Abstract

Effects of adding microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) and cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) were evaluated relative to the mechanical, thermal, morphological, and structural properties of rigid polyurethanes (rPUs). The composites were prepared with the blending of polyols/isocyanates and the cellulosic fillers at 0.25%, 0.5%, and 1% loadings. Scanning electron microscopic images showed that the samples had micro-scaled porosity, with cell sizes ranging from 250 to 800 nm. The fillers improved the mechanical strengths and modulus of neat rPUs due to the presence of the nano-sized cells in rPUs matrix. The addition of both fillers generally did not provide a positive effect on the thermal properties, and the weight loss generally increased while the loading rate of the fillers was increased from 0.25% to 1%. The samples had two small crystalline peaks at 18° and 19° according to the X-ray diffraction analysis. From the results, it can be said that the presence of both fillers generally improved all properties of the neat rPUs, and the effects of CNC on the properties were higher than MCC due to both lower particle size and the higher crystallinity of CNC.

Download PDF

Full Article

Effects of Cellulose Micro and Nanocrystals on the Mechanical, Thermal, Morphological, and Structural Properties of Rigid Polyurethanes

Ali İhsan Kaya,a Ömer Ümit Yalçın,a,* and Deniz Aydemir b

Effects of adding microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) and cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) were evaluated relative to the mechanical, thermal, morphological, and structural properties of rigid polyurethanes (rPUs). The composites were prepared with the blending of polyols/isocyanates and the cellulosic fillers at 0.25%, 0.5%, and 1% loadings. Scanning electron microscopic images showed that the samples had micro-scaled porosity, with cell sizes ranging from 250 to 800 nm. The fillers improved the mechanical strengths and modulus of neat rPUs due to the presence of the nano-sized cells in rPUs matrix. The addition of both fillers generally did not provide a positive effect on the thermal properties, and the weight loss generally increased while the loading rate of the fillers was increased from 0.25% to 1%. The samples had two small crystalline peaks at 18° and 19° according to the X-ray diffraction analysis. From the results, it can be said that the presence of both fillers generally improved all properties of the neat rPUs, and the effects of CNC on the properties were higher than MCC due to both lower particle size and the higher crystallinity of CNC.

DOI: 10.15376/biores.19.2.2842-2862

Keywords: Cellulose nanocrystals; Rigid polyurethanes; Porous materials; Material characterization

Contact information: a: Department of Forest Products Engineering, Isparta University of Applied Sciences, 32200, Isparta, Türkiye; b: Department of Forest Products Engineering, Faculty of Forestry, Bartin University, 74100, Bartın, Türkiye; *Corresponding author: omeryalcin@isparta.edu.tr

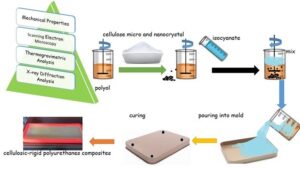

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Polyurethane consumption was approximately 18 million tons of production in 2016, and the global (PU) market has been predicted to reach 22.5 million tons in 2024 (Tran and Lee 2023). Polyurethanes (PUs) have many application areas, including construction, coatings, adhesives, and isolation foam materials (Latere Dwan’isa et al. 2004; Singh et al. 2020). They have been commonly used for isolation purposes due to low costs, and very low heat conductivity in the building industry. The PUs can be found in various forms, such as solid products, foams, paints, varnishes, adhesives, and impregnations (Niesiobędzka and Datta 2023). The rigid polyurethanes (rPUs), which are a type of highly cross-linked polymer, have been especially used in engineering applications including insulation materials in buildings, the automotive industry, and structural materials (Narine et al. 2007; Beltrán and Boyacá 2011). They are prepared by the reaction of polyisocyanate and polyol in the presence of a foaming agent (Wu et al. 2022). In general, PUs are produced through polymerization between the isocyanate functional groups of the isocyanate and the hydroxyl groups of the polyol (Gama et al. 2018), as depicted in Fig. 1. The properties of PUs are highly dependent on the type and properties of the polyol (Singh et al. 2020). Polyols are mostly used in the molecular weight (Mw) range from 200 to 8000 g/mol-1 in the production of PUs (Hu et al. 2014). The rPUs exhibit good performance with good properties of low-temperature insulations, and they have in the usage area including refrigerated vehicles, rail tankers, vessels in transportation cabinets, pipelines, liquid gas tanks, etc. (Demharter 1998). It was tried to improve the properties with compatibilizers such as an alkyl maleic anhydride, etc. (Savani et al. 2023) and by reinforcing with organic or inorganic fillers (Alves et al. 2022, Kaya 2022). However, polyols generally are synthetic-based materials. Therefore, to provide the sustainability of the rPUs, renewable resources including cellulose, lignin, or chitin to partially or completely replace the synthetic polyols have been investigated in various scientific studies (Aydemir et al. 2011; Antunes et al. 2014; Głowinska and Datta 2016; Zhou et al. 2016; Septevani et al. 2017; Kustiyah et al. 2019).

