Abstract

The article deals with data in the cutting process of wood-based materials. The cutting process influences the shape and dimensions of a cutting edge. The experiments were focused on monitoring the changes of the cutting edge in machining of particle board and the influence of cutting speed on the tool wear. Cutting tests were performed during milling at cutting rates in the range 7.95 to 17.9 m/s (477 to 1074 m/min), a depth of cut of 9.5 mm, and a tooth feed of 0.05 mm. The wear process of cutting wedge during particle board milling is characterized by a decrease in the cutting edge of insert blades. The comparative digital dial gauge was used for measurement of the cutting wedge recession. The course of the wear of wood based materials exhibited similarity in graphical representation with abrasive material cutting. The resulting dependency may be used for selection of the most suitable cutting conditions according to operator requirements.

Download PDF

Full Article

Cutting Conditions and Tool Wear when Machining Wood-Based Materials

Josef Chladil,a* Josef Sedlák,a Eva Rybářová Šebelová,b Marián Kučera,c and Miroslav Dado c

The article deals with data in the cutting process of wood-based materials. The cutting process influences the shape and dimensions of a cutting edge. The experiments were focused on monitoring the changes of the cutting edge in machining of particle board and the influence of cutting speed on the tool wear. Cutting tests were performed during milling at cutting rates in the range 7.95 to 17.9 m/s (477 to 1074 m/min), a depth of cut of 9.5 mm, and a tooth feed of 0.05 mm. The wear process of cutting wedge during particle board milling is characterized by a decrease in the cutting edge of insert blades. The comparative digital dial gauge was used for measurement of the cutting wedge recession. The course of the wear of wood based materials exhibited similarity in graphical representation with abrasive material cutting. The resulting dependency may be used for selection of the most suitable cutting conditions according to operator requirements.

Keywords: Machining; Wood; Tool; Wear; Dulling; Cutting conditions

Contact information: a: Institute of Manufacturing Engineering, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, Brno University of Technology, Technická 2, 61600 Brno, Czech Republic, b: The Display Company CZ s.r.o., Londýnské náměstí 4, 63900 Brno, Czech Republic, c: Department of Manufacturing Technology and Quality Management, Faculty of Environmental and Manufacturing Technology, Technical University in Zvolen; * Corresponding author: jo.chla@seznam.cz

INTRODUCTON

Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic material, a natural composite of cellulose fibers, which are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin that resists compression. Wood is the one of few materials that are renewable (Kučerová et al. 2016). Unfortunately, wood is a relatively low-durability material and requires special care to assure a long-term service life. For that reason, modified or surface-coated wood-based materials are also widely used. To a certain extent, such wood-based materials preserve the good properties of wood and mitigate against some of its unfavorable properties (Kvietkova et al. 2015a,b,c; Gaff et al. 2016; Sedlecký and Sarvašová Kvietková 2017).

Mechanical and physical properties are important factors in wood processing. Agglomerated materials are made from wood or other lignocellulosic particles.

Particle board is a term for material made of wood particles that are produced in variety of shapes and sizes. Wood chips are bonded using synthetic glue, high pressure, and increased temperature. For interior use, these materials often need to be veneered, laminated, or folded to improve their appearance. The material is most widely used and most manufactured agglomerated material in the woodworking industry (Thoemen et al. 2010).

During the milling process, cutting inserts within the rotating tool separate the workpiece material in the form of chips. The feed rate is limited by size and type of cutting tool perpendicular to the machined part. The cutting process is intermittent, and the cutter teeth alternately cut short chips of varying thickness. Wood-based materials are milled in all directions, but most often along the direction of wood fibres. The direction of rotation is usually chosen to be conventional, i.e. against the feed rate direction. With respect to the position of the axis of rotation and the surfaces created by the cutting edges, the milling is divided into two types: either the cylindrical-tool axis is parallel with the workpiece surface, or the front-axis of the tool is perpendicular to the workpiece surface.

