Abstract

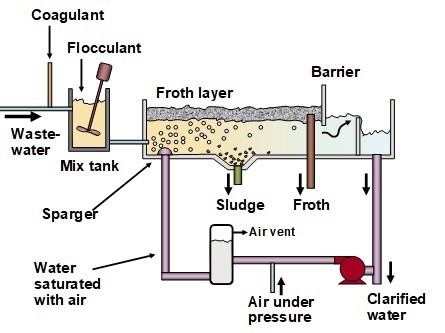

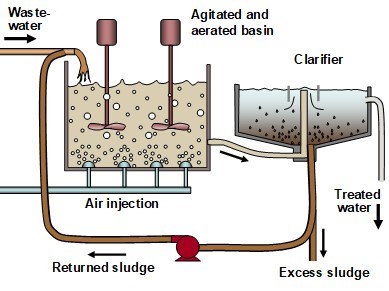

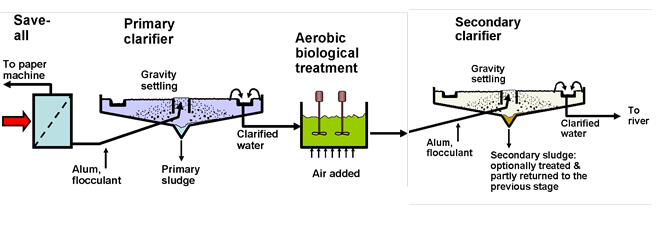

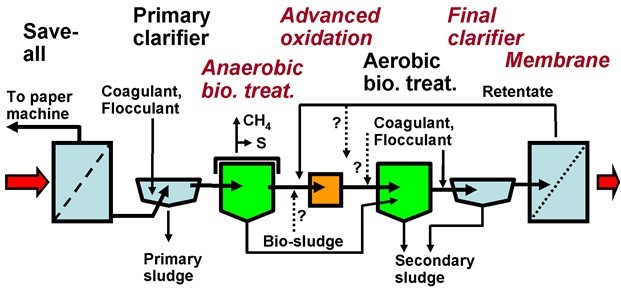

The pulp and paper (P&P) industry worldwide has achieved substantial progress in treating both process water and wastewater, thus limiting the discharge of pollutants to receiving waters. This review covers a variety of wastewater treatment methods, which provide P&P companies with cost-effective ways to limit the release of biological or chemical oxygen demand, toxicity, solids, color, and other indicators of pollutant load. Conventional wastewater treatment systems, often comprising primary clarification followed by activated sludge processes, have been widely implemented in the P&P industry. Higher levels of pollutant removal can be achieved by supplementary treatments, which can include anaerobic biological stages, advanced oxidation processes, bioreactors, and membrane filtration technologies. Improvements in the performance of wastewater treatment operations often can be achieved by effective measurement technologies and by strategic addition of agents including coagulants, flocculants, filter aids, and optimized fungal or bacterial cultures. In addition, P&P mills can implement upstream process changes, including dissolved-air-flotation (DAF) systems, filtration save-alls, and kidney-like operations to purify process waters, thus reducing the load of pollutants and the volume of effluent being discharged to end-of-pipe wastewater treatment plants.

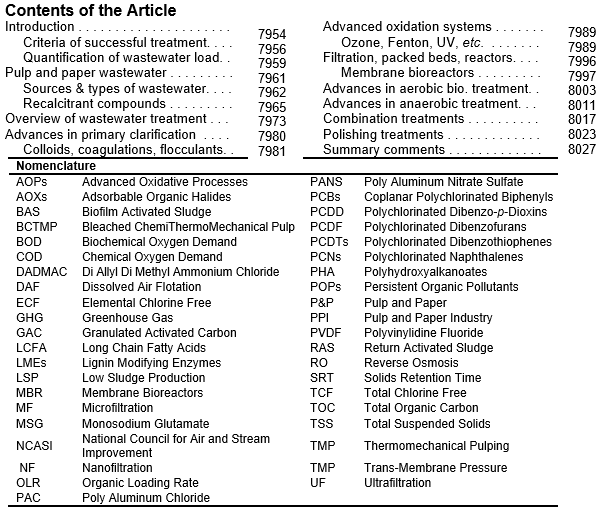

Download PDF

Full Article

Wastewater Treatment and Reclamation: A Review of Pulp and Paper Industry Practices and Opportunities

Martin A. Hubbe,*,a Jeremy R. Metts,a,b Daphne Hermosilla,c M. Angeles Blanco,d Laleh Yerushalmi,e Fariborz Haghighat,e Petra Lindholm-Lehto,f Zahra Khodaparast,g Mohammadreza Kamali,h and Allan Elliott i

The pulp and paper (P&P) industry worldwide has achieved substantial progress in treating both process water and wastewater, thus limiting the discharge of pollutants to receiving waters. This review covers a variety of wastewater treatment methods, which provide P&P companies with cost-effective ways to limit the release of biological or chemical oxygen demand, toxicity, solids, color, and other indicators of pollutant load. Conventional wastewater treatment systems, often comprising primary clarification followed by activated sludge processes, have been widely implemented in the P&P industry. Higher levels of pollutant removal can be achieved by supplementary treatments, which can include anaerobic biological stages, advanced oxidation processes, bioreactors, and membrane filtration technologies. Improvements in the performance of wastewater treatment operations often can be achieved by effective measurement technologies and by strategic addition of agents including coagulants, flocculants, filter aids, and optimized fungal or bacterial cultures. In addition, P&P mills can implement upstream process changes, including dissolved-air-flotation (DAF) systems, filtration save-alls, and kidney-like operations to purify process waters, thus reducing the load of pollutants and the volume of effluent being discharged to end-of-pipe wastewater treatment plants.

Keywords: Wastewater treatment; Pulp and paper manufacturing; Advanced oxidation; Membrane technologies; Clarification; Activated sludge

Contact information: a: North Carolina State University, Dept. of Forest Biomaterials, Campus Box 8005, Raleigh, NC 29695-8005; b: WestRock Company, Water and Waste Treatment, 600 S 8th St, Fernandina Beach, FL 32034; c: Department of Agricultural and Forestry Engineering, University of Valladolid, Campus Duques de Soria, E-42004 Soria, Spain; d: Complutense University of Madrid, Department of Chemical Engineering, Ingn. Quim, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Ciudad Universitaria s/n,S-N, E-28040 Madrid, Spain; e: Concordia University, Dept. Bldg. Civil & Environm. Engn., 1455 Maisonneuve Blvd, West Montreal, PQ H3G 1M8, Canada; f: University of Jyväskylä, Dept. Chem., Box 35, FI-40014 Jyväskylä, Finland; g: Department of Biology, Center for Environmental and Marine Studies, CESAM, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; h: Department of Environment and Planning, Center for Environmental and Marine Studies, CESAM, Aveiro & Department of Materials and Ceramics, Institute of Materials, CICECO, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; i: FPInnovations, 570 St. Jean Blvd., Pointe Claire, PQ H9R 3J9, Canada; * Corresponding author: hubbe@ncsu.edu

INTRODUCTION

The pulp and paper (P&P) industry occupies a challenging position with respect to the natural environment. On the positive side, the industry is based on the usage of renewable, photosynthetic resources. On the other hand, the industry discharges huge quantities of aqueous effluents. Large volumes (up to 70 m3) of wastewater are generated for each metric ton of paper produced, depending on the nature of raw material, the type of finished product, and the extent of water reuse (Rintala and Puhakka 1994; Latorre et al. 2007). The P&P industry uses about 70% of its massive water intake as process water. Reducing water consumption, by increasing internal water recirculation after the implementation of internal cleaning processes, saves money and also decreases the use of scarce environmental resources. The industry has reduced water consumption over the past 20 years by nearly a half and over the past 30 years by an impressive 95% per tonne of paper (Blanco et al. 2004). Since the main unit operations associated with pulping and papermaking are carried out in aqueous media, the application of various chemical additives can considerably alter the properties of the produced effluents, making it harmful for the receiving environments. The total closure of the water circuits is limited by the accumulation of contaminants in the process water, which can give rise to corrosion, deposits, and odors and alter the runnability of the paper machine and the quality of the final product. If further closure is required, then the effluent has to be extensively treated so that it can be used again in the process.

The main pollutants discharged to water streams nowadays are solids and organic matter. In general, pulp and paper mill effluents contain a complex mixture of various classes of organic compounds, such as degradation products of carbohydrates, lignin, and extractives (Uğurlu et al. 2008; Uğurlu and Karaoğlu 2009). Polluting effluents are formed in wood preparation, pulping, pulp washing, screening, paper machine, and coating operations, and especially in bleaching operations (Ali and Shreekrishnan 2001; Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004; Savant et al. 2006). Clearly, the properties of wastewater from various process stages depend on the type of process and raw material, the recirculation of the effluent, and the amount of water used (Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004). The effluents contain high values of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and chlorinated chemicals that are collectively termed as absorbable organic halides (AOX). While AOX content is generally proportional to the chlorine consumption in bleaching (Savant et al. 2006), this emission has been reduced by over 80% since 1990 (Friere et al. 2003). The ratio of BOD to COD is a particularly useful quantity because it represents the fraction of organic compounds in the effluent that are easy to degrade (McCubbin and Folke 1993). Chemical pulping processes have been reported to generate more than 40% of poorly biodegradable organics within the total organic matter of the effluent (Dahlman et al. 1995).

If the wastewater were to be discharged without treatment, then the adverse effects would include depletion of dissolved oxygen, toxic effects on fish and other aquatic organisms, and unacceptable changes to color, turbidity, temperature, and solids content of the receiving waters. Issues related to toxicity have been the focus of much attention (Walden and Howard 1981; Owens 1991; Kamali and Khodaparst 2015). For the protection of the environment, and also to satisfy legal requirements, it is necessary for the industry to remove harmful materials from wastewater before it is discharged to the environment. For example, in the US the establishment of “cluster rules” for regulation of discharges from P&P facilities (Vice et al. 1996; Swann 1998; Vice and Carroll 1998) provided major incentive for reductions in discharged pollutants. In China part of the solution to the same issues has been to replace older manufacturing facilities with new capacity that is better suited to the minimization of wastewater impacts (Zhang et al. 2012).