Fig. 1. Formation of polyurethanes from polyol and isocyanate (Hu et al. 2014)

Cellulose, one of the most abundant biopolymers in the world, is a renewable resource (Bondeson et al. 2006) that has been commonly used in various industries including papermaking, food, optics, and pharmaceuticals due to its abundant availability and low prices, besides its physical and chemical features (de Souza Lima and Borsali 2004; Qi et al. 2009). The cellulose can be produced as micro or nano-sized particles. Recent advances in material science and the usage areas of cellulose have expanded due to its superior properties and production costs (Rueda et al. 2013). Cellulose nanocrystals (CNC), produced from cellulose fibers, are nano-sized, renewable, and biologically degradable materials. Therefore, they can be used as reinforcing agents in the plastic industry as a green and eco-friendly material (George and Sabapathi 2015). Hence, the demands for CNC have increased in the materials and polymers societies (Habibi et al. 2010). It was indicated that CNC as nanofillers improved tensile strength, thermal stability, water resistance, and anti-yellowing properties of waterborne polyurethanes (Liu et al. 2013; She et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014). In contrast, using a sustainable nanomaterial should be evaluated to increase thermal and mechanical performance (Septevani et al. 2018). Meanwhile, polyurethanes are a type of polymer that is used for a variety of applications, which are biomedicine, coatings, foams, composites (Seydibeyoglu and Oksman 2008), adhesives, applications (Liu et al. 2013) on automobiles for external polish, advanced color retention, and in structures where steel supports and concrete reinforces (Chattopadhyay and Raju 2007). Zhou et al. (2016) reported that water-blown bio-polyurethane (BPU) foams based on palm oil were developed. The physical properties were impacted by the reactive functional groups present on the nano-silica surface. Due to the thermal barrier properties of nano-silica, the thermal stability of nano-filled foams was enhanced. Furthermore, in modified nano silica-contained samples, the boundary layer’s covalent bond creation enhanced the samples’ static mechanical capabilities (Nikje and Tehrani 2010).

The addition of CNC generally increased the compressive strength values, dimensional stability, and rigidity, and it decreased deformation resilience. It has been reported that a reduction of 5% thermal conductivity of rPUs foam was achieved by adding a very low CNC fraction with an optimized solvent-free ultra-sonication method and adding 0.4 wt% of CNC without any modification (Septevani et al. 2017). It was studied that various CNC contents were incorporated in high crystalline bio-based PUs with various proportions by solvent casting procedure, and mechanical properties, such as thermomechanical and tensile strength, increased (Saralegi et al. 2013). The addition of CNC had an impact on the solid Pus’ characteristics as well; in the 0.5 wt% CNC composite, the tensile modulus was significantly higher than in the unfilled solid polyurethane (Wik et al. 2011). The tensile strength and modulus of the bio-based PU blend with acetylated cellulose nanocrystals (ACNC) generally increased at low percentages with the addition of the filler. When ACNC loading increased from 0 wt% to 10 wt%, the elongation at the break of the PU blends reached more than twice that of polyurethane (Lin et al. 2013). The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of cellulosic micro/nanomaterials at low percentages (0.25%, 0.5%, and 1%) on the mechanical, thermal, morphological, and structural properties of rPUs. The effects of particle size of the fillers were also assessed.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Polyols and isocyanates used in the preparation of rPUs were supplied from Osa Chemical Company Co., Ltd., (Istanbul, Turkiye). Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany) in powder form at 20 μm particle size, as shown in Fig. 2 (a). Cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) were obtained with acid hydrolysis, as explained by Aydemir et al. (2023). The dimensions of CNC were 15 to 30 nm (width) and 150 to 200 nm (length), as shown in Fig. 2 (b). Both materials were dried in an oven at 50 °C for a few days prior to processing.

Fig. 2. SEM images of the fillers used including MCC (a) and CNC (b).

Preparation of cellulosic-rPUs composites

Polyurethane was produced by mixing polyol and isocyanates (1:1 wt%) according to the manufacturer’s advice and following Hassan and Rus (2014) with the one-shot method. The materials used for producing rPU were polyester polyol (PES240®) having a hydroxyl value (260 mgKOH-1), viscosity (cone plate) (25 ℃) 3500 mPa.s, density 1.10 g/cm-3, and MDI (ISONAT 2000®) (methylene diphenyl diisocyanate) with – NCO content 33.4 %, viscosity 2500 mPa.s (25℃), and density 1.25 g/cm-3. Both materials were taken in a piston cylinder apparatus, and they were blended at 1500 rpm for 2 min. to provide a homogenous mixture. After the blending process, the mixture was casted into silicon molds to obtain the standard test specimens according to ASTM D638-03 (2001) Type I for the tensile test and ASTM D790-03 (2003) for the flexure test. This sample was labelled as neat PU (NPU). The PU blends were prepared with MCC and CNC at 0.25%, 0.5%, and 1% wt. Firstly, the fillers including MCC and CNC were added to polyols and blended at 1500 rpm for 5 min. After the blending, isocyanates were added to polyols-filler blends. The blends were casted to a silicon mold with a dimension of 10 mm × 100 mm × 200 mm (T × W × L). In the literature review, scientific studies showed that the addition of CNC at high percentages (>1%) to polymer matrices can cause aggregation, and such a status can be responsible for low mechanical properties. Therefore, the low loading ratio of CNC was selected.

The processing temperature and time for the polymerization reaction were at 20 ± 5 °C and 2 h, respectively. All reaction processes were conducted in a cabinet with vacuum (20 to 30 mmHg) to avoid air bubbles. The panels were moved from the mold, and they were kept a climatic cabinet for curing at 60 °C for 24 h. Table 1 shows the formulations of the samples.

Table 1. Formulations of the Samples

Methods

An Utest mechanical tester was used to characterize the neat PU and the PU composites. Tensile tests were conducted on samples with a dimension of 3.2 mm × 13 mm × 165 mm (T × W × L) according to ASTM D638-03 (2001) Type I, and the test speed was selected as 5 mm/min. Elongation during the test was measured with an extensometer and it was also used to find tensile modulus. Tensile strength and modulus were calculated as given below;

(1)

where F is the fracture force (N), a and b are the width and highness of the sample, A is the area of the sample (mm2), L is the length of the samples (mm), and ΔL is the change in the length.