The milling process is monitored using the tool life. Tool life is the period during which the blade is in working condition in the machining process. It is the time when the tool is working, from sharpening to dulling. When machining the metal, abrasion wear process is observed on the clearance face of cutting edge and is referred to as VB flank wear. Figure 1 shows this process on the wear curve. The individual phases are: I – initial rapid wear, II – linear wear, and III – final unstable course. The practical wear measurement uses the value of critical wear VB in the linear phase II; this selection is due to the accuracy of the reading value (Shaw 2005; Csanády and Magoss 2012).

Fig. 1. Graphical representation of the dependence VB or KR = fn (T) in metal cutting

The cutting edge is formed by the intersection of two surfaces – the face plane (rake angle γ) and the clearance plane (clearance angle α). Darmawan et al. (2001, 2012) studied wear process on the clearance face influenced by different wood based materials and materials of cutting tool edge. During machining wood based materials without abrasives the wear on the tool edge recession is monitored depending on time (Šebelová and Chladil 2013). This type of wear is called nose wear (Shaw 2005; Mazan et al. 2017), and its size corresponds to radial wear KR (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The nose wear type of tool wear

In this study, a wood-based material – laminated particle board – was used to experimentally examine the influence of cutting conditions on tool wear. Cylindrical milling was used to test properties of the tool material in the cutting process, and a two-tooth right-hand milling cutter was applied. The tool dulling process was monitored because this affects cutting tool lifetime and thus also the machining efficiency. The Taylor’s time vs. cutting speed formula was used for evaluation (Shaw 2005).

EXPERIMENTAL

Workpiece Material

Laminated particle board was used as the representative of wood-based materials laminated with beech. The supplier of the laminated particle board (045 BS beech Westfalen 18mm thick) was INTEREXPO Brno Ltd, Czech Republic. The board volume weight was 600 to 750 kg.m-3 and moisture 14.2% determined according to EN 323 (1993).

Cutting Tool

The two-teeth clockwise milling cutter FRSTHW 19x30x12z2 (Aparathea Ltd., Brno, Czech Republic) with diameter D of 19 mm was used for experiments. Cutter inserts made of sintered carbide K10, HW 29.5x12x1.5 4S T04F were used at the cutter (Fig. 3). The cutting tool geometry: rake angle γ of 15° and clearance angle α of 20°.

Fig. 3. Milling cutter HW 19 x 30

Sintered carbide (SC) inserts were clamped into the milling cutter and secured with a bolt. The carbide inserts were identified by a letter with the appropriate symbol-letter to distinguish use in the machining of individual samples and for the uniqueness of the individual measurements. The number denoted a particular cutting inserts had the lower letter case a / b to distinguish the blade side. Cutting inserts marked U1 to U4 Fig. 4 were used for cutting the laminated particle board.

Fig. 4. SC cutting inserts HW 29.5x12x1.5 4S T04F

Machine Tool

The selected materials were machined on a three axis milling CNC machine SCM Tech 99 (Rimini, Italy) with the following parameters: working dimensions X, 3119 mm, Y, 1012 mm, Z, 100 mm; motor power, 6.6 kW, and maximum rotational speed of 1800 rpm. The two-teeth clockwise milling cutter was clamped in the milling CNC machine.

Methods

Cutting conditions

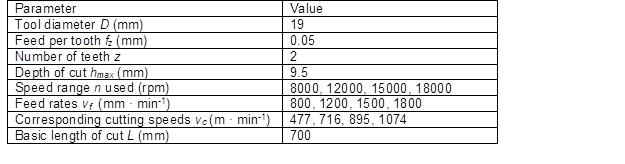

A climb milling was selected for machining. The range of minimum 4000 rpm and a maximum 18000 rpm were determined for a constant feed on the tooth (fz = 0.05 mm) and a constant width of cut ap = 18 mm (material thickness). Cutting and feed rate values are based on the relationship between tooth feed value, cutting speed, tool speed, and cutter diameter. All variables are defined in Table 1. The cutting speed (vc) was determined by Eqs. 1 and 2.

(1)

(2)

The feed rate vf was calculated by Eq. 3.