In Canada, the discharge of wastewaters from pulp and paper mills into water frequented by fish is controlled by the Pulp and Paper Effluent Regulations (PPER). These regulations aim at protecting water quality that sustains fish, fish habitat and the use of fisheries resources. The PPER set limits on the amounts of total suspended solids (TSS) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), and prohibit the discharge of effluents that display acute lethality to fish (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2016). Secondary treatment for the biological break down of biodegradable material and toxic components, resulting in reductions in biochemical oxygen demand, toxicity and total suspended solids, became common by 1996 following the establishment of current regulatory limits in 1992. Environmental regulation of pulp and paper mills also includes the Pulp and Paper Mill Effluent Chlorinated Dioxins and Furans Regulations, issued under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA), to control the level of dioxin and furan in the effluent of mills using a chlorine bleaching process. Additionally, Pulp and Paper Mill Defoamer and Wood Chip Regulations, also issued under the CEPA, govern the use of defoamers containing dibenzofuran or dibenzo-para-dioxin and wood chips from wood that was treated with polychlorinated phenols (Environmental Compliance Insider 2010).

In Europe, the Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control Directive sets permit conditions based on the use of best available technologies published in the BREF documents (BREF 2015), and voluntary agreements through the Confederation of European Paper Industries (CEPI) further enhanced the sustainability behavior.

Although the focus of this article is on the treatment of wastewater, it is important to keep in mind that purification of the effluent water is not the only goal. A wider goal is to achieve a sustainable P&P production in which environmental performance and competitiveness go hand in hand to supply a wide range of useful products. For efficient water use and treatment, a sustainable integrated water management is motivated by multiple drivers including: legislation; protection against water-related risks in water stress regions; limits in sensitive water bodies; cost of water; business opportunities; general expectation; proudness of the company; and corporate image, etc. Within this approach the concept of water-fit-for-use is becoming increasingly important; therefore attention will be paid in this review to which approaches tend to be cost-effective and sufficient to meet the different water quality demands.

Much of the content of the present article can be regarded as an overview of “best practices” in terms of wastewater and process water treatment technologies that have been implemented in the P&P industry. The article aims to provide explanations not only of practices that have become widely used in the industry, but also of practices that hold the potential of greater effectiveness of wastewater treatment in the future within the P&P industry. Ideally, wastewater treatment operations ought to be regarded as highly reliable, highly effective, cost-competitive, and evidence of good stewardship on the part of industry leaders.

The subject of treating the effluent and process water from P&P manufacturing facilities has been considered earlier, with emphasis in a number of key areas. The toxicity of such wastewater and its potential effects on the environment have been reviewed by Ali and Sreekrishnan (2001). Review articles by Pokhrel and Viraraghavan (2004), Zhao et al. (2014), and Kamali and Khodaparast (2015) provide background for different types of treatment facilities. Bajpai and Bajpai (1994) reviewed strategies for the removal of color from P&P mill wastewater. Various articles have focused on the performance and “best available technology” for treating P&P mill wastewater in different regions (Lescot and Jappinen 1994; Hammar and Rydholm 1972; Gehm 1973; Rajvaidya and Markandey 1998; European Commission 2001; Demel et al. 2003; Tiku et al. 2007; Menezes et al. 2010; Zhu et al. 2012; BREF 2015). Regarding advanced oxidation systems applicable as a primary or a tertiary treatment, the review by Bautista et al. (2008) gives excellent descriptions of Fenton (iron/ hydrogen peroxide) wastewater treatment systems, though P&P applications are not considered. Hermosilla et al. (2015) reviewed the implementation and development of advanced oxidation systems implemented for P&P mill effluents. Buyukkamaci and Koken (2010) focus on the economic aspects of different wastewater treatment options available for P&P mill effluent. Various authors have considered options of treating the process water so that it can be reused within the normal operations of papermaking (Tenno and Paulapuro 1999; Verenich et al. 2000; Webb 2002; Nuortila-Jokinen et al. 2004; Hubbe 2007c; Ordóñez et al. 2010; Mauchauffee et al. 2012; Saif et al. 2013). Wider review articles and books dealing with general aspects of wastewater treatment have appeared (Scott and Ollis 1995; Thompson et al. 2001; Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004; Singh et al. 2012; Riffat 2013; Ranade 2014; Spellman 2014; Zhao et al. 2014; Hopcroft 2015; Blanco et al. 2016; Fatta-Kassinos et al. 2016). Finally, Ince et al. (2011) reviewed strategies that can be implemented in the P&P industry to prevent pollution.

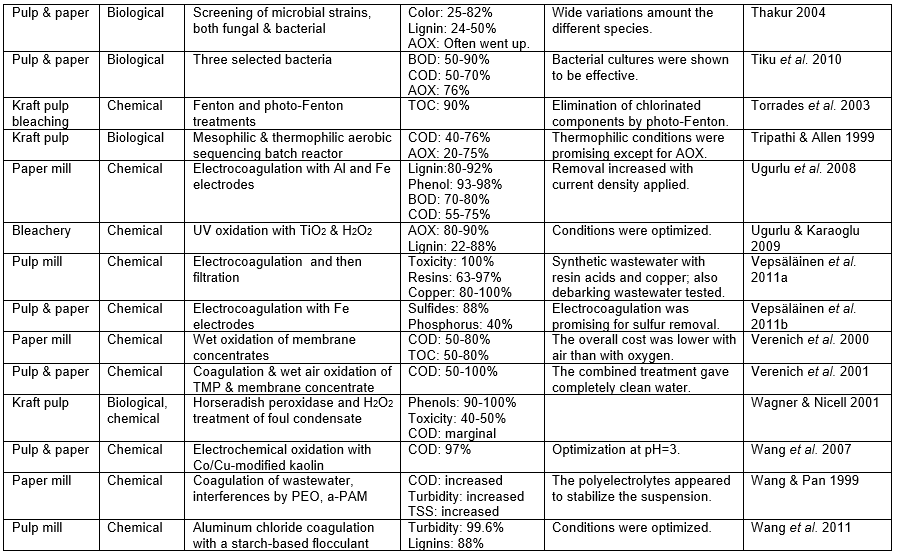

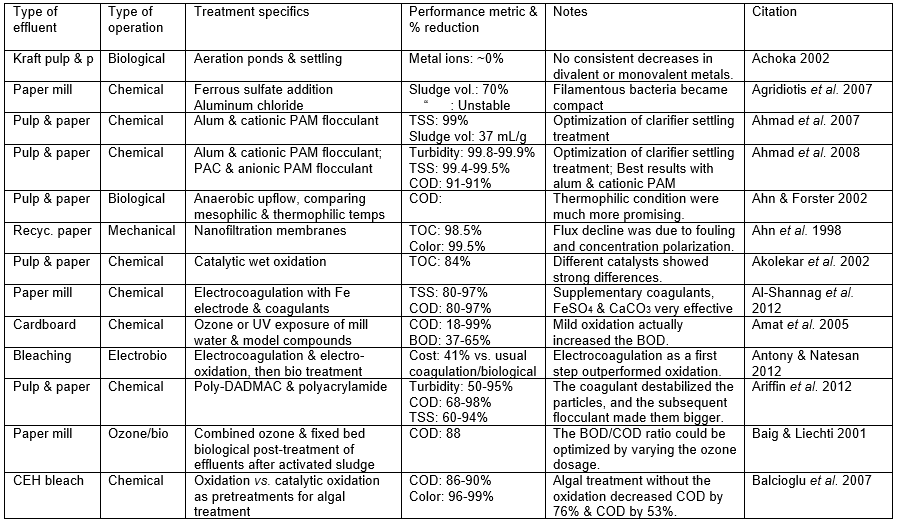

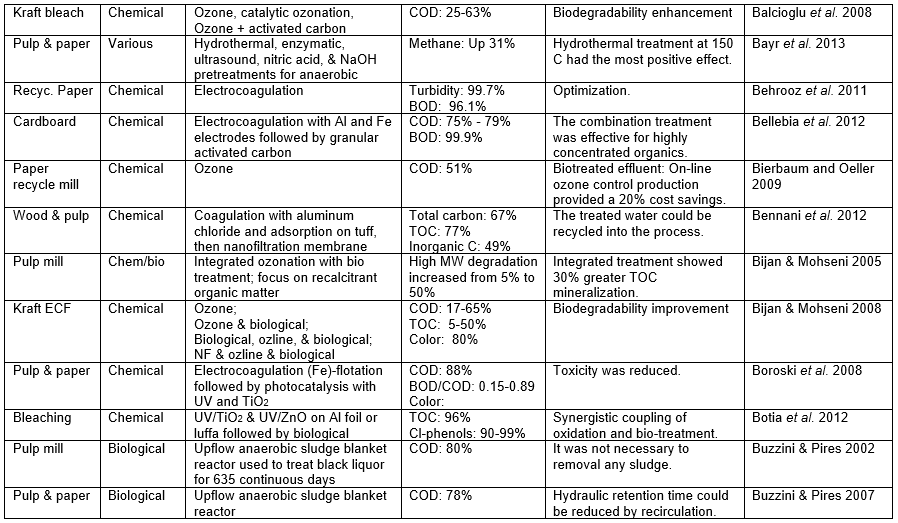

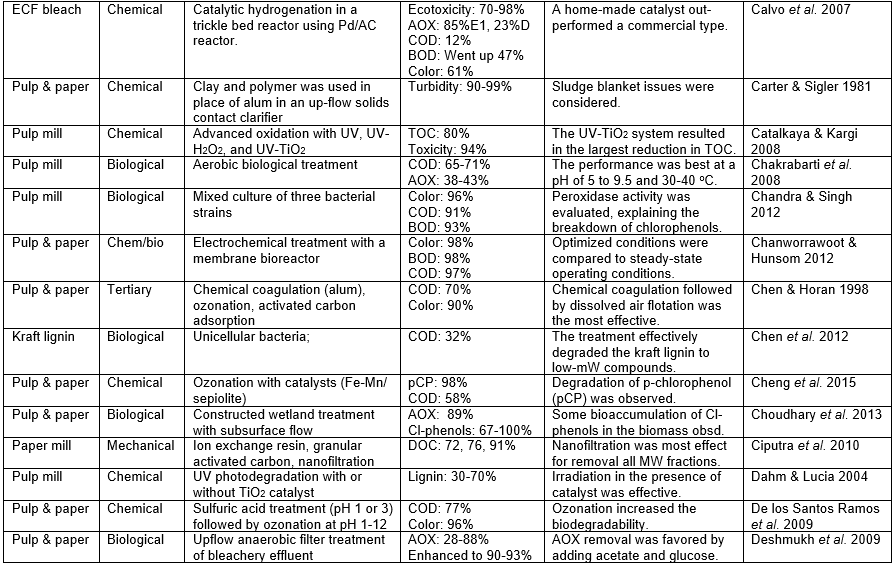

Criteria of Successful Treatment

Those who set out to remove pollutants from the wastewater of P&P manufacturing facilities face a variety of challenges, the difficulty of which will depend a lot on the nature of the wastewater that needs to be treated. The challenge also will depend on the required purity to be achieved in the treated water. To begin with, any successful wastewater management system needs to clearly define water demands and water qualities for different uses in order to optimize water reuse based on the principle of water-fit-for-use, where water is treated only to the required quality. Second, the final effluent must be treated to accomplish the discharge limits. Table A in the appendix of this article lists the percentage removal values reported in a wide range of studies devoted to the treatment of P&P wastewater. In addition, it is important to achieve stable and reliable operations of both the pulp/papermaking process and the wastewater treatment system.