Flexural tests were conducted on a sample with a dimension of 3.2 mm × 12.7 mm × 125 mm (T × W × L) with a mechanical tester at a test speed of 1.27 mm/min and support range of 50.8 mm according to ASTM D790-03 (2003). Seven specimens for all the formulations were tested and the arithmetic averages were used. Flexural strength and modulus were calculated according to Eq. 2,

(2)

where w is the width of the sample (mm), h is the height of the samples (mm), d is the deflection (mm), and L is the length of the samples (mm).

Scanning electron microscopy

Morphological characterization was conducted with Tescan MAIA3 XMU (Brno, Czech Republic) with a voltage of 5 to 10 kV. The fractured section of tensile samples (Tescan, SEM/STEM, Prague, Czech) were coated with a mixture of palladium/gold to improve the electron flowing before SEM characterization. The aspect ratio (r) of the cells in the samples was determined with width (w) divided by height (h) according to SEM images.

Thermogravimetric analysis

Thermal stability of neat rPUs and the rPU composites was conducted using about 1.0 to 2 mg of samples at a heat scale from 25 to 800 °C, at the rate of 20 °C/min under nitrogen, and a nitrogen flow ratio of 20 mL/min with a Hitachi STA 7300 thermal analyzer (Chiyoda, Japan). The temperatures in weight loss at 10% (T10%) and 50% (T50%), maximum derivative thermal gravimetry (DTGmax), and total weight loss (WL) values were determined with the TGA curves.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

The XRD patterns of the samples were determined with an X-ray diffractometer (Model XPert PRO, Philips PANalytical, Netherlands) with Ni-filtered Cu Kα (1.540562 Å) radiation resource at a scale from 5° to 80° 2θ range. A silicon zero frame plate was used to ensure there were no peaks related to the sample holder. The crystallinity index (CI) of neat rPU and the PU composites were determined with the OriginLab Pro 2024 software trial version using the equation as given below,

(3)

where Ac is the combined area under the respective crystal peaks, and Aa is the combined area of the amorphous halo.

Statistical analysis

One-way variance analysis (ANOVA) and the Duncan test were conducted at the level of significance 95% (p < 0.05) with the SPSS ver. 22.0 software (Armonk, NY, USA). The groups that were statistically significant were indicated by different letters A, B, C, etc.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mechanical properties and stress-strain graph during tensile test of neat rPU and the PU composites are shown in Figs. 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

Fig. 3. Flexural results of neat PU and the PU composites

The mechanical properties of neat rPU improved with the presence of the fillers. While the filler loading increased from 0.25% to 1%, as given in Fig. 3, both the flexural strength and flexural modulus for all the rPU composites significantly increased. However, the flexure strength slightly decreased for 0.25% MCC due to the possible aggregation of the MCC particles, as determined by Gorbunova et al. (2023). The maximum and minimum increasing percentages in the flexural strength were determined as 47.1% for the rPU composites with 1% and 15.5% CNC for the PU composites with 0.25% MCC, respectively. The presence of the fillers had a positive effect on the flexural modulus of the samples, and the maximum flexural modulus was found to be 1.3 GPa (an improvement rate of 62.5%) for the rPU composites with 1% MCC and 1% CNC. These results can be explained by the presence of CNCs that were tightly incorporated into the polymer-based matrix and an increase of the interpenetration level of the polymer network. This status may be responsible for the increase in the strength and ductility of the rPU composites. Similar results were found to be due to the good distribution of nanoparticles in the matrix increases the interfacial area with the effect of hydrogen bonding and strengthens the bonds, resulting in a synergistic effect by Dos Santos (2017), Li et al. (2019), and Bi et al. (2020).

Figure 4 shows the tensile strength (TS) and tensile modulus (TM) of neat PU and the PU composites. The addition of the fillers ranging from 0.25% to 1% generally increased both TS and TM. The TS was determined to improve at a range from 2.8% (18.3 MPa in rPU composites with 0.25% CNC) to 81.5% (32.3 MPa in rPU composites with 1% CNC) with the presence of the fillers due to better compatibility between CNC and the PU matrix as presented by Gorbunova et al. (2023). The TM of the rPU composites was higher than neat rPU, and the maximum tensile modulus was found as 1.1 GPa (an improvement of 37.5%) for the PU composites with 0.25% MCC, 0.5% CNC, and 1% CNC. However, the high percentage of MCC generally decreased both tensile strength and tensile modulus. This effect was attributed to MCC particle aggregation during solvent casting as determined by Choi et al. (2023). As a result, both flexural and tensile results enhanced with the addition of both the fillers, and the effects of CNC on the mechanical properties were higher than that of MCC due to both lower particle size and the higher crystallinity of CNC as presented in dos Santos et al. (2017).

Fig. 4. Tensile results of neat PU and the PU composites

Fig. 5. Stress-strain graph during tensile test of neat rPU and the rPU composites

The effects of adding MCC and CNC to the PU matrix on tensile strength and tensile modulus leads to strong interactions between the fillers and between the filler and the matrix, restricting the movement of the matrix (Cao et al. 2007).

One-way variance analysis was conducted to determine whether the changes in the mechanical properties were statistically different at 95% significant level. Duncan tests were performed to detect the changes among which groups were significant, and then the results are shown with letters A, B, C, etc. According to the statistical analysis, the changes in the rPU composites with the fillers were statistically significant, and here it can be said that the presence of both MCC and CNC generally increased the mechanical properties. Stress-strain graph during tensile test of neat rPU and the rPU composites can be seen in Fig. 5, and it can be said that the addition of the fillers generally increased the elongation at break of neat PU. The maximum elongation at break was about 5% for the PU composites with 0.25% MCC. However, the addition of 1% MCC to neat rPU decreased the elongation at break of the rPU composites. From here, it can be said that CNC have higher effect on the elongation at break of neat PU due to the difference in the size of CNC and MCC particles affecting the change in the level of interactions between neat rPU macromolecules and high crystallinity of CNC compared to MCC.

