf. Sci. 257, 393-397. DOI: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.06.091

Article submitted: August 19, 2020; Peer review completed: November 7, 2020; Revised version received and accepted: December 17, 2020; Published: January 13, 2021.

DOI: 10.15376/biores.16.1.1548–1560