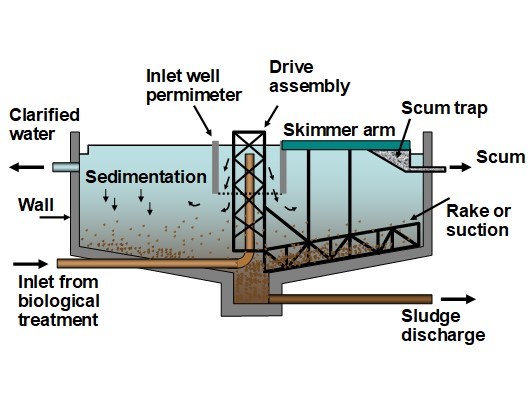

Settling or flotation rate, speed of processing

The rate of separation of wastewater solids in a waste treatment plant can limit the throughput of settling or flotation units. On the other hand, if methods can be developed and optimized to accelerate separation, then the size and capital costs of the plant might be reduced. Various researchers have shown that separation rates can be sped up by chemical treatments (Leitz 1993; Al-Jasser 2009). Furthermore, the use of some hybrid chemicals can promote the removal of a higher percentage of organic matter or specific inorganic material (e.g. silica) with the solids (Miranda et al. 2015). The operating conditions of the biological treatment plant can affect settling rates (Avella et al. 2011). Elliott and Mahmood (2012) found that biological sludge digestion could be optimized to speed up the process of handling the sludge.

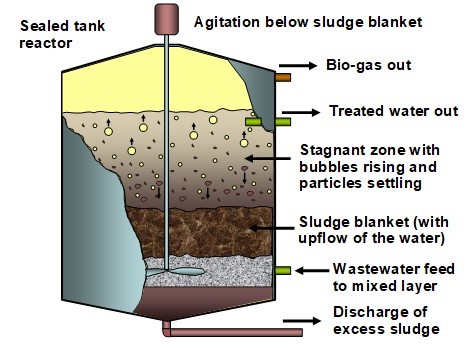

Quantity of sludge

In recent years there has been increasing realization that, in addition to removing pollutants from the wastewater, it is important to minimize the amount of solid waste sludge that is generated as a byproduct of the treatment operations (Leitz 1993; Tripathi and Allen 1999; Alvares et al. 2001; Mahmood and Elliott 2006; Chanworrawoot and Hunsom 2012). One way to reduce sludge is to place increased emphasis on anaerobic biological treatment as an early step in the treatment program (Ashrafi et al. 2015; Kamali and Khodaparast 2015; Ordóñez et al. 2010). Alternatively, researchers have shown that thermophilic (higher temperature) biological treatment systems can achieve better efficiency and lower sludge amounts even under aerated conditions (LaPara and Alleman 1999; Skouteris et al. 2012). Also, by carrying out the treatment in stages, much of the initial sludge volume can be consumed by other types of organisms living within different zones within wastewater treatment operations (Lee and Welander 1996). Optimum sludge dewatering is also important, as well as the maximum removal of dissolved and colloidal material to keep the water circuit relatively clean. In conjunction with the development of technologies to minimize sludge production, avenues have been explored to utilize the generated sludge for beneficial purposes as opposed to just bearing expenses for treatment and removal of waste (Elliott and Mahmood 2005).

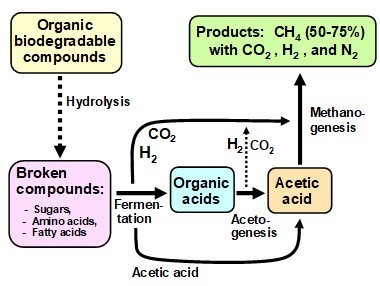

Greenhouse gas emissions

While the main goal of wastewater treatment is to remove pollutants from wastewater, one of the secondary goals, as we look to the future, is to minimize the production of other pollutants, such as gaseous emissions. Ashrafi et al. (2015) emphasized impacts of different wastewater-treatment options on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In addition to the evolution of CO2, methane, and other GHG components from the waste materials, one also needs to be concerned about GHGs associated with the usage of electrical energy during the treatment of wastewater (Baig and Liechti 2001; Ashrafi et al. 2015). For instance, though improved efficiencies and treatment rates often can be achieved with modern reactors designed for biological wastewater treatment, such operations sometimes may require more electrical energy in comparison to conventional treatment systems (Castillo and Vivas 1996; Buzzini and Pires 2002; El-Ashtoukhy et al. 2009). According to Kamali and Khodaparast (2015), a goal of saving electrical energy costs may be responsible for a more widespread use of mesophilic (medium temperature) rather than thermophilic (higher temperature) conditions in biological treatment plants, even though the latter have been reported to achieve higher performance in many cases. In fact, some of the generated effluents already have a relatively high temperature, so they can already be handled in the thermophilic range without further chilling the effluent. Anaerobic wastewater treatment operations are often regarded favorably by environmental advocates because they actively generate methane that can be retrieved and used in place of other combustible fuels (Maat and Habets 1987; Tabatabaei et al. 2010; Saha et al. 2011; Meyer and Edwards 2014; Sanusi and Menzes 2014).

GHG emissions by on-site and off-site processes in a typical industrial wastewater treatment plant that used aerobic, anaerobic, and hybrid anaerobic/aerobic treatment processes were studied by Bani Shahabadi et al. (2009, 2010) and Yerushalmi et al. (2011). Yerushalmi et al. (2013) and Ashrafi et al. (2013, 2014, 2015) estimated GHG emission and energy consumption by wastewater treatment plants of the P&P industry and determined the contribution of individual processes to the on-site and off-site GHG emissions. On-site GHG emissions are due to liquid and solid treatment processes as well as biogas and fossil fuel combustion for energy generation. Off-site GHG emissions are related to the production of electricity for plant, production, and transportation of fuel and chemicals for on-site use, degradation of remaining constituents in the effluent of wastewater treatment plant, as well as transportation and disposal of solids. The on-site biological treatment processes were shown to make the highest contribution to GHG emissions in the aerobic treatment system, while the higher usage of chemicals in anaerobic and hybrid treatment systems resulted in higher GHG emission from material production and transportation in those treatment systems. The recovery of biogas, generated during anaerobic treatment processes or anaerobic sludge digestion, and its reuse as fuel were shown to have a remarkable impact on GHG emissions and reduction of the overall emissions. Biogas recovery and reuse as fuel can cover the total energy needs of the treatment plants for aeration, heating, and electricity, considerably reducing the net GHG emissions in the treatment plants. Heating of an anaerobic digester was identified as a major energy-demanding process, suggesting that solid digestion at lower temperatures should be exercised to reduce the associated GHG emissions.

Based on the results of studies published by the above investigators, the manufacturing of material for on-site consumption should use methods that generate lower amounts of GHGs, thus reducing upstream GHG emissions attributed to the wastewater treatment plant. Electricity and fossil fuels should also be generated and handled by more efficient methods in order to decrease the overall GHG emissions of treatment plants.

Another strategy for GHG emissions reduction is to use alternative nutrient removal processes such as the anaerobic Anammox process (Greenfield and Batstone 2005), which removes nitrogen with a lower consumption of energy and lower carbon use. In this process, the reduced aeration energy consumption reduces GHG production related to energy demands of the treatment plant, while the extra available carbon can be converted to methane via anaerobic processes and be used as a source of energy for on-site consumption, further reducing GHG emissions. The use of hybrid anaerobic/aerobic systems for wastewater treatment under optimized operating conditions was shown to be the most appropriate option for pulp-and-paper industry to obtain a satisfactory treatment performance, reduce GHG emission and energy costs, and meet environmental regulations.

Operating costs justified

Closely related to the topic of energy usage is the topic of operating costs. Hammar and Rydholm (1972), when reviewing the state of the art of wastewater treatment in the 1970s, complained about the relatively high cost of treatments capable of removing biodegradable organic pollutants. Although aerated biological treatment has long been regarded as a highly reliable and predominant approach utilized within the P&P industry, the pumping of the air represents one of the major operating costs of such systems (Maat and Habets 1987). Advanced oxidation systems, which have the potential to remove some of the most challenging toxic or highly colored components from P&P mill effluents, also have been criticized for their high operating costs (Heinzle et al. 1992; Byukkamaci and Koken 2010). Membrane treatments are also very efficient, and they are becoming more popular due to substantial reductions in membrane prices.

Quantification of Wastewater Load

Before considering different approaches used for the minimization or removal of contaminants from wastewater, the subsections below address some of the most common criteria for assessing the quality of treated water (McKeown and Gellman 1976; Owens 1991). Standard methods for the most widely used tests have been established in the US by the American Public Health Association (APHA 2001, 2005). In Europe, the corresponding standards are in the EU Directive 91/271/EEC of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Oxygen demand

From an environmental standpoint, biodegradable substances, which are quantified in terms of the biological oxygen demand (BOD) test, are generally regarded with favor. However, if such materials were to be discharged into rivers, lakes, and estuaries at excessive levels, the resulting biological metabolism would sometimes be sufficient to consume all or most of the available dissolved oxygen, leading to the death of fish and other aquatic life (Taylor et al. 1996; Chhonkar et al. 2000). Such impacts are often quantified by measuring the BOD. This quantity is evaluated by sealing a volume of water to be tested with a known amount of gaseous oxygen; the level of oxygen gas in the container is measured five days later (BOD5 test), after microbes have had a chance to reproduce and to consume the decomposable organic materials (APHA 2016, Standard Method 5210). As can become evident from inspection of the contents of Table A (see Appendix), the BOD test is among the most frequently used methods to characterize untreated and treated wastewaters.