The addition of MCC and CNC provided a porous structure with micro-scaled cell size according to the morphological characterization, and the status generally increased the mechanical properties of the samples. SEM images and the cell sizes of neat rPU and the rPU composites with MCC and CNC are shown in Figs. 6, 7, and 8.

Fig. 6. Cell Size of neat rPU and the rPU composites

It is apparent that the rPU composites had a homogenous porous structure. The neat rPU had average cell diameters of about 565 nm (at a range from 110 nm to 992 nm). The average cell diameters were about 495, 486, and 409 nm (a range from 142 nm to 810 nm) for the rPU composites with 0.25%, 0.5%, and 1% MCC, respectively, whereas the average cell diameter generally was about 730, 740, and 798 nm for the rPU composites with 0.25%, 0.5%, and 1% CNC, respectively. As a result, SEM images exhibited that the adding MCC provided smaller cell diameter than the adding CNC. All the samples had almost similar cellular structures, but the cell diameter of the PU composites was larger. Amran et al. (2019) found that reinforcement of rigid polyurethane with lignocellulosic biomass resulted in a porous structure, and the cells ranged from 785 to 650 nm. In another study, it was found that the addition of cellulosic filler to rPU generally decreased the cell size from 464 ± 126 µm to 228 ± 81 µm (Silva et al. 2010). It is generally said that foams with higher cell density produced higher strength and modulus (Amran et al. 2019; Lubczak et al. 2022), whereas in this study, the cell size was generally homogenous with uniform cell diameters. Other studies have found that the small-sized cells in the porous structures provided good features, and the size effect supported the increases in the mechanical properties. Thus, it can be said that such a status has a positive effect on the mechanical properties of the rPU and the PU composites (Aydemir et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2022).

Fig. 7. SEM images of neat PU and the PU composites with different ratios of MCC, NPU (a), 0.25% MCC (b), 0.5 MCC (c), and 1% MCC (d)

Fig. 8. SEM images of neat PU and the PU composites with different ratios of CNC NPU (a), 0.25% CNC (b), 0.5 CNC (c), and 1% CNC (d)

The shape and diameters of the cells and the cell density in the porous materials generally have an effect on thermal properties, and therefore, thermal studies were conducted on the neat rPU and the rPU composites. Both TGA and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves showing the thermal degradation behavior of the neat rPU and the rPU composites are provided in Figs. 9 and 10, and also in Table. 2. The TGA (Fig. 9) and DTG curves (Fig. 10) reveal the decomposition stages of neat rPU and the rPU prepared with CNC and MCC. Thermal decomposition started from the weakest link forming the polyurethane structure (Yang et al. 1986).

The thermal decomposition curve of the rPU disappeared at 80 to 120 °C, due to the removal of moisture and inorganic compounds, and the initial weight loss occurred below 160 °C (Wu et al. 2023). Then there was a complicated mechanism consisting of a few decomposition steps at 200 to 320 °C, which was attributed to the separation in urethane groups (Somani et al. 2003; Mosiewicki et al. 2009; Raghu et al. 2009). There was initial decomposition into polyol and isocyanate components, followed by thermal decomposition leading to the formation of amines, minor transition components, and carbon dioxide (Somani et al. 2003; Tanaka et al. 2008; Raghu et al. 2009; Kirbaş 2022). The third separation step proceeded more slowly and separation of the hard segments takes place at 250 to 350 °C and 370 to 420 °C (Marcovich et al. 2001; Gibson 2003). The stage above 250 to 300 °C might be attributed to thermal degradation and decomposition of cellulose (D’Acierno et al. 2020). The DTG curves showed two DTGmax peaks due to degradation and decomposition of both cellulose and rPUs, as can be seen in Fig. 10. The neat rPU showed a different behavior in DTG curves, and this status can be explained that this is probably the result of the degradation of the residual unreacted polyol component. In addition, the degradation rate of the NPU at 343 °C is only slightly lower than the degradation rate at 389 °C, which is related to the degradation of the flexible segments (Kebir et al. 2006, Hirzin et al. 2018).

Fig. 9. TG curves of neat rPU and the rPU composites

Fig. 10. DTG curves of neat rPU and the rPU composites

The extent of decomposition and summary of the decomposition process of the neat rPU, whose thermal stability was changed by the addition of MCC and CNC, are given in Table 2. When the thermal decomposition were examined, it was observed that as the amount of both MCC and CNC increased, the T10% and T50% values corresponding to weight loss generally decreased from 98% to 92%. Therefore, the increment in additive amounts, degradation temperatures increased and weight loss decreased. Similarly, while the addition of CNC increased, weight loss continuously decreased. The lowest weight loss was 92% (decrease rate of 6%) for the PU composites with 1% CNC and 94% (decrease rate of 4%) for the PU composites with 1% MCC. On this basis, it can be said that there was a decrease in weight loss with the presence of MCC and CNC. The decrease in the weight loss caused due to the degradation at high temperatures of polymer matrix and the fillers. Similar results were also seen with the addition of different additives to PU (Saha et al. 2008; Semenzato et al. 2009). According to the results, it is suggested that the thermal degradation of the rPU composites with MCC and CNC is slower than the rPUs. Similar results have been seen in the literature (Guo and Petrovic 2000; Latere Dwan’isa et al. 2004; Pashaei et al. 2010; Luo et al. 2012; Kaya 2022). It was found that the rPU composites with MCC and CNC needs more energy for decomposition than the rPUs. These results suggest that MCC and CNC have an effect that inhibits heat dissipation and limits further degradation (Marcovich et al. 2006; Luo et al. 2012; Aydemir et al. 2023). According to this result, it can be stated that MCC and CNC seem to be a heat barrier to prevent weight loss (Teipel et al. 2016; Aydemir and Gardner 2020).