(3)

Table 1. Process Conditions of Cutting for Experiments

The tool life of the cutting edge is most affected by the cutting speed vc. Experimental determination of the tool life dependence on the cutting speed, i.e., T = fn (vc), was carried out using several cutting speeds. It was necessary to ensure that other working conditions were constant. The wear on the tool was represented by the wear curves for individual cutting speeds in the diagram KR = fn (T) for radial wear. Measurement of flank wear VB mainly used in metal cutting could not be used due to the difficulty measuring any changes during the experiments.Tool wear

To measure the radial wear of the KR tool, which is defined by the dependence KR = fn (T), it was necessary to calculate the time according to the following equation,

(4)

where T is the cutting time (min), L=700 is the length of workpiece (mm), and vf is the feed rate (mm ∙ min-1). The tool wear criterion was determined as KR = 10 µm.

Fig. 5. The comparison measurement instrument

Measuring equipment

To measure the tool wear, a digital dial gauge (KINEX 0-12.7 / 0.001, Prague, Czech Republic) was fixed on a measurement jig that was developed for the experiments see Fig. 5. The instrument measures deviations from the set dimension. First, it was necessary to calibrate the instrument according to the new tool inserts. The device used had measurement accuracy of 1 µm and maximum touch stroke of 12.7 mm.

Evaluation of measured values

Minitab® 15 statistical software (State College, PA, USA) was used to evaluate the measured values from experiments.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Radial Wear vs. Time

The radial wear KR of the cutting tool is time dependent.

Fig. 6. Tool wear of a cutting insert (red colored mark)

At time intervals that are given by the time of cutting, KR wear measurement has been performed. The results are further elaborated in time dependence graphs. The tool wear of inserts is shown using red colored mark in Fig. 6.

The resulting dependencies of the tool wear KR = fn (T), taken from the linear part wear that are highlighted in gray in tables, are attached to the tables of measurement in Figs. 7 to 10.

Table 2. Measurement of Tool Wear vs. Time, Inserts U1a / U2a, Speed vc1 = 477 m/min

Table 3. Measurement of Tool Wear vs. Time, Inserts U1b / U2b, Speed vc2 = 716 m/min.

Fig. 7. The regression of linear wear for vc1 = 477 m/min, KR [µm] and T [min]

Fig. 8. The regression of linear wear for vc2 = 716 m/min, KR [µm] and T [min]

Table 4. Measurement of Tool Wear vs. Time, Inserts U3a / U4a, Speed vc3 = 895 m/min

Fig. 9. The regression of linear wear for vc3 = 895 m/min, KR [µm] and T [min]

Table 5. Measurement of Tool Wear vs. Time, Inserts U3b / U4b, Speed vc4 = 1074 m/min

Fig. 10. The regression of linear wear for vc4 = 1074 m/min, KR [µm] and T [min]

The relationship between tool life T and cutting speed vc is as follows:

T . vcm = const. (5)

Here, the Taylor’s equation replaces the exponent m = 1/n. A wear rate of 10 μm from the original value of the cutting edge was determined as a criterion to state the tool life for that rate. To determine the dependence of tool life on cutting speeds, the T and vc values for the tool wear criterion were used into graphic representation log (T) = fn (log vc) (see Table 6). The statistical method of linear regression was then applied for solution. Confidence intervals (95%) of the measured data T = fn (vc) graphs for laminate particle board materials were processed. Results are shown in Fig. 11.

Table 6. Cutting Speeds and Corresponding Tool Life T1-T4 for KR = 10 μm

Fig. 11. Regression of T = fn (vc) with a confidence interval 95%

Equation 5 corresponding to the function from the graphic representation in Fig. 11 is then in final formula (Eq. 6).

T vc 2.082 = 252.35 x 105 or vc T 0.48 = 3590.7 (6)

CONCLUSIONS

- The wear mechanism of the particle board is different from the wear mechanism with abrasive particles that are characteristic of metals with abrasive particles. Darmawan at al. (2001, 2012) used the measurement of the wear on the clearance face.