It has been recently shown that microbial consortia that have become acclimated to the degradation of lignin-related compounds can reduce the BOD levels in the pulp-and-paper wastewaters below levels that are normally achievable by using indigenous microorganisms (Ordaz-Diaz et al. 2014). BOD levels also have been found to correlate with the pulping yield and with the color in the treated wastewater from P&P mill facilities (Bajpai and Bajpai 1994).

The oxidizable matter in a wastewater also can be measured by the chemical oxygen demand (COD) test (APHA 2001). The COD test takes advantage of the relatively rapid reaction of potassium dichromate with the oxidizable materials in the water sample. The results from BOD and COD tests will be different if the wastewater sample contains difficult-to-biodegrade oxidizable compounds or toxic materials that inhibit biological activities. Thus the ratio of BOD to COD is often reported as a way to quantify the relative recalcitrance of organic compounds in wastewater (Yeber et al. 1999b; Baig and Liechti 2001; Kreetachat et al. 2007; Ghaly et al. 2011). This value, which is often in a range between about 0.05 and 0.5 for P&P wastewaters, will help to determine what treatment strategy is appropriate.

Color

The color of an organic chemical compound, i.e. its ability to absorb visible light, generally requires a sufficiently long sequence of single and double carbon-carbon bonds, i.e. a conjugated structure (Adachi and Nagao 2001). The lignin component of wood is highly susceptible to becoming strongly colored due to its high content of aromatic rings, in addition to other unsaturated structures (Sarkanen 1971). Thus, although natural lignin present in native wood generally has a light color, deep coloration develops during kraft pulping. Indeed, the appearance of “black liquor,” the spent alkaline solution left over after kraft pulping, can be attributed to such compounds. As noted by Bajpai and Bajpai (1994), highly colored compounds in typical pulping and bleaching wastewaters often are resistant to biodegradation and removal during treatment operations. The sources and types of colored compounds that develop during pulping and papermaking have been reviewed (NCASI 2011). Measures to remove color from the effluent of P&P mills have been reviewed and reported (Bajpai and Bajpai 1994; Garg and Tripathi 2011; Garg et al. 2012). Langergraber et al. (2004) discussed the evaluation of color in such wastewater by instrumental methods.

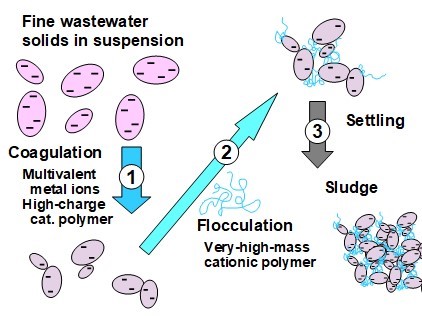

Total suspended solids (TSS) and turbidity

Suspended matter in wastewater has the potential to obstruct the passage of light and interfere with the respiration of aquatic organisms. These contaminants are commonly quantified as the total suspended solids (TSS) and turbidity. The TSS values are determined by weighing the solid matter filtered from a water sample onto a tared piece of standard filter paper composed of glass fibers (APHA 2016, Standard Method 2540). Some of the most effective measures for reducing TSS are separation of solids by sedimentation, flotation, or membrane techniques. Treatment of the raw wastewater with coagulants and flocculants, at optimized dosages, can promote the speed and completeness of such separations.

Toxicity

Toxic compounds may be present in wastewaters of pulping facilities, but they are not common in papermaking processes. They are a matter of concern (Lugowski 1991; Owens 1991; Ali and Sreekrishnan 2001) not only because of their toxic effects on the environment (Mahmood-Khan et al. 2013), but also they may disrupt the beneficial biological activities during wastewater treatment operations (Freire et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2011). Discharged effluents having toxic content can damage the reproductivity of aquatic species (Costigan et al. 2012; Waye et al. 2014). According to Magnus et al. (2000) long-chain fatty acids, generated during pulping operations, constitute one of the primary sources of toxicity coming from pulping operations. Chlorinated organic compounds, and dioxin in particular, have been noted for their toxic and often carcinogenic effects (Safe 1990; Wiegand et al. 2006). The presence of toxic substances (mainly AOX and dioxins) in effluents from pulp bleaching has been reduced by 95% down to a level of ≤0.1 KgAOX·t-1 of pulp since 1990, mainly thanks to the replacement of chlorine gas by elemental-chlorine-free and total-chlorine-free chemicals in bleaching processes (Aspapel 2011; CEPI 2013). Kostamo and Kukkonen (2003) reported that secondary wastewater treatment with activated sludge can be effective for the removal of toxicity.

Recalcitrant, persistent compounds

Organic compounds that resist biodegradation are of great concern because they can remain in the wastewater even after it has been treated by widely used aerobic biological processes that employ activated sludge (Gergov 1988; Scott and Ollis 1995; Magnus et al. 2000; Contreras Lopez 2003) or with anaerobic biological wastewater treatment (Korczak et al. 1991; Sierraalvarez et al. 1991). Eriksson and Kolar (1985) employed isotopic labeling to explore the mechanisms involved in the biodegradation of such compounds. Efforts to eliminate such compounds by alternative treatment methods such as advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have been widely reported (Rodriguez et al. 1999; Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004; Eskelinen et al. 2010; Merayo et al. 2013; Lindholm-Lehto et al. 2015). AOPs can be employed either as pretreatment to increase the biodegradability of the organic solids or as post-treatment to remove the remaining organic content. Inoculation of wastewater treatment systems with lignin-degrading fungal species has shown promise in breaking down the recalcitrant compounds and reducing the toxicity levels (Pellinen and Joyce 1990; Thakur 2004), in spite of the inherent issues arising from such methods such as low tolerance of the fungal strains for variations in pH.

Sulfur content

Sulfur-containing compounds in aqueous wastewaters are considered a problem because of possible action of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the environment. Anaerobic conditions can lead to the generation of toxic H2S gas, as well as other sulfur-containing compounds that contribute to unpleasant odors (Smet et al. 1998; Devai and DeLaune 1999; Goyer and Lavoie 2001). The removal of sulfur from pulp-and-paper wastewaters will be discussed in a later section (Lens et al. 1998; Janssen et al. 2009).

Salt, electrical conductivity

Inorganic salts and ionic compounds such as sodium chloride in industrial wastewaters can significantly increase the salinity and electrical conductivity of the receiving waters (Gehm 1973; Achoka 2002). Upset conditions in a P&P mill, causing the release of alkaline pulping liquors, can be detected by conductivity measurements (Kemeny and Banerjee 1997). Sulfates may also be limited by regulation or contract when treated effluents are discharged.

PULP AND PAPER WASTEWATER

The closure degree of P&P mill water circuits depends on the type of product. While water circuits can be highly closed for brown grades (Pietschker 1996; Gubelt et al. 2000), a total closure without the application of advanced treatment processes is not practical for chemical pulping processes and for manufacturing of white paper grades. Because the nature of different waste streams from P&P operations has been reviewed in other publications (Gehm 1973; Costa et al. 1979; Ashafi et al. 2015; Kamali and Khodaparast 2015; Blanco et al. 2016), such subjects will be treated only briefly here.

Sources and Characteristics of P&P Wastewater

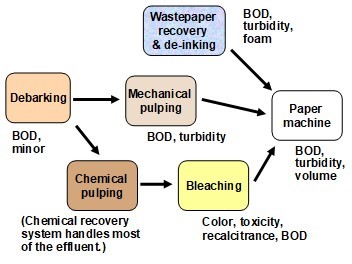

The first point worth emphasizing is that wastewater characteristics are highly variable, especially when comparing one pulp or papermaking operation to another. Much of the observed variation can be attributed to the different characteristics of wastewater streams emerging from specific kinds of pulping, bleaching, or papermaking processes (Gehm 1973; Hubbe 2007b; Hossain and Ismail 2015; Kamali and Khodaparast 2015). Also, the nature of the effluent will be dependent on how much fresh water is being utilized in the process. Figure 1 provides a snapshot of the categories or “streams” of wastewater mentioned in subsequent paragraphs.

Fig. 1. Main categories of contaminated water within a typical pulp and paper manufacturing facility, with an indication of important potential environmental impacts

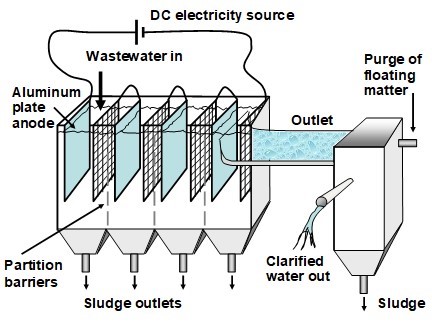

Debarking

Following the sequence of the manufacturing process, one of the first streams of contaminated water is associated with soaking of logs and removal of bark (Gehm 1973; Vepsäläinen et al. 2011). Because mainly mechanical processes are involved in bark removal, the levels of contamination resulting from debarking tend to be relatively low in comparison to other wastewater streams. For example, Vepsäläinen et al. (2011) showed that such wastewater could be effectively treated by electro-coagulation. Furthermore, dry debarking allows reducing wastewater production and potentially making it possible to obtain more energy from the bark in a power boiler (BREF 2015).

Mechanical pulping

The type of virgin pulp most often used in the production of newsprint and high-circulation magazine papers is obtained by mechanically separating the fibers in wood. Though this is another mainly mechanical process, the amount of energy expended per unit mass of generated pulp is high, and that may explain why there is significant release of soluble and particulate materials into the water phase (Stephenson and Duff 1996). Mechanical pulping is often carried out at elevated temperatures, i.e. thermomechanical pulping (TMP), which enables softening of the lignin between the fibers, making it possible to preserve a much greater proportion of full-length fibers during the separation process. The heating is probably responsible for increased release of material into the water phase (Rintala and Puhakka 1994; Stephenson and Duff 1996; Kortekaas et al. 1998; Willfor et al. 2003), though the literature search did not reveal data to support such an expectation. The peroxide-bleaching of thermomechanical pulp (BCTMP) is known to convert hemicellulose components of TMP into negatively charged carboxylate species, which readily enter into solution and can contribute to the pollutant load (Sundberg et al. 2000; Puro et al. 2010; Hubbe et al. 2012b; Miao et al. 2013). In general, however, high-yield pulps contribute relatively low levels of COD to the effluent.