Table 2. Results of the Thermogravimetric Analysis of Neat PU and the PU Composites

The XRD pattern of neat rPU and the rPU composites is shown in Fig. 11. The rPU composites are represented by a peak at around 19.5° in the XRD graph. The XRD patterns are similar to each other, but there are differences among the curves of the samples due to the addition of micro and nano crystalline cellulose.

Fig. 11. XRD pattern of neat PU and the PU composites

The crystallinity of the polymers affects the mechanical properties, and several studies showed that the crystallinity positively affects the mechanical properties of polymers (Aydemir et al. 2015; Simmons et al. 2019). Previous studies showed that the intense crystalline peaks at 5 to 40° for rPU were determined, and the crystallinity was measured at range from 30% to 50% (Trovati et al. 2010, Popescu et al. 2013, Alves et al. 2022). Both MCC and CNC, as used in this study, can be regarded as highly crystalline fillers. The crystallinity was calculated to determine how the crystallinity of rigid PU will be affected with the presence of such fillers, as shown in Table 3. Neat PU and the PU composites exhibited one crystalline peak at around 19.5° in the XRD graph. The crystallinity of neat PU and the PU composites were calculated using the area between 15° and 25° with mathematical software to determine the effects of the cellulosic fillers on the crystallinity of neat rPU. As shown in Tables 3, 2θ changed at a range from 19.1° to 19.5°. The crystallinity increased with the presence of the fillers. With increasing filler loading, the crystallinity generally increased. The highest crystallinity was calculated as 56.3% for the PU composites with 1% MCC and the PU composites with 0.5% MCC followed with the crystallinity index of 49.8%.

Table 3. Crystallinity and 2θ°of Neat rPU and the rPU Composites

CONCLUSIONS

- The recycled polyurethane (rPU) was successfully blended with microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) and cellulose nanocrystals (CNC). Both fillers provided good interaction in the rPU matrix, and in this way, the usage application areas of rPU can be raised with the presence of cellulosic materials.

- The mechanical properties increased with addition of the fillers due to better morphological structure and micro-sized cells between the fillers and neat PU as revealed by the morphological characterization.

- Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis showed that the samples had small-sized cells under generally one µm, and the MCC was found to provide the smaller cells in the rPU matrix than CNC.

- Thermal behavior of the rPU composites generally was similar with the neat rPU, and thermal stability of the neat rPU was improved with the addition of fillers, whereas the weight loss decreased with the presence of the fillers.

- The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were similar to each other, and the crystallinity generally increased with addition of the fillers. From the results, it can be said that both the fillers generally improved the properties and the morphological structure of the neat rPUs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors declare that there is no financial support and no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES CITED

Alves, L. R. S. T., Alves, M. D. T. C., Honorio, L. M. C., Moraes, A. I., Silva-Filho, E. C., Peña-Garcia, R., Furtini, M. B., da Silva, D. A., and Osajima, J. A. (2022). “Polyurethane/vermiculite foam composite as sustainable material for vertical flame retardant,” Polymers 14(18), article 3777.

Amran, U. A., Zakaria, S., Chia, C. H., Roslan, R., Jaafar, S. N. S., and Salleh, K. M. (2019). “Polyols and rigid polyurethane foams derived from liquefied lignocellulosic and cellulosic biomass,” Cellulose 26, 3231-3246. DOI:10.1007/s10570-019-02271-w

Antunes, M. D. S. P., Cano, Á., Redondo Realinho, V. C. D., Arencón Osuna, D., and Velasco Perero, J. I. (2014). “Compression properties and cellular structure of polyurethane composite foams combining nanoclay and different reinforcements,” International Journal of Composite Materials 4(5A), 27-34. DOI: 10.5923/j.cmaterials.201401.04

Aydemir, D., and Gardner, D. J. (2020). “The effects of cellulosic fillers on the mechanical, morphological, thermal, viscoelastic, and rheological properties of polyhydroxybutyrate biopolymers,” Polymer Composites 41(9), 3842-3856. DOI: 10.1002/pc.25681

Aydemir, D., Kiziltas, A., Gardner, D. J., Han, Y., and Gunduz, G. (2011). “Foaming of cellulose nanofibril-reinforced SMA composites,” in: TAPPI International Conference on Nanotechnology for Renewable Materials, Crystal City, Arlington, VA, USA, pp. 32-43.

Aydemir, D., Kiziltas, A., Kiziltas, E. E., Gardner, D. J., and Gunduz, G. (2015). “Heat treated wood–nylon 6 composites,” Composites Part B: Engineering 68, 414-423. DOI: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.08.040

Aydemir, D., Sözen, E., Borazan, I., Gündüz, G., Ceylan, E., Gulsoy, S. K., Kılıç-Pekgözlü, A., and Bardak, T. (2023). “Electrospinning of PVDF nanofibers incorporated cellulose nanocrystals with improved properties,” Cellulose 30(2), 885-898. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-022-04948-1

Beltrán, A. A., and Boyacá, L. A. (2011). “Production of rigid polyurethane foams from soy-based polyols,” Latin American Applied Research 41(1), 75-80.