- In the article, the comparative digital gauge used the measurement of radial wear KR that corresponds to cutting tool recession been used during the experiments. The course of the wear of wood-based materials exhibited similarity of the graphical representation with abrasive material cutting.

- The final dependence T = fn (vc) for machining the laminated particle board to select the proper cutting rate for a given tool life was determined. The final equation may be used for calculation of cutting rate/tool life according to operator demands.

- The criterion for determining tool life been selected in the linear part of wear curve to get proper and accurate results with the use of linear regression

- The experiments were evaluated using regression analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors greatly acknowledge the financial support provided by The Science Fund 2016, Brno University of Technology, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering FV 16-28 and the grant “Research of modern production technologies for specific applications,” reg. no. FSI-S-16-3717 and the project VEGA 1/0642/18: “Analysis of impacts of constructional parts of forest mechanisms in forestry environment regarding to energetic and ecological demands.”

REFERENCES CITED

Csanády, E., and Magoss, E. (2012). “Mechanics of Wood Machining”(2nd Ed.), Springer, New York, NY.

Darmawan, W., Tanaka C., Usuki H., and Ohtani T. (2001). “Performance of coated carbide tools in turning wood-based materials: Effect of cutting speeds and coating materials on the wear characteristics of coated carbide tools in turning wood-chip cement board,” Wood Science 47(5), 342-349.

Darmawan, W., Rahayu, I., Nandika, D., and Marchal, R. (2012). “The importance of extractives and abrasives in wood materials on the wearing of wood cutting tools,” BioResources7(4), 4715-4729. DOI: 10.15376/biores.11.4.4715-4729

Gaff, M., Sarvašová-Kvietková, M., Gašparík, M., and Slávik, M. (2016). “Dependence of roughness change and crack formation on parameters of wood surface embossing” Wood Research 61(1), 163-174.

Kučerová, V., Lagaňa, R., Výbohová, E., and Hýrošová, T. (2016). “The effect of chemical changes during heat treatment on the color and mechanical properties of fir wood,” BioResources 11(4), 9079-9094. DOI: 10.15376/biores.11.4. 9079-9094

Kvietková, M., Gaff, M., and Gašparík, M. (2015a). “Effect of thermal treatment on surface quality of beech wood after plane milling,” BioResources 10(3), 4226-4238. DOI: 10.15376/biores.10.3. 4226-4238

Kvietková, M., Gaff, M., Gašparík, M., Kaplan, L., and Barcík, Š. (2015b). “Surface quality of milled birch wood after thermal treatment at various temperatures,” BioResources 10(4), 6512-6521. DOI: 10.15376/biores.10.4. 6512-6521

Kvietková, M., Gaff, M., Gašparík, M., Kminiak, R., and Kris, A. (2015c). “Effect of number of saw blade teeth on noise level and wear of blade edges during cutting of wood,” BioResources 10(1), 1657-1666. DOI: 10.15376/biores.10.1.1657-1666

Mazáň, A., Vančo, M., and Barcík, S. (2017). “Influence of technological parameters on tool durability during machining of juvenile wood,” BioResources 12(2), 2367-2378. DOI: 10.15376/biores.12.2. 2367-2378

Šebelová, E. and Chladil, J. (2013). “Tool wear and machinability of wood-based materials during machining process,” Manufacturing Technology 13(2), 231-236.

Sedlecký, M., and Sarvašová Kvietková, M. (2017). “Surface waviness of medium-density fibreboard (MDF) and edge-glued panel EGP after edge milling,” Wood Research 62(3), 459-470.

Shaw, M. C. (2005). “Metal Cutting Principles” (2nd Ed.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Thoemen, H., Irle, M., and Sernek, M. (2010). Wood-based Panels – An Introduction for Specialists, Brunel University Press, London.

Submitted: December 12, 2018; Peer review completed: February 17, 2019; Revised version received and accepted; March 5, 2019; Published: March 8, 2019.

DOI: 10.15376/biores.14.2.3495-3505