Kraft pulping

Because kraft pulping and optional subsequent bleaching of wood-based and non-wood cellulosic pulps can involve solubilization of about 30 to 60% of the solid mass, depending on the manufacturer’s objectives (Biermann 1996), it is easy to understand why such operations have the potential to produce highly contaminated wastewaters. The leftover liquid after a kraft cooking process (the black liquor) is rich in lignin byproducts, as well as alkali, sodium sulfate, and the soaps of resin acids and fatty acids, among other contaminants (Vishtal and Kraslawski 2011; Lehto and Alén 2015).

Under ideal circumstances a very high percentage of the solubilized matter from alkaline pulping is circulated back to the chemical recovery system, diverting the potential contaminants away from the wastewater treatment system (Biermann 1996). But when the fiber source contains a high content of silica, as is the case for many annual plant types of biomass, the chemical recovery can be very difficult due to the deposition of inorganic scale on the equipment (Deniz et al. 2004). In addition, conventional bleaching technologies, based on chlorine dioxide, sodium hypochlorite, and related chemicals, yield wastewaters that would be excessively corrosive to the equipment used for chemical recovery, hence discouraging the recovery of pulping chemicals from such wastewater streams. The condensate collected during evaporative concentration of spent pulping liquor is a notable source of toxicity and odor, which needs to be treated (Wagner and Nicell 2001; Tielbaard et al. 2002).

Pollutants from various stages of bleaching of kraft pulps are among the most difficult to remove from wastewater (Prat et al. 1988; Kemeny and Banerjee 1997; Vidal et al. 1997; Yeber et al. 1999b; Kansal et al. 2008; Uğurlu and Karaoğlu 2009; Quezada et al. 2014; Larsson et al. 2015). Many of these compounds may have some adverse effects on the receiving media, such as formation of slime and scum, toxic effects to the exposed living organisms, and thermal impacts (Ali and Sreekrishnan 2001; Catalkaya and Kargi 2008; Garg and Tripathi 2011) or they are highly colored (Bajpai and Bajpai 1994).

Sulfite pulping process

The production of sulfite pulp is presently much smaller than the production of kraft pulp because of generally worse strength properties. However, sulfite pulp does provide better properties in terms of some specialty pulp applications. Different sulfite processes, such as acid (bi)sulfite, magnefite, or neutral sulfite, may mainly be applied by just changing the pH and the type of base that is used in the process. The sulfite cooking process uses aqueous sulfur dioxide (SO2) and a base of magnesium, calcium, sodium or ammonium. Chemical and energy recovery, as well as water use, will be affected by the selected base type. Magnesium sulfite pulping is the dominating process in Europe (≈11 mills), and there is another mill using sodium base, because both types allow chemical recovery. Lignosulfonates, sugars, and other substances that are generated within the cooking liquor might further be used as raw materials for the production of different chemical products. As noted by Rintala and Puhakka (1994), it is a high priority to remove toxicity from the evaporator condensate in a sulfite plant’s recovery cycle. Most of these sulfite pulp mills operate biological treatment plants to purify wastewater generated in different processes (washing losses, effluents from the bleach plant, and condensate from the evaporation plant, mainly) (BREF 2015).

Paper recycling operations

When fibers are recovered from recycled papers, a wider spectrum of contaminants will be present due to the variability in the nature of the used paper materials, their contamination during paper’s use and recovery, and the additives that are used for dispersing the fibers, removing ink, and bleaching (Muhamad et al. 2012a). Such waters are characterized by a high organic dissolved load, which typically has an anionic character (Miranda et al. 2009a).

In the past, deinking wastes were regarded as posing challenges during their clarification (Gehm 1973). Difficulties in gravitational separation of solids from deinking operations might be attributable to the dispersants that are widely used to separate the ink particles from the fibers. In this case, adequate coagulants and flocculants are required to destabilize the colloidal material and promote the aggregation of particles for their removal by sedimentation or dissolved air flotation (DAF). The past challenges during the clarification of de-inking waters generally have been solved, and these days it is possible to treat and reuse the effluents by membrane procedures, although silicic ions have to be removed to increase the recovery in reverse osmosis (RO) units (Ordóñez et al. 2011). Though the focus here is on the water-borne pollutants, it is important to bear in mind that a deinking process can result in the generation of large amounts of solid wastes; it has been estimated that about 70% of solid wastes, mainly in the form of sludge, are generated by de-inking operations (Monte et al. 2009).

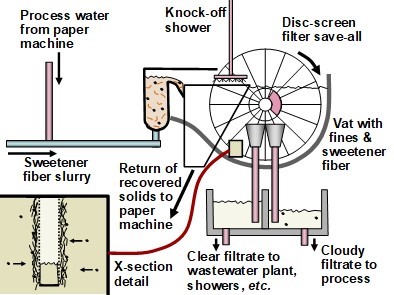

Papermaking operations

The paper machine itself, in some respects, can be regarded as having the cleanest process water circuit in the plant. Excess water from the forming and press sections of the paper machine is clarified by filtration (i.e. a save-all operation) or by DAF and reused in the papermaking process. When high quality water is required, for example in high-pressure showers, a further treatment such as ultrafiltration (UF) can be used.

On the other hand, the process water in a paper machine system, i.e. the “white water”, can contain a variety of additives, including mineral filler products such as calcium carbonate, clays, and titanium dioxide. Sizing agents, such as rosin products, alkenylsuccinic anhydride, or alkylketene dimer, are typically added to the fiber slurry in the form of emulsions, and not all of this is retained in the paper product. In the case of colored papers, though they are usually present at low amounts, dyes are important in terms of wastewater treatment on account of their high visibility.

Substantial pollutant loads can be expected whenever certain additives to the paper machine wet end are poorly retained in the product (Bilitewski et al. 2012). Starch products, which are rendered soluble in water by cooking operations, are commonly added to paper furnish at levels as high as 1% of the product mass (Howard and Jowsey 1989; Formento et al. 1994). Most of that wet-end-added starch is of the cationic form, and its positive charge favors a relatively high efficiency of retention onto the negatively charged fibers (Roberts et al. 1987; Howard and Jowsey 1989). By contrast, the surface-applied starch (“size-press starch”) is typically uncharged “pearl” starch, which does not have any electrostatic attraction to the fiber surfaces. The size press starch can be routinely added at amounts several times larger than what is practical at the wet end of the paper machine. Thus, when defective paper, i.e. “dry-end broke”, is repulped and sent back to the paper machine, a high proportion of the surface-applied starch may end up in the aqueous phase, such that it later can be discharged to the wastewater treatment plant.

Recalcitrant Organic Compounds in Pulp and Paper Mill Wastewaters

Pulp and paper mill effluents contain a variety of recalcitrant materials, such as lignosulfonic acids, chlorinated resin acids, chlorinated phenols, dioxins, and chlorinated hydrocarbons (Kumara Swamy et al. 2012; Singh and Srivastava 2014). Although in most cases the toxicity is low, effluents from pulp bleaching are characterized by high strength of COD (1000 to 7000 mg L-1), low biodegradability ratio (BOD5/ COD) ranging from 0.02 to 0.07, and a moderate strength of suspended solids (500 to 2000 mg L-1) (Ramos et al. 2009; Eskelinen et al. 2012). Compounds, especially those containing chlorine (measured by the parameter AOX) are recalcitrant because they contain chemical structures uncommon in nature, such as the carbon-chlorine bond (Jokela et al. 1993; Mounteer et al. 2007a). It is widely reported that high molecular weight (HMW > 1 kDa) organic matter in bleaching effluents is more recalcitrant to biological treatment than low molecular weight (LMW < 1 kDa) organic matter (Dahlman et al. 1995; Savant et al. 2006). Dissolved lignin and its degradation products, hemicelluloses, resin acids, fatty acids, diterpene alcohols, juvaniones, tannins, and phenols (Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004) are responsible for the dark color and toxicity of the effluent (Malaviya and Rathore 2007; Chopra and Singh 2012).

Lignin and its derivatives

Among the main biomass components, lignin is the most difficult to degrade by biological means (Kumar et al. 2010; Pu et al. 2015). It is a three-dimensional amorphous polyphenolic polymer that is primarily biosynthesized from three typical types of phenylpropanoid precursors: coniferyl, sinapyl, and p-coumaryl alcohol (Thakur 2004). Once incorporated into the lignin polymer, these monomers form guaiacyl, syringyl, and p-hydroxyphenyl lignin subunits. The lignin macromolecule is primarily linked via ether bonds and carbon-carbon bonds among phenylpropanoid units (Samuel et al. 2014).

Lignin is degraded during pulp and paper production to a variety of high, medium, and low molecular weight chlorinated and non-chlorinated fractions (McKague 1981). In particular, the HMW lignin compounds are not effectively degraded during conventional effluent treatment, and the majority of such compounds in wastewater may be discharged into receiving waters (Hyötyläinen and Knuutinen 1993). Lignin and its derivatives are recalcitrant and highly toxic compounds responsible for the high BOD and COD values of effluents as well as the dark brown color of pulp effluents formed during pulping (Wong et al. 2006). In pulp bleaching, chlorine reacts with lignin, its derivatives, and other organic matter present in the pulp, forming highly toxic and recalcitrant compounds, such as chlorinated lignosulfonic acids, chlorinated resin acids, chlorinated phenols, guaiacols, catechols, benzaldehydes, vanillins, syringo-vanillins, and chloropropioguaiacols (Knuutinen 1982; Kringstad and Lindström 1984; Thakur 2004). Especially in acidic media, lignin molecules tend to undergo self-condensation, and they subsequently show resistance to degradation (Ali and Sreekrishnan 2001). Chlorolignins mostly end up in the effluent of the alkaline extraction stage, which is a major source of AOX, COD, BOD, and color (Sun et al. 1989; Ali and Shreekrishnan 2001).