Bi, H., Ren, Z., Ye, G. et al. (2020). “Fabrication of cellulose nanocrystal reinforced thermoplastic polyurethane/polycaprolactone blends for three-dimension printing self-healing nanocomposites,” Cellulose 27, 8011-8026. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-020-03328.

Bondeson, D., Mathew, A., and Oksman, K. (2006). “Optimization of the isolation of nanocrystals from microcrystalline cellulose by acid hydrolysis,” Cellulose 13, 171-180. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-006-9061-4

Cao, X., Dong, H., and Li, C. M. (2007). “New nanocomposite materials reinforced with flax cellulose nanocrystals in waterborne polyurethane,” Biomacromolecules 8(3), 899-904.

Chattopadhyay, D. K., and Raju, K. V. S. N. (2007). “Structural engineering of polyurethane coatings for high performance applications,” Progress in Polymer Science 32(3), 352-418. DOI: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.05.003

Choi, S. M., Lee, S. Y., Lee, S., Han, S. S., and Shin, E. J. (2023). “In situ synthesis of environmentally friendly waterborne polyurethane extended with regenerated cellulose nanoparticles for enhanced mechanical performances,” Polymers 15(6), article 1541.

D’Acierno, F., Hamad, W. Y., Michal, C. A., and MacLachlan, M. J. (2020). “Thermal degradation of cellulose filaments and nanocrystals,” Biomacromolecules 21(8), 3374-3386. DOI: 10.1021/acs.biomac.0c00805

De Souza Lima, M. M., and Borsali, R. (2004). “Rodlike cellulose microcrystals: Structure, properties, and applications,” Macromolecular Rapid Communications 25(7), 771-787. DOI: 10.1002/marc.200300268

Dos Santos, F. A., Iulianelli, G. C., and Tavares, M. I. (2017). “Effect of microcrystalline and nanocrystals cellulose fillers in materials based on PLA matrix,” Polymer Testing 61, 280-288. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2017.05.028

Feng, B., Fang, X., Wang, H. X., Dong, W., and Li, Y. C. (2016). “The effect of crystallinity on compressive properties of Al-PTFE,” Polymers 8(10), article 356. DOI: 10.3390/polym8100356

Gama, N. V., Ferreira, A., and Barros-Timmons, A. (2018). “Polyurethane foams: Past, present, and future,” Materials 11(10), article 1841. DOI: 10.3390/ma11101841

George, J., and Sabapathi, S. N. (2015). “Cellulose nanocrystals: Synthesis, functional properties, and applications,” Nanotechnology, Science and Applications 2015, 45-54. DOI: 10.2147/NSA.S64386

Gibson, L. J. (2003). “Cellular solids,” MRS Bulletin 28(4), 270-274. DOI: 10.1557/mrs2003.79

Głowińska, E., and Datta, J. (2016). “Bio polyetherurethane composites with high content of natural ingredients: Hydroxylated soybean oil based polyol, bio glycol and microcrystalline cellulose,” Cellulose 23, 581-592. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-015-0825-6

Gorbunova, M., Grunin, L., Morris, R. H., and Imamutdinova, A. (2023). “Nanocellulose-based thermoplastic polyurethane biocomposites with shape memory effect,” Journal of Composites Science 7(4), article 168. DOI: 10.3390/jcs7040168

Guo, A., Javni, I., and Petrovic, Z. (2000). “Rigid polyurethane foams based on soybean oil,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science 77(2), 467-473.

Habibi, Y., Lucia, L. A., and Rojas, O. J. (2010). “Cellulose nanocrystals: Chemistry, self-assembly, and applications,” Chemical Reviews 110(6), 3479-3500. DOI: 10.1021/cr900339w

Hassan, N. N. M., and Rus, A. Z. M. (2014). “Acoustic performance of green polymer foam from renewable resources after UV exposure,” International Journal of Automotive and Mechanical Engineering 9, 1639-1648. DOI: 10.15282/ijame.9.2013.14.0136

Hirzin, R. S. F. N., Azzahari, A. D., Yahya, R., Hassan, A., and Tahir, H. (2018). “The behavior of semi-rigid polyurethane film based on functionalized rubber by one-shot and two-shot method preparation,” Journal of Materials Science 53, 13280-13290.

Hu, S., Luo, X., and Li, Y. (2014). “Polyols and polyurethanes from the liquefaction of lignocellulosic biomass,” ChemSusChem 7(1), 66-72. DOI: 10.1002/cssc.201300760

Kaya, A. I. (2022). “Determination of chemical structure, mechanical properties and combustion resistance of polyurethane doped with boric acid,” Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 35(5), 720-739. DOI: 10.1177/08927057211019444

Kebir, N., Campistron, I., Laguerre, A., Pilard, J.-F., Bunel, C., and Couvercelle, J.-P. (2006). “Use of new hydroxytelechelic cis-1, 4-polyisoprene (HTPI) in the synthesis of polyurethanes (PUs): Influence of isocyanate and chain extender nature and their equivalent ratios on the mechanical and thermal properties of Pus,” e-Polymers 6(1), article 048. DOI: 10.1515/epoly.2006.6.1.619

Kirbaş, İ. (2022). “Investigation of the internal structure, combustion, and thermal resistance of the rigid polyurethane materials reinforced with vermiculite,” Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 35(10), 1561-1575. DOI: 10.1177/0892705720939152

Kustiyah, E., Setiaji, D. A., Nursan, I. A., Syahidah, W. N., and Chalid, M. (2019). “Comparison study on morphology and mechanical properties of starch, lignin, cellulose–based polyurethane foam,” in: AIP Conference Proceedings 2175(1), article ID 020061. DOI: 10.1063/1.5134625

Latere Dwan’isa, J. P., Mohanty, A. K., Misra, M., Drzal, L. T., and Kazemizadeh, M. (2004). “Biobased polyurethane and its composite with glass fiber,” Journal of Materials Science 39, 2081-2087. DOI: 10.1023/B:JMSC.0000017770.55430.fb

Li, K., Jin, S., Li, J., and Chen, H. (2019). “Improvement in antibacterial and functional properties of mussel-inspired cellulose nanofibrils/gelatin nanocomposites incorporated with graphene oxide for active packaging,” Ind. Crop. Prod. 132, 197-212.

Lin, S., Huang, J., Chang, P. R., Wei, S., Xu, Y., and Zhang, Q. (2013). “Structure and mechanical properties of new biomass-based nanocomposite: Castor oil-based polyurethane reinforced with acetylated cellulose nanocrystal,” Carbohydrate Polymers 95(1), 91-99. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.02.023

Liu, H., Cui, S., Shang, S., Wang, D., and Song, J. (2013). “Properties of rosin-based waterborne polyurethanes/cellulose nanocrystals composites,” Carbohydrate Polymers 96(2), 510-515. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.04.010

Lubczak, J., Lubczak, R., Chmiel-Bator, E., and Szpiłyk, M. (2022). “Polyols and polyurethane foams obtained from mixture of metasilicic acid and cellulose,” Polymers14(19), article 4039. DOI: 10.3390/polym14194039

Luo, X., Mohanty, A., and Misra, M. (2012). “Water-blown rigid biofoams from soy-based biopolyurethane and microcrystalline cellulose,” Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 89, 2057-2065. DOI: 10.1007/s11746-012-2100-4

Marcovich, N. E., Aranguren, M. I., and Reboredo, M. M. (2001). “Modified woodflour as thermoset fillers. Part I. Effect of the chemical modification and percentage of filler on the mechanical properties,” Polymer 42(2), 815-825. DOI: 10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00286-X

Marcovich, N. E., Auad, M. L., Bellesi, N. E., Nutt, S. R., and Aranguren, M. I. (2006). “Cellulose micro/nanocrystals reinforced polyurethane,” Journal of Materials Research 21(4), 870-881. DOI: 10.1557/jmr.2006.0105

Mosiewicki, M. A., Dell’Arciprete, G. A., Aranguren, M. I., and Marcovich, N. E. (2009). “Polyurethane foams obtained from castor oil-based polyol and filled with wood flour,” Journal of Composite Materials 43(25), 3057-3072. DOI: 10.1177/0021998309345342

Narine, S. S., Kong, X., Bouzidi, L., and Sporns, P. (2007). “Physical properties of polyurethanes produced from polyols from seed oils: II. Foams,” Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 84, 65-72. DOI: 10.1007/s11746-006-1008-2

Niesiobędzka, J., and Datta, J. (2023). “Challenges and recent advances in bio-based isocyanate production,” Green Chemistry 25, 2482-2504. DOI: 10.1039/D2GC04644J

Nikje, M. M. A., and Tehrani, Z. M. (2010). “Thermal and mechanical properties of polyurethane rigid foam/modified nanosilica composite,” Polymer Engineering and Science 50(3), 468-473. DOI: 10.1002/pen.21559

Pashaei, S., Siddaramaiah, and Syed, A. A. (2010). “Thermal degradation kinetics of polyurethane/organically modified montmorillonite clay nanocomposites by TGA,” Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A: Pure and Applied Chemistry 47(8), 777-783. DOI: 10.1080/10601325.2010.491756

Qi, H., Cai, J., Zhang, L., and Kuga, S. (2009). “Properties of films composed of cellulose nanowhiskers and a cellulose matrix regenerated from alkali/urea solution,” Biomacromolecules 10, 1597-1602. DOI: 10.1021/bm9001975

Raghu, A. V., Gadaginamath, G. S., Jeong, H. M., Mathew, N. T., Halligudi, S. B., and Aminabhavi, T. M. (2009). “Synthesis and characterization of novel Schiff base polyurethanes,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science 113(5), 2747-2754. DOI: 10.1002/app.28257

Rueda, L., Saralegui, A., d’Arlas, B. F., Zhou, Q., Berglund, L. A., Corcuera, M. A., Mondragon, I., and Eceiza, A. (2013). “Cellulose nanocrystals/polyurethane nanocomposites. Study from the viewpoint of microphase separated structure,” Carbohydrate Polymers 92(1), 751-757. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.09.093

Saha, M. C., Kabir, M. E., and Jeelani, S. (2008). “Enhancement in thermal and mechanical properties of polyurethane foam infused with nanoparticles,” Materials Science and Engineering: A 479(1-2), 213-222. DOI: 10.1016/j.msea.2007.06.060

Saralegi, A., Rueda, L., Martin, L., Arbelaiz, A., Eceiza, A., and Corcuera, M. A. (2013). “From elastomeric to rigid polyurethane/cellulose nanocrystal bionanocomposites,” Composites Science and Technology 88, 39-47. DOI: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2013.08.025

Savani, N. G., Naveen, T., and Dholakiya, B. Z. (2023). “A review on the synthesis of maleic anhydride based polyurethanes from renewable feedstock for different industrial applications,” Journal of Polymer Research 30(5), 1-26.