Chlorinated organic compounds

In pulp and paper mill effluents, hundreds of chlorinated organic compounds have been identified, including chlorinated hydrocarbons, phenols, catechols, guaiacols, furans, dioxins, syringyl lignin, and vanillins (Suntio et al. 1988; Freire et al. 2003). Organochlorine compounds are usually biologically persistent, recalcitrant, and highly toxic to the environment (Baig and Liechti 2001; Thompson et al. 2001). They have been detected especially in water and sediments in the vicinity of pulp and paper mill effluents (Virkki et al. 1994; Munawar et al. 2000; Lacorte et al. 2003). Organochlorine compounds are widespread and are found even in relatively pristine environments (Abrahamsson and Klick 1991). The recalcitrance of an individual compound towards biological processes is related to the number and position of the halogen substituents (Naumann 1999). Additionally, enantioselectivity and chiral discrimination of optically active compounds can have an influence on the degree of their accumulation (Reich et al. 1999; Vetter and Maruya 2000). Isomers, diastereomers, and enantiomers can have varying toxicity (Willett et al. 1998; Carr et al. 1999).

Chlorinated phenols are synthetic compounds, typically formed by hydrolysis of chlorobenzenes and in pulp bleaching (Kringstad and Lindström 1984). Chlorophenols may also be formed as by-products in paper production, cooking processes, or distillation of wood (Paasivirta et al. 1983, 1988; Öberg et al. 1989). Monomeric chlorophenols include 19 compounds of mono-, di-, tri-, and tetrachloroisomers and pentachlorophenol. Generally, they are crystalline solids at room temperature, excluding the liquid orthochlorophenol (Ahlborg 1977).

In the bleaching operations following kraft wood pulping, HMW and LMW chlorinated organic compounds are formed, the latter comprising of about 250 smaller chlorinated compounds (Rantio 1997). In pulp bleaching, chlorophenolics are present both in free (hexane extractable) and bound (extractable with strong alkali) forms and bound to dissolved organic matter and particles (Paasivirta et al. 1992). For example, chlorophenols, guaiacols, and catechols are formed in high quantities (Suntio et al. 1988; Koistinen et al. 1990), guaiacols and catechols being chemically bound to chlorolignin (Schechter et al. 1990). They can be methylated by microorganisms to more persistent and lipophilic forms as chloroanisoles, veratroles, or aromatic chloroethers, which are persistent derivatives of chlorophenolics. In addition, during the cooking and chlorine bleaching, chlorinated cymenes, (methyl-(methylethyl)benzenes, CYMS) and cymenenes (methyl-(methylethenyl)-benzenes, CYMD) are formed (Kuokkanen 1989; Rantio 1997). Chlorinated cymenes were first identified in the effluents of kraft pulp and sulfite mills in the late 70s, and dechlorinated cymene compounds have been found both from kraft and sulfite mills and chlorinated compounds from kraft pulp mills (Bjørseth et al. 1977). Residues of CYMS and CYMD have been found in fish and mussels in the recipient water bodies (Paasivirta et al. 1984; Herve 1991), and they can be employed as indicators of the exposure of biota to effluents from pulp bleaching (Rantio 1997).

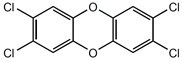

Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDD) and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDF) are two classes of tricyclic, aromatic, and lipophilic compounds that contain some of the most toxic chemical substances ever known (Kringstad and Lindström 1984). PCDD and PCDF are formed as side products in chlorophenol production and in thermic reactions, such as combustions and chlorinations but also in pulp and paper production (Alcock and Jones 1996; Kim et al. 2002). In pulp production, the PCDD and PCDF are mostly formed by condensation of polychlorinated phenoxyphenols in pulping and by chlorination of dibenzofuran and dibenzo-p-dioxin in pulp bleaching (Hrutfiord and Negri 1992; Luthe and Berry 1996; Yunker et al. 2002).

Generally, a mixture of different PCDD and PCDF is formed, but isomers with chlorine atoms in the 2, 3, 7, and 8 positions (7 PCDD and 10 PCDF) are the most toxic to organisms, with 2,3,7,8 tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, as shown in Fig. 2, being the most toxic (Malisch 2000; Fueno et al. 2002). PCDD and PCDF are acute or chronic toxins, recalcitrant and persistent in nature due to their lipophilic properties and resistance to biological and chemical degradation (Vallejo et al. 2015). This leads to biomagnification along food chains and various degrees of toxic effects (Van den Berg et al. 2006). They have been classified as priority pollutants by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA 1998) and ‘dirty dozen’ group of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) identified by United Nations Environment Program (UNEP 1995). Dioxins are named as ‘known human carcinogens’ by the World Health Organization (WHO 1997).

Fig. 2. Chemical structure of 2,3,7,8 tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

PCDD and PCDF have been detected, e.g. in bleach plant effluents, bleached paper products, sediments of the receiving waters, and fish living in the recipient water bodies (Rappe et al. 1989; Clement et al. 1989; Lacorte et al. 2003). The elimination of dibenzofuran and dibenzo-p-dioxin from defoamer products, the exclusion of chlorophenol-contaminated wood chips, and the introduction of chlorine dioxide bleaching have dramatically decreased the production of PCDD and PCDF in the P&P effluents (Hagen et al. 1997; Yunker et al. 2002).

Other chlorinated and non-chlorinated substances that are released from pulp mills include planar aromatic compounds, which can be characterized as alkylated polychlorodibenzofurans, alkyl polychlorobiphenyls, and alkyl polychlorophenanthrenes (Paasivirta 1988; Wiberg et al. 1989). Their levels are orders of magnitude higher than those of dioxins and furans in pulp mill effluents, several nanograms per gram in dry weight (Paasivirta 1991). Polychlorinated dibenzothiophenes (PCDTs) are sulfur analogues of polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs) and have structural resemblance to PCDDs and PCDFs (Sinkkonen 1997; Koivisto 2001). In addition, other compounds may have dioxin-like toxicity, including the non-chlorinated ones, such as indocarbazoles, benzanthracenes, and benzoflavones (Paasivirta 1988).

During the last decades, there has been a drastic decrease in the use of molecular chlorine as a bleaching agent, and it has been replaced with chlorine dioxide (Elementary Chlorine Free, ECF), molecular oxygen, peroxide, or ozone (Totally Chlorine Free, TCF), which has led to a drastic decrease in AOX, PCDD, and PCDF (Shimp and Owens 1993; Rantio 1997). There are several modifications made to reduce the generation of chlorinated organic compounds from bleach plant effluents by employing modified strategies. A key strategy involves removing more lignin i.e., by extended delignification, reducing the kappa number of unbleached pulp. Further strategies involve modifying the conventional bleaching process to ECF and TCF bleaching (Kinstrey 1993). This reduction of chlorine content in the effluents has made it possible to improve the closure of the water circuits system of the mill and to recycle the bleach plant effluent back to the mill’s chemical recovery system. The reduction of the generation of organic substances in bleaching stages has been possible thanks to previously increasing delignification efficiency, modifying cooking, additional oxygen stages, spill collection systems, a more efficient washing, and stripping and reusing condensates. The installation of external treatment plants of different designs has been another successful contributing factor to decreasing AOX and unchlorinated toxic organic compounds emissions to receiving water (BREF 2015). In Canada as a result of federal regulations, the quality of pulp and paper effluent released directly to the environment has progressively improved. In 2013, 96.2%, 99.9%, and 99.8% of effluent samples met regulatory requirements for toxicity tests on fish, BOD, and TSS, respectively (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2016).

Non-chlorinated recalcitrant compounds

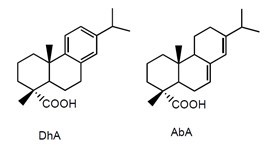

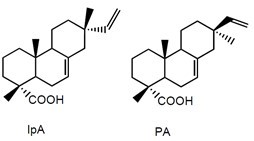

Wood extractives are hydrophobic components that are soluble in neutral solvents. They are composed of e.g. resin acids, fatty acids, sterols, diterpene alcohols, and tannins (Holmbom 1999; Lacorte et al. 2003). Resin acids, as shown in Fig. 3, are tricyclic diterpenoids and natural constituents of conifer wood. Fatty acids exist as free fatty acids and neutral esterified fatty acids in triglycerides and steryl esters (Ekman and Holmbom 2000; Björklund Jansson and Nilvebrant 2009). Generally, fatty acids include palmitic, linolenic, linoleic, and oleic acids, while resin acids include abietic, neoabietic, levopimaric, palustic, and dehydroabietic acids (Back and Ekman 2000). Resin acids are released in high amounts during pulping and paper production, especially in mechanical pulp production (Johnsen et al. 1993). Resin acids are very resistant to chemical degradation due to their stable tricyclic structure (Dethlefs and Stan 1996). They are thought to be the main contributors to the toxicity of the pulp mill effluents (Makris and Banerjee 2002; Rigol et al. 2004) and have been reported to end up in sediments of the receiving water bodies (Dethlefs and Stan 1996; Rämänen et al. 2010).

Fig. 3. Chemical structures of typical resin acids that may be released from softwood species during pulping (DhA = dehydroabietic acid; AbA = abietic acid; IpA = isopimaric acid; PA = pimaric acid)

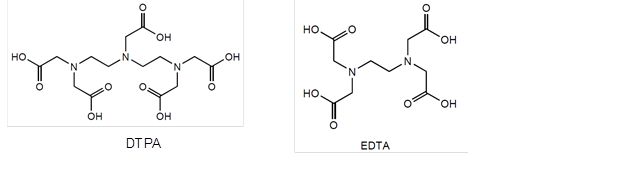

In addition to substances originating in the wood, there may be situations in which P&P wastewater contains toxins from other sources. Many of the organic substances produced by the chemical industry are toxic or resistant to biological treatment (Lapertot et al. 2006; Muñoz and Guieysee 2006). Chelating agents, such as DTPA and EDTA (Fig. 4), are relatively large organic molecules that are able to bind metals (Tana and Lehtinen 1996). They are increasingly used with peroxide and ozone bleaching of wood pulp and discharged with spent bleach liquors. Chelating agents have been reported to either totally resist degradation or to undergo slow biodegradation (Hinck et al. 1997). They have been found e.g. in marine sediment, but so far no direct harmful effects in the environment have been reported (Sprague et al. 1991; Puustinen and Uotila 1994). However, it has been suggested that chelating agents can prevent the sedimentation of metals close to the point of discharge, leading to the spread of metals over a large area in low concentrations (Tana and Lehtinen 1996).

Fig. 4. Molecular structures of two widely-used chelating agents (DTPA = diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid; EDTA = ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid)

Toxicity of Recalcitrant Compounds

The discharged pollutants of the pulp and paper mill effluents affect both aquatic and terrestrial organisms (Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004). Several studies have reported toxic effects on fish species due to pulp mill effluents, including respiratory stress, liver damage, mutagenic, and genotoxic effects (Owens et al. 1994; Johnsen et al. 1998; Leppänen and Oikari 1999; Schnell et al. 2000b; Rana et al. 2004). Sublethal effects and changes in plankton population have been reported (Yen et al. 1996; Baruah 1997), but also delayed sexual maturity, changes in reproduction, smaller gonads, and altered productivity of aquatic invertebrates and fish (Munkittrick et al. 1997; Karels et al. 1999). Additionally, decreased number of juveniles, physiological and skin diseases, and changes in communities, population structure, and in growth rates of fish have been observed (Sepúlveda et al. 2002). Furthermore, effluents from pulp bleaching impair the quality of fish and fish flesh in the receiving waters (Herve 1991; Redenbach 1997).

Increase in the amount of toxic substances in water kills zooplankton and fish, affecting the terrestrial ecosystem (Burton et al. 1983). Other problems may occur due to failure of the treatment processes employed to treat the pulp and paper mill effluent. This can result in the release of suspended solids and nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, which can lead to eutrophication of the receiving water bodies and oxygen depletion (Thompson et al. 2001). Endocrine disruptors may be also present in the wastewater (Balabanic et al. 2012), though relatively little is known about potential endocrine disruption effects of paper mill effluents on aquatic organisms. For example, plant sterols (phytosterols) may act as disrupters of the hormonal and biochemical systems of aquatic organisms (Kostamo and Kukkonen 2003). Pulp mill effluents are known to contain varying amounts of phytosterols, which have the structure similar to that of the steroid hormones of vertebrates (Lehtinen et al. 1999). In addition, transformation products of sterols can have androgenic (Stahlschmidt-Allner et al. 1997) and hermaphroditic effects on fish near sewage treatment plants (Zachrazewski et al. 1995; Lacorte et al. 2003).

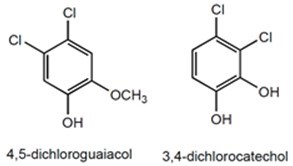

Chlorinated compounds

Chlorinated phenolics and chlorinated lignin derivatives are a group of chemicals contributing greatly to the toxicity of pulp and paper mill effluents (Walden and Howard 1981). Multiple adverse health effects have been linked to organochlorine compounds, such as endocrine disruption (growth retardation, thyroid dysfunction, decreased fertility and feminization or masculinization of biota) and impaired liver function in fish exposed to these effluents (Oikari and Nakari 1982; Munkittrick et al. 1998; Lacorte et al. 2003). Chlorinated phenols, catechols, and guaiacols are known to cause mutagenesis in mammalian cells (Hattula and Knuutinen 1985). Two examples of such molecules are shown in Fig. 5. Additionally, lignin and its derivatives are toxic to aquatic organisms and animals (Priha and Talka 1986).

Fig. 5. Molecular structures of two chlorinated phenols

Even though chlorinated phenolics represent less than 2% of the organically bound chlorine in bleaching effluents, they are large contributors to effluent toxicity, carcinogenicity, and mutagenicity (Savant et al. 2006; Kukkola et al. 2011). The majority of organochlorinated compounds present in pulp and paper mill effluents are HMW chlorolignins (>1 kDa). These compounds are likely to be biologically inactive and have a small contribution to the toxicity, mutagenicity, and BOD of pulp mill effluents (Hileman 1993; Ali and Shreekrishnan 2001). On the other hand, LMW compounds (<1 kDa) are the main contributors to mutagenicity and bioaccumulation because they can penetrate cell membranes (Heimberger et al. 1988; Sun et al. 1989). They can bioaccumulate in the aquatic food chain in the body fat of animals in higher trophic levels (Renberg et al. 1980; Ali and Shreekrishnan 2001). However, there are indications that also derivatives of HMW lignin exhibit toxicity (Pessala et al. 2010).

Acute toxicity of chlorinated phenolics increases with the degree of chlorination, the more distant position of chlorine atom relative to the phenolic hydroxyl group, and with chlorophenol lipophilicity (Loehr and Krishnamoorthy 1988; Sierra‑Alvarez et al. 1994). Chlorinated phenolics with the chlorine at position 2 are less toxic than the other chlorophenols, while toxicity increases as a chlorine atom is substituted at 3, 4, and 5 positions (Saito et al. 1991; Czaplicka 2004). The bioaccumulation potential increases with the number of chlorine substituents on the phenolic ring. Phenol and most of the chlorophenolic compounds can induce mutations in certain bacteria and yeasts (Smith and Novak 1987). Chlorophenols are less readily biodegradable than phenol, and their rate of biodegradation decreases with increasing number of chlorine substituents on the aromatic ring (Banerjee et al. 1984). It has been suggested that position of the substituent has an effect on the degradability; the order for chlorophenols was found to be ortho > meta > para during anaerobic conditions in aquifer sediments and in digested sludge (Boyd and Shelton 1984; Genthner et al. 1989; Annachhatre and Gheewala 1996).

Dioxins are found to bioaccumulate in fish downstream of pulp and paper mills, while chlorophenolic compounds, coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) isomers, polychlorinated naphthalenes (PCNs), polychloroanthracenes, tetrachloroazo- and azoxybenzenes, and PCDEs are acutely toxic but not very prone to bioaccumulation (Paasivirta 1988; Howie et al. 1990; Frakes et al. 1993). However, chlorinated hydrocarbons (e.g. hexachlorocyclohexanes, residues of DDT (dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane), chlordanes, PCNs, and PCBs) have shown high bioaccumulation rates and biomagnification at higher trophic levels (Paasivirta 1988; Herve et al. 1988; Paasivirta and Rantio 1991; Koistinen 1992).

Extractives

Wood extractives, e.g. resin and fatty acids, sterols, and diterpene alcohols account for a large part of toxicity in various paper mill effluent streams (Lacorte et al. 2003). In particular, the toxicity of resin acids has been studied extensively for decades (e.g. Oikari et al. 1984; Meriläinen et al. 2007). The most commonly monitored resin acids in aqueous pulping effluents include abietic acid, dehydroabietic acid, neoabietic acid, pimaric acid, isopimaric acid, sandaracopimaric acid, levopimaric acid, and palustric acid, among which isopimaric acid is the most toxic (Wilson et al. 1996). Additionally, retene (7-isopropyl-1-methylphenanthrene) is a naturally formed polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon causing teratogenicity in fish larvae. Retene is formed in surface sediments contaminated by resin acids from pulp mill effluents (Oikari et al. 2002).

The toxicity of tannins to several enzymes has been well established (Korczak et al. 1991; Sierra-Alvarez et al. 1994). Methanogenic toxicity of tannins depends on the degree of polymerization (Field et al. 1988). HMW tannin polymers and humic acids exhibit low toxicity because their size limits their ability to penetrate into the bacterial cells. The highest toxicity is found in oligomeric tannins due to their ability to form strong hydrogen bonds with proteins (Field et al. 1989; Sierra-Alvarez et al. 1994). Condensed tannins from spruce bark are toxic, not only to methanogens at concentrations present in the paper mill wastewaters, but also to aquatic organisms, such as fish (Field et al. 1988; Temmink et al. 1989). In addition, unsaturated fatty acids (16-C and 18-C) of softwood, such as oleic acids, linoleic acid, and linolenic acid are also a source of toxicity to fish, especially salmonoids (Voss and Rapsomatiotis 1985). Long chain fatty acids (LCFA) have been shown to inhibit methanogenic bacteria (Koster and Cramer 1987). This makes the anaerobic treatment of wastewaters relatively troublesome since methanogenic bacteria play a crucial role in the anaerobic wastewater treatment.

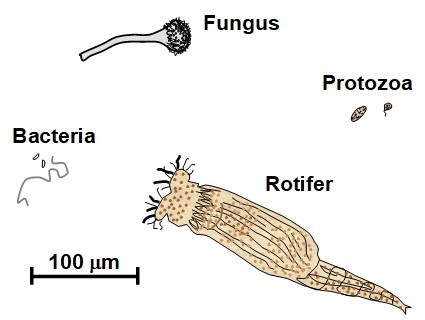

Biological Processes – Susceptibility to Enzymatic Breakdown

Microorganisms with lignolytic properties can degrade contaminants in pulp and paper mill effluents containing toxic and recalcitrant compounds (Thakur 2004). Lignolytic microorganisms include fungi, actinomycetes, yeast, bacteria, and algae, all of which can produce enzymes responsible for lignocellulose degradation (Bajpai and Bajpai 1994; Annachatre and Gheewala 1996). Enzymatic treatment can be applied as a single step or with other physical and chemical methods, as extensively reviewed by Chen et al. (2010), Saritha et al. (2012), and Barakat et al. (2014).

Fungal enzymes, collectively termed as ligninases or lignin-modifying enzymes (LMEs), can degrade lignin into simple sugars and starch (Bocchini et al. 2005; Dashtban et al. 2010; Chopra and Singh 2012). Ligninases can be classified as phenol oxidases (laccase) or heme peroxidases (Martínez et al. 2005). The latter is further subdivided as lignin peroxidases, manganese peroxidases, and versatile peroxidases (Singh and Shrivastava 2014). Depending on the species of fungi, one or more of the lignin-modifying enzymes can be secreted. For example, white-rot fungi (e.g. P. chrysosporium) are able to degrade lignin efficiently using a combination of extracellular ligninolytic enzymes, organic acids, mediators, and accessory enzymes (Singh and Shrivastava 2014). Even though lignin peroxidase is able to oxidize the non-phenolic part of lignin (which forms 80 to 90% of the lignin composition), it is absent from many lignin-degrading fungi (Wang et al. 2008a). Enzymes able to perform dechlorination are generally termed as dehalogenases (Savant et al. 2006). These enzymes are able to degrade a variety of environmentally persistent pollutants, such as chlorinated aromatic compounds, heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, and various dyes (Singh and Shrivastava 2014).

A broad range of fungi degrade lignin to varying degree (Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004). They include soil fungi (Fusarium sp.), soft rot fungi (Populaspora, Chaetomium sp.), pseudo soft rot fungi (Hyoxylen, Xylaria), lignin degrading fungi (Callybia, Mycena), white rot fungi (Trametes, Phanerochaete), and brown rot fungi (Gleophyllium, Poria). They can also degrade modified lignin and their derivatives found in effluent but also COD, AOX, and color from pulp mill effluents (Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004). White-rot fungi, particularly P. chrysosporium and C. versicolor, can degrade refractory material efficiently and reduce color, lignin, and COD (Bajpai and Bajpai 1994). However, only a few strains of fungi can reduce chlorinated aromatic compounds (Bajpai and Bajpai 1997; Singh 2007). White-rot basidiomycetes, such as Coriolus versicolor (Wang et al. 2008a), P. chrysosporium, and T. versicolor (Moreno et al. 2003) have been found to be the most efficient lignin-degrading microorganisms.

In nature, lignin is degraded during wood decay mainly by basidiomycetes white-rot fungi, of which many attack lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose simultaneously, e.g. Trametes versicolor (Tanaka et al. 1999) or Heterobasidium annosum (Daniel et al. 1998), whereas some other white-rot fungi preferentially work on lignin in a selective manner, e.g. Physisporinus rivulosus (Hilden et al. 2007) and Dichomitus squalens (Fackler et al. 2006).

Enzymatic treatment is a safe and ecofriendly process (Kim et al. 2002), but a long residence time is required (up to 10‑14 days), and high costs of enzymes limit its commercial applications (Pu et al. 2015). Furthermore, selectivity of enzymes can be low and also carbohydrates are partially consumed by microorganisms. So far, enzymatic treatment of pulp and paper mill effluent generally has not been successful due to a lack of suitable organisms, various recalcitrant compounds, and poor process optimization for industrial-scale treatment.

Recalcitrant compounds and their treatment

Approximately half of the organic matter in typical pulp and paper mill effluent is recalcitrant to biodegradation by both anaerobic and aerobic bacteria (Ortega-Clemente et al. 2009). For example, wood resin, tannins, and chlorinated phenolics are toxic to methanogenic bacteria (Rintala and Puhakka 1994; Vidal et al. 2001). However, certain bacterial strains are quite effective in breaking down recalcitrant organic phenolic compounds and their derivatives and can also reduce the color of pulp mill effluent to some extent (Bajpai and Bajpai 1997). Anaerobic bacteria able to degrade chlorinated organics are classified as alkyl dehalogenators and aryl dehalogenators (Mohn and Tiedje 1992). The alkyl dehalogenators include physiologically diverse groups of strict anaerobes and facultative anaerobes, such as methanogens, species of Clostridium, Acetobacterium woodii, and Shewanella (Savant et al. 2006). These organisms mainly dechlorinate LMW compounds, such as chloroform, tetrachloroethene, dichloromethane, trichloroethane, and trichloroethene. Aryl dehalogenators mainly belong to proteobacteria and genera, such as Desulfitobacterium and Desulfobacter.

Anaerobic bacteria are believed to use chlorinated organic compounds as a source of carbon and energy, as a cometabolite, or as an electron acceptor depending on the strain of bacteria (Holliger et al. 1998). Thus they are better suited to reductively dehalogenate highly chlorinated phenolics, while aerobic biological systems are suitable for less halogenated phenolics (Neilson 1990; Latorre et al. 2007). A sequence of anaerobic treatment followed by aerobic treatment permits the degradation of compounds that are non-degradable anaerobically (Rintala and Puhakka 1994).

Mixed microbial communities can overcome the problems faced by monocultures in the environment, such as nutritional limitations and toxic substrates (Thakur 1995; Kim et al. 2002). For example, a mixture of various bacteria can degrade phenolic compounds due to their varying structures and toxicity. In addition, two or more microorganisms can be applied sequentially, one carrying out the initial catabolic reactions and another completing the rest of the metabolic pathway to mineralize the organic compounds. Bicyclic aromatics such as chlorinated biphenyls, chlorinated dibenzofurans, and naphthalene sulfonates have been treated sequentially, resulting a reduction in color, lignin, COD, and phenol (Pokhrel and Viraraghavan 2004; Singh and Thakur 2006).

Susceptibility to oxidation

In the natural environment, many organic refractory compounds can be degraded, either biologically or by photochemical reactions, and further transformed by evaporation or adsorption (Czaplicka 2004). Photochemical processes include photodissociation, photosubstitution, photooxidation, and photoreduction. In the aquatic environment, photodegradation occurs only in the surface layer and is faster in summer than in winter, especially in the northern latitudes (Kawaguchi 1992a). The properties of chlorophenols are favorable to sorption and accumulation, especially into bottom sediment and suspended matter (Brusseau and Rao 1991; Peuravuori et al. 2002; Czaplicka 2004). Chlorophenols can undergo reactions of auto-oxidation and catalysis, especially on surfaces made of clay and silica. They can evaporate, with the rate depending on vapour pressure and water solubility, but under typical environmental conditions evaporation plays an insignificant role (Piwoni et al. 1989; Czaplicka 2004).

OVERVIEW OF WASTEWATER TREATMENT OPTIONS

Before reviewing advances in wastewater treatment technologies related to the P&P industry, an overview is presented of conventional approaches. These approaches address not only the treatment of such effluent, but also reducing its amount by implementing strategic changes to the operations within P&P mills. Wastewater treatment systems have commonly been understood to function as “end-of-pipe” solutions to environmental issues, whereas the least expensive way to treat polluted water may be to produce less of it in the first place (Stratton et al. 2004; Hossain and Ismail 2015). Unit operations within P&P mill water treatment systems have been reported before and can be mentioned here (European Commission 2001; Demel et al. 2003). Blanco et al. (2016) have recently reviewed the state of the art on water reuse.

Pulp Mill Operations and Wastewater

A process known as counter-current washing has been widely used within the P&P industry to effectively separate used cooking liquors from the cellulose fibers while minimizing the volume of rinse water (Hammar and Rydholm 1972; Ala-Kaila et al. 2005). Such systems are set up with a series of washing operations, such that the cleanest water is used to wash the cleanest pulp. The rinse water is directed backwards through the series of washers until the most contaminated rinse water enters the chemical recovery system.

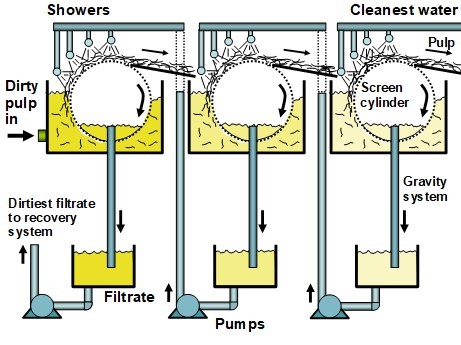

In modern pulp and paper making facilities it is still common to employ screen cylinders (i.e. “deckers”) which rotate slowly while partially submerged in a vat filled with pulp suspension (Fig. 6). A mat of pulp collects on the outer surface of the cylinder, as filtrate is removed by gravity from the space within the cylinder. Wash water is applied above the wet mat of fibers to displace the contaminated water with cleaner water. Lindau et al. (2007) demonstrated that higher efficiency can be achieved in such systems by improving the uniformity of the pulp pad. The counter-current principle can easily be applied to such systems by employing the filtrate from the final stage of washing as the rinse water for the next preceding stage, and so-on for the whole series of deckers. Such systems have been considered theoretically (Potucek 2003, 2005). Counter-current washing is also used in recovered paper mills. In such mills, water is used for cleaning operations and separated from the pulp through disk filters and pressed in such a way as to segregate filtrate streams having different levels of contamination. The separated waters then can be recirculated in different process loops, such as showers. The most contaminated water is circulated back to the pulper.

Fig. 6. Schematic of a series of three decker-type pulp washers, with counter-current washing

Continuous washing equipment has been installed in many modern pulp mills, especially those that employ continuous kraft digesting equipment, as a means to achieve more favorable washing efficiency and to minimize the amount of concentrated liquor that needs to be evaporated during the chemical recovery process (Richter 1966; Edwards and Rydin 1976; Lee 1979, 1984; Gullichsen 1999). In addition to incorporating the principle of counter-current washing, some additional gains in displacement efficiency have been achieved in such installations by avoiding the dense compaction of pulp within the pulp washing tower. Because the rinse water flows quite slowly from where it is injected towards a cylindrical screen in the tower, there is sufficient time for contaminants to diffuse from the fibers and become almost equilibrated with the rinse water at each point. Thus, higher overall efficiency can be achieved in comparison to systems that rapidly displace the contaminated water from a wet mat of pulp (Richter 1966; Potucek 2005; Lindau et al. 2007). By operating under pressure, some such designs make it possible to utilize very hot rinse water, while at the same time avoiding the generation of foam bubbles (Gullichsen 1999).

Oxygen delignification

Oxygen bleaching (often called extended delignification) does not involve corrosive chloride ions. Therefore, the wash water can be combined with the brown-stock wash liquor and directed back towards the chemical recovery system. This process reduces the emission of organic substances to the wastewater and the amount of chemicals to be added, which makes such an operation suitable for systems with high levels of water reuse (BREF 2015). In addition, research suggests that effluent from oxygen bleaching stages is highly biodegradable (Vidal et al. 1997). Furthermore, this stage will reduce the load of bleaching plant pollutants entering the biological wastewater treatment system. Hence, such a process can reduce the loading of organic material that otherwise would be released from the pulp during bleaching of a kraft pulp (Hammar and Rydholm 1972; Stratton et al. 2004). Oxygen delignification tends to be less selective than some other options, such as using chlorine dioxide. As a consequence, extensive oxygen delignification tends to break down the cellulose macromolecules, lowering the average molecular mass, and eventually weakening the material. Therefore, magnesium salts (typically MgSO4) are usually added, with the aim of preserving the strength of pulp.

Paper Mill Operations and Wastewater

Paper machine systems use large volumes of water. Nevertheless, there are many opportunities either to limit the amounts of substances dissolved in the water or to reuse the process water multiple times in the mill.

Separation of loops

A good strategy for sustainable water use is the separation of process water in several loops (1 to 4) to keep the water around the paper machine as clean as possible. Stock from a more contaminated process loop is transferred to the following one at high consistency to minimize the transfer of contaminant. Kappen and Wildered (2002) have developed a method to determine the efficiency of this approach based on the COD content at different stages of the process.

Increased retention of fines and polymeric materials