Semenzato, S., Lorenzetti, A., Modesti, M., Ugel, E., Hrelja, D., Besco, S., Michelin, R. A., Sassi, A., Facchin, G., Zorzi, F., et al. (2009). “A novel phosphorus polyurethane FOAM/montmorillonite nanocomposite: Preparation, characterization and thermal behaviour,” Applied Clay Science 44(1-2), 35-42. DOI: 10.1016/j.clay.2009.01.003

Septevani, A. A., Evans, D. A., Annamalai, P. K., and Martin, D. J. (2017). “The use of cellulose nanocrystals to enhance the thermal insulation properties and sustainability of rigid polyurethane foam,” Industrial Crops and Products 107, 114-121. DOI: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.05.039

Septevani, A. A., Evans, D. A., Martin, D. J., and Annamalai, P. K. (2018). “Hybrid polyether-palm oil polyester polyol based rigid polyurethane foam reinforced with cellulose nanocrystal,” Industrial Crops and Products 112, 378-388. DOI: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.12.032

Seydibeyoglu, M. O., and Oksman, K. (2008). “Novel nanocomposites based on polyurethane and micro fibrillated cellulose,” Composites Science and Technology 68, 908-914. DOI: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.08.008

She, Y., Zhang, H., Song, S., Lang, Q., and Pu, J. (2013). “Preparation and characterization of waterborne polyurethane modified by nanocrystalline cellulose,” BioResources 8(2), 2594-2604. DOI: 10.15376/biores.8.2.2594-2604

Silva, M. C., Takahashi, J. A., Chaussy, D., Belgacem, M. N., and Silva, G. G. (2010). “Composites of rigid polyurethane foam and cellulose fiber residue,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science 117(6), 3665-3672. DOI: 10.1002/app.32281

Simmons, H., Tiwary, P., Colwell, J. E., and Kontopoulou, M. (2019). “Improvements in the crystallinity and mechanical properties of PLA by nucleation and annealing,” Polymer Degradation and Stability 166, 248-257. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2019.06.001

Singh, I., Samal, S. K., Mohanty, S., and Nayak, S. K. (2020). “Recent advancement in plant oil derived polyol‐based polyurethane foam for future perspective: A review,” European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 122(3), article ID 1900225. DOI: 10.1002/ejlt.201900225

Somani, K. P., Kansara, S. S., Patel, N. K., and Rakshit, A. K. (2003). “Castor oil based polyurethane adhesives for wood-to-wood bonding,” International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 23(4), 269-275. DOI: 10.1016/S0143-7496(03)00044-7

Tanaka, R., Hirose, S., and Hatakeyama, H. (2008). “Preparation and characterization of polyurethane foams using a palm oil-based polyol,” Bioresource Technology 99(9), 3810-3816. DOI: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.007

Teipel, B. R., Vano, R. J., Zahner, B. S., Teipel, E. M., Chen, I. C., and Akbulut, M. (2016). “Nanocomposites of hydrophobized cellulose nanocrystals and polypropylene,” MRS Advances 1(10), 659-665. DOI: 10.1557/adv.2016.88

Tran, M. H., and Lee, E. Y. (2023). “Production of polyols and polyurethane from biomass: A review,” Environmental Chemistry Letters 2023, 1-25. DOI: 10.1007/s10311-023-01592-4

Trovati, G., Sanches, E. A., Neto, S. C., Mascarenhas, Y. P., and Chierice, G. O. (2010). “Characterization of polyurethane resins by FTIR, TGA, and XRD,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science 115(1), 263-268.

Popescu, L. M., Rusti, C. F., Piticescu, R. M., Buruiana, T., Valero, T., and Kintzios, S. (2013). “Synthesis and characterization of acid polyurethane–hydroxyapatite composites for biomedical applications,” Journal of Composite Materials 47(5), 603-612. DOI: 10.1177/0021998312443396

Wang, C., Huang, H., Zhang, Z., Zhang, L., Yan, J., and Ren, L. (2022). “Formation, evolution and characterization of nanoporous structures on the Ti6Al4V surface induced by nanosecond pulse laser irradiation,” Materials & Design 223, Article ID 111243. DOI: 10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111243

Wik, V. M., Aranguren, M. I., and Mosiewicki, M. A. (2011). “Castor oil‐based polyurethanes containing cellulose nanocrystals,” Polymer Engineering & Science 51(7), 1389-1396. DOI: 10.1002/pen.21939

Wu, J., Zhang, X., Qin, Z., Zhang, W., and Yang, R. (2023). “Inorganic/organic phosphorus‐based flame retardants synergistic flame retardant rigid polyurethane foam,” Polymer Engineering and Science 63(3), 1041-1049. DOI: 10.1002/pen.26264

Wu, M., Peng, J. J., Dong, Y. M., Pang, J. H., and Zhang, X. M. (2022). “Preparation of rigid polyurethane foam from lignopolyol obtained through mild oxypropylation,” RSC Advances 12(34), 21736-21741. DOI: 10.1039/D2RA02895F

Yang, W. P., Macosko, C. W., and Wellinghoff, S. T. (1986). “Thermal degradation of urethanes based on 4, 4′-diphenylmethane diisocyanate and 1, 4-butanediol (MDI/BDO),” Polymer 27(8), 1235-1240. DOI: 10.1016/0032-3861(86)90012-1

Zhang, H., Chen, H., She, Y., Zheng, X., and Pu, J. (2014). “Anti-yellowing property of polyurethane improved by the use of surface-modified nanocrystalline cellulose,” BioResources 9(1), 673-684. DOI: 10.15376/biores.9.1.673-684

Zhou, X., Sain, M. M., and Oksman, K. (2016). “Semi-rigid biopolyurethane foams based on palm-oil polyol and reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals,” Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 83, 56-62. DOI: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.06.008

Article submitted: December 11, 2023; Peer review completed: January 27, 2024; Revised version received and accepted: March 6, 2024; Published: March 20, 2024.

DOI: 10.15376/biores.19.2.2842